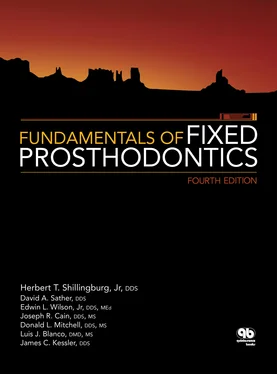

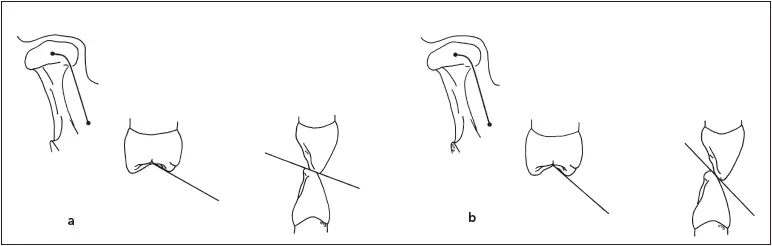

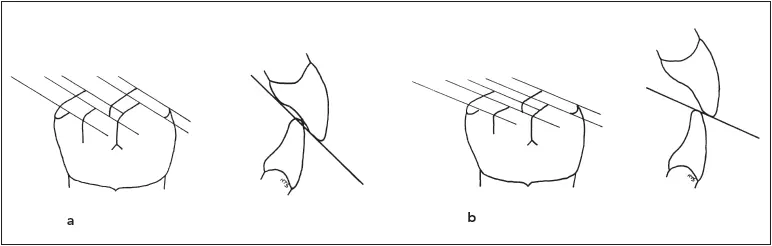

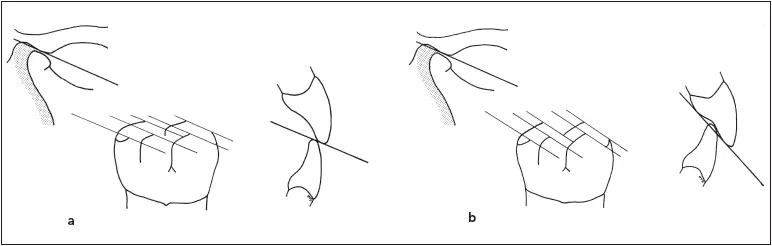

Fig 2-19 (a) A pronounced vertical overlap of the anterior teeth permits posterior teeth to have longer cusps. (b) A minimum anterior vertical overlap requires shorter cusps.

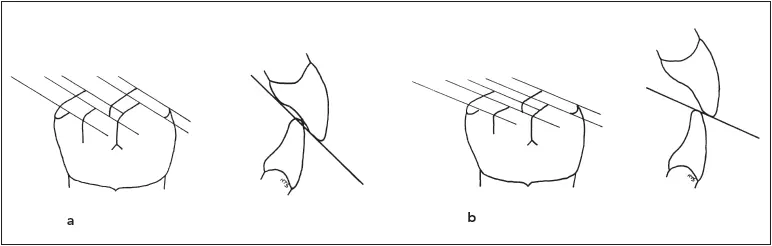

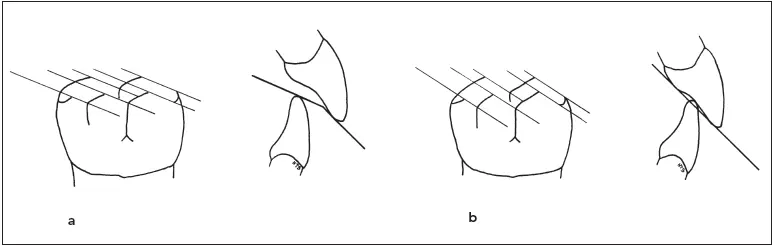

Fig 2-20 (a) A pronounced horizontal overlap of the anterior teeth requires short cusps on the posterior teeth. (b) A minimum anterior horizontal overlap permits the posterior cusps to be longer

The palatal surface of a maxillary anterior tooth has both a concave aspect and a convexity, or cingulum. The mandibular incisal edges should contact the maxillary palatal surfaces at the transition from the concavity to the convexity in the centric relation position. The concavity represents a uniform shape in all subjects. 59

Anterior guidance, which is linked to the combination of vertical and horizontal overlap of the anterior teeth, can affect occlusal surface morphology of the posterior teeth. The greater the vertical overlap of the anterior teeth, the longer the posterior cusp height may be. When the vertical overlap is less, the posterior cusp height must be shorter ( Fig 2-19). The greater the horizontal overlap of the anterior teeth, the shorter the cusp height must be. With a decreased horizontal overlap, the posterior cusp height may be longer ( Fig 2-20).

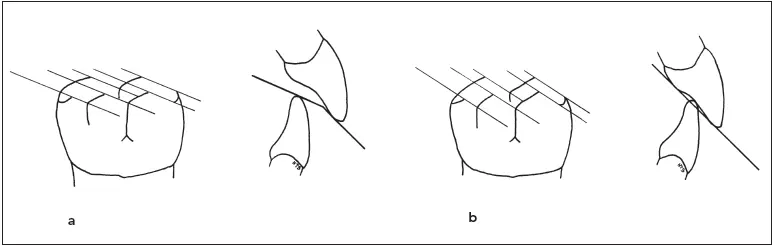

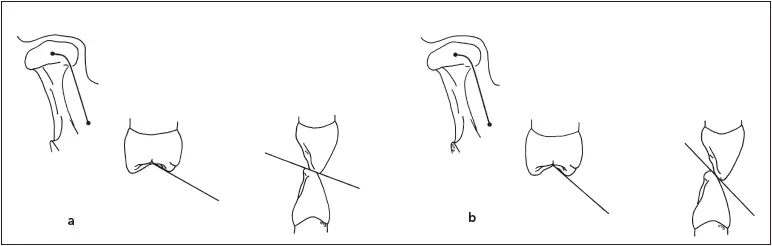

Fig 2-21While a shallow protrusive path would require short cusps in the presence of minimal anterior guidance (a) , the posterior cusps can be lengthened if the anterior guidance is increased (b) .

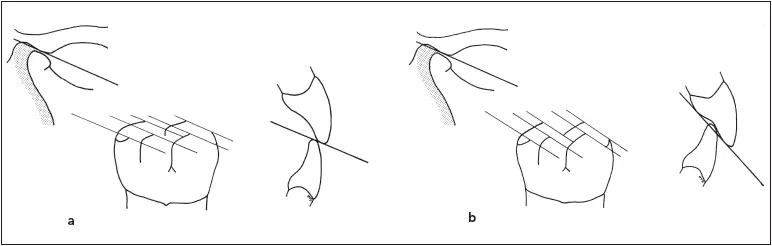

Fig 2-22 (a) A pronounced immediate lateral translation would dictate short cusps where there is little anterior guidance. (b) However, the cusps can be lengthened if the anterior guidance is increased.

By increasing anterior guidance to compensate for inadequate condylar guidance, it is possible to increase the cusp height. If the protrusive condylar inclination is shallow, requiring short posterior cusps, the cusps may be lengthened by making the anterior guidance steeper ( Fig 2-21). In like manner, increasing anterior guidance will permit the lengthening of cusps that would otherwise have to be shorter in the presence of a pronounced immediate lateral translation ( Fig 2-22).

1. Nomenclature Committee of the Academy of Denture Prosthetics. Glossary of Prosthodontic Terms, ed 5. St Louis: Mosby, 1987:15.

2. Okeson JP. Management of Temporomandibular Disorders and Occlusion, ed 6. St Louis: Mosby, 2008:96.

3. McCollum BB, Stuart CE. Gnathology—A Research Report. South Pasadena, CA: Scientific Press, 1955:91–123.

4. Lucia VO. Modern Gnathological Concepts. St Louis: Mosby, 1961:15–22.

5. Dawson PE. Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Occlusal Problems. St Louis: Mosby, 1974:293.

6. Kornfeld M. Mouth Rehabilitation: Clinical and Laboratory Procedures. St Louis: Mosby, 1967:34.

7. Bauer A, Gutowski A, Koehler HM. Gnathology: Introduction to Theory and Practice. Berlin: Quintessence, 1975:85–91.

8. Huffman R, Regenos J. Principles of Occlusion, ed 8. Columbus, OH: H & R Press, 1980:VA1–VB39.

9. Parsons MT, Boucher LJ. The bilaminar zone of the meniscus. J Dent Res 1966;45:59–61.

10. McNeill C. The optimum temporomandibular joint condyle position in clinical practice. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 1985;5(6):52–76.

11. Dawson PE. Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Occlusal Problems. St Louis: Mosby, 1961:48–79.

12. Brill N, Lammie GA, Osborne J, Perry HT. Mandibular positions and mandibular movements. Br Dent J 1959;106:391–400.

13. Kohno S. Analyse der Kondylenbewegung in der Sagittlebene. Dtsch Zahnärtzl Z 1974;27:739–743.

14. Bennett NG. A contribution to the study of the movements of the mandible. Proc Roy Soc Med 1908;1:79–95.

15. Aull AE. Condylar determinants of occlusal patterns. Part I. Statistical report on condylar path variations. J Prosthet Dent 1965;15:826–835.

16. Lundeen HC, Wirth CG. Condylar movement patterns engraved in plastic blocks. J Prosthet Dent 1973;30:866–875.

17. Hobo S, Mochizuki S. Study of mandibular movement by means of an electronic measuring system. Part I. J Jpn Prosthodont Soc 1982;26:619–634.

18. Hobo S, Mochizuki S. Study of mandibular movement by means of an electronic measuring system. Part II. J Jpn Prosthodont Soc 1982;26:635–653.

19. Nomenclature Committee of the Academy of Denture Prosthetics. Glossary of Prosthodontic Terms, ed 5. St Louis: Mosby, 1987:31.

20. Guichet NF. Occlusion. Anaheim, CA: Denar, 1970:13.

21. Manly RS, Pfaffmann C, Lathrop DD, Kayser J. Oral sensory thresholds of persons with natural and artificial dentitions. J Dent Res 1952;31:305.

22. Williamson EH, Lundquist DO. Anterior guidance: Its effect on electromyographic activity of the temporal and masseter muscles. J Prosthet Dent 1983;49:816–823.

23. Manns A, Chan C, Miralles R. Influence of group function and canine guidance or electromyographic activity of elevator muscles. J Prosthet Dent 1987;57:494–501.

24. Dawson PE. Temporomandibular joint pain-dysfunction problems can be solved. J Prosthet Dent 1973;29:100–112.

25. Dawson PE. Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Occlusal Problems. St Louis: Mosby, 1961:299.

26. Ramfjord SP. Dysfunctional temporomandibular joint and muscle pain. J Prosthet Dent 1961;11:353–374.

27. Stallard H, Stuart CE. Eliminating tooth guidance in natural dentitions. J Prosthet Dent 1961;11:474–479.

28. Schuyler CH. Factors contributing to traumatic occlusion. J Prosthet Dent 1961;11:708–715.

29. Yuodelis RA, Mann WV Jr. The prevalence and possible role of nonworking contacts in periodontal disease. Periodontics 1965;3:219–223.

30. Whitsett LD, Shillingburg HT Jr, Duncanson MG Jr. The nonworking interference. Your Okla Dent Assoc J 1974;65:5–7,11.

31. Posselt U. Studies in the mobility of the human mandible. Acta Odontol Scand 1952;10(suppl 10):1–109.

32. Ramfjord SP, Ash MM Jr. Occlusion, ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1971:104.

33. Schiffman EL, Fricton JR, Haley D. The relationship of occlusion, parafunctional habits and recent life events to mandibular dysfunction in a non-patient population. J Oral Rehabil 1992;19:201–223.

34. Rugh JD, Solberg WK. Electromyographic studies of bruxist behavior before and during treatment. J Calif Dent Assoc 1975;3:56–59.

35. Solberg WK, Clark GT, Rugh JD. Nocturnal electromyographic evaluation of bruxism patients undergoing short term splint therapy. J Oral Rehabil 1975;2:215–223.

36. Clark GT, Beemsterboer PL, Solberg WK, Rugh JD. Nocturnal electromyographic evaluation of myofascial pain dysfunction in patients undergoing occlusal splint therapy. J Am Dent Assoc 1979;99:607–611.

37. Yemm R. Cause and effect of hyperactivity of the jaw muscles. In: Bryant P, Gale E, Rugh J (eds). Oral Motor Behavior: Impact on Oral Conditions and Dental Treatment, NIH Publication 79- 1845. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, 1979.

Читать дальше