Mutually protected occlusion

Mutually protected occlusion is also known as canine-protected occlusion or organic occlusion . It had its origin in the work of D’Amico, 48Stuart, 49 , 50Stallard and Stuart, 27and Lucia 51and the members of the Gnathological Society. They observed that in many mouths with a healthy periodontium and minimum wear, the teeth were arranged so that the overlap of the anterior teeth prevented the posterior teeth from making any contact on either the working or the nonworking side during mandibular excursions. This separation from occlusion was termed disocclusion . According to this concept of occlusion, the anterior teeth bear the entire load, and the posterior teeth are disoccluded in any excursive position of the mandible. The desired result is an absence of frictional wear.

The position of maximal intercuspation coincides with the optimal condylar position of the mandible. All posterior teeth are in contact with the forces being directed along their long axes. The anterior teeth either contact lightly or are very slightly out of contact (approximately 25 microns), relieving them of the obliquely directed forces that would be the result of anterior tooth contact. As a result of the anterior teeth protecting the posterior teeth in all mandibular excursions and the posterior teeth protecting the anterior teeth at the intercuspal position, this type of occlusion came to be known as a mutually protected occlusion . This arrangement of the occlusion is probably the most widely accepted because of its ease of fabrication and greater tolerance by patients.

However, to reconstruct a mouth with a mutually protected occlusion, it is necessary to have anterior teeth that are periodontally healthy. In the presence of anterior bone loss or missing canines, the mouth should probably be restored to group function (unilateral balance). The added support of the posterior teeth on the working side will distribute the load that the anterior teeth may not be able to bear. The use of a mutually protected occlusion is also dependent on the orthodontic relationship of the opposing arches. In either a Class II or a Class III malocclusion (Angle), the mandible cannot be guided by the anterior teeth. A mutually protected occlusion cannot be used in a situation of reverse occlusion, or crossbite, in which the maxillary and mandibular facial cusps interfere with each other in a working-side excursion.

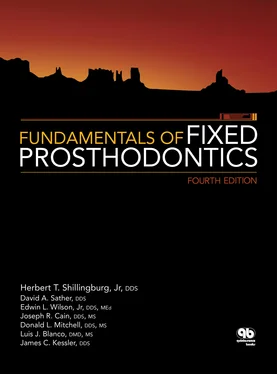

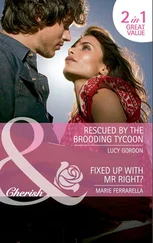

Fig 2-16A shallow protrusive condylar inclination requires short cusps (a) , while a steeper path permits the cusps to be longer (b) .

Effects of Anatomical Determinants

The anatomical determinants of mandibular movement (ie, condylar and anterior guidance) have a strong influence on the occlusal surface morphology of the teeth being restored. There is a relationship between the numerous factors, such as immediate lateral translation, condylar inclination, and even disc flexibility, on the cusp height, cusp location, and groove direction that are acceptable in the restoration. It is beyond the scope of this text to discuss all of the nearly 50 rules that have been written on the subject of determinants 52; therefore, only those that have the greatest effect on morphology are considered.

When subjects with normal occlusions perform repeated lateral mandibular movements, they will not trace the same path on electronic recordings, presumably because of the flexible nature of the articular disc. The measured deviation averages 0.2 mm in centric relation, 0.3 mm in working movements, and 0.8 mm in both protrusive and nonworking movements. 53To avoid occlusal interferences and nonaxially directed forces on molars during eccentric mandibular movements, molar disocclusion must equal or surpass these observed deviations in mandibular movement.

Healthy natural occlusions exhibit clearances that will accommodate these aberrations. Measurements of disocclusions from the mesiofacial cusp tips of mandibular first molars in asymptomatic test subjects with good occlusions showed separations averaging 0.5 mm in working, 1.0 mm in nonworking, and 1.1 mm in protrusive movements. 54Therefore, one of the treatment goals in placing occlusal restorations should be to produce a posterior occlusion with buffer space that equals or surpasses the deviations resulting from natural variations found in the TMJ.

Chief among those aspects of condylar guidance that will have an impact on the occlusal surface of posterior teeth are the protrusive condylar path inclination and mandibular lateral translation.

The inclination of the condylar path during protrusive movement can vary from steep to shallow in different patients. It forms an average angle of 30.4 degrees with the horizontal reference plane (43 mm above the maxillary central incisor edge). 17,18If the protrusive inclination is steep, the cusp height may be longer. However, if the inclination is shallow, the cusp height must be shorter ( Fig 2-16).

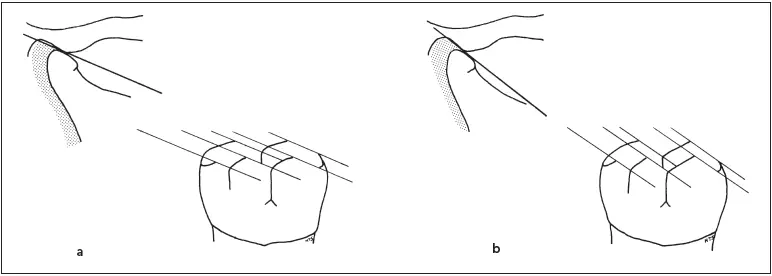

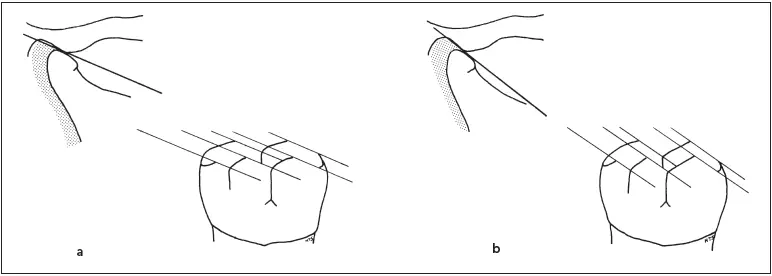

Immediate mandibular lateral translation is the lateral shift during initial lateral movement. If immediate lateral translation is great, then the cusp height must be shorter or the fossa width wider ( Fig 2-17). With minimal immediate translation, the cusp height may be made longer or the fossa may be narrower.

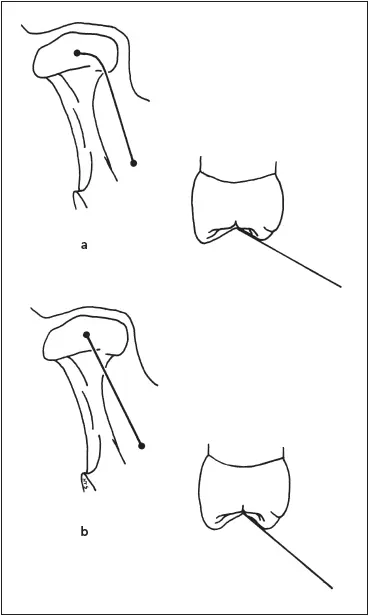

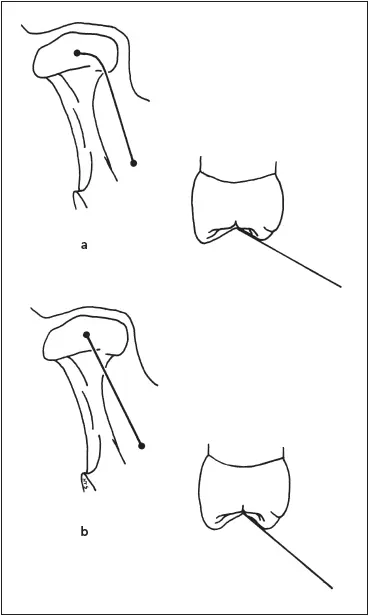

Ridge and groove directions are affected by the condylar path, particularly the lateral translation. The effects are observed on the occlusal surface of a mandibular molar and premolar with the paths traced by the palatal cusps of the respective opposing maxillary teeth. The working path is traced on the mandibular tooth in a lingual direction, and the nonworking path is in a distofacial direction. The nearer the tooth is to the working-side condyle anteroposteriorly, the smaller the angle between the working and nonworking paths ( Fig 2-18). The farther the tooth is located from the working-side condyle, the greater the angle between the working and nonworking condyles. When immediate lateral translation is increased, the angle also becomes more oblique.

Fig 2-17A pronounced immediate lateral translation requires that the cusps be short or the fossa wider (a), while a gradual lateral translation allows the cusps to be longer or the fossa narrower (b).

Fig 2-18The angle between the working (W) and nonworking (NW) paths is greater on teeth located farther from the condyle.

During protrusive movement of the mandible, the incisal edges of mandibular anterior teeth move forward and downward along the palatal concavities of the maxillary anterior teeth. The track of the incisal edges from maximal intercuspation to edge-to-edge occlusion is termed the protrusive incisal path. The angle formed by the protrusive incisal path and the horizontal reference plane is the protrusive incisal path inclination, which ranges from 50 to 70 degrees. 55,56Although they are conventionally regarded as independent factors, there is evidence to suggest that condylar inclination and anterior guidance are linked, or dependent factors 57,58(Takayama H and Hobo S, unpublished data, 1989). In a healthy occlusion, the anterior guidance is approximately 5 to 10 degrees steeper than the condylar path in the sagittal plane. Therefore, when the mandible moves protrusively, the anterior teeth guide the mandible downward to create disocclusion, or separation, between the maxillary and mandibular posterior teeth. The same phenomenon should occur during lateral mandibular excursions.

Читать дальше