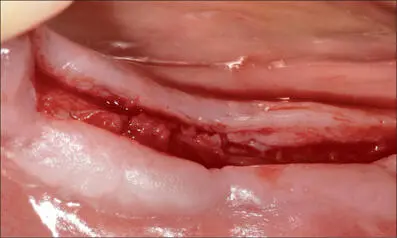

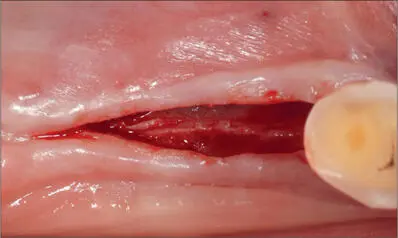

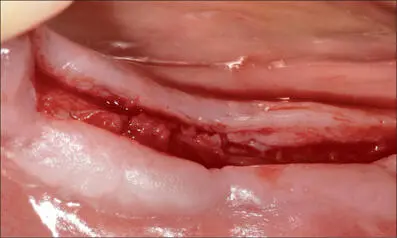

Fig 6i Early healing (at six weeks). A new mucogingival line is already evident.

Fig 6j Fifteen months after implant placement, facial view. Ideal contour of the soft tissues thanks to bone grafting and papilla rotation at the time of implant placement.

In many circumstances, poor implant placement may result in restricted access for proper oral hygiene and increase the risk of mucosal inflammation. Plaque accumulation at implant sites causes a more pronounced inflammatory response compared to natural teeth (Berglundh and coworkers 2011). Indeed, even though the evidence is limited, there is a strong common perception that properly placed implants do not present biological complications as frequently as poorly placed implants.

Apart from the prosthetically driven position, a wide band of non-mobile, keratinized mucosa, a correct peri-implant sulcus, and a thick tissue phenotype might seem desirable, if not essential, for reducing the incidence of tissue inflammation and long-term complications around implants.

3.2 Soft-Tissue Management Before Implant Placement

On the occasion of the 2017 World Workshop, Hämmerle and Tarnow (2018) reported that a significant amount of controlled prospective studies with medium-size patient samples indicated that thin soft tissue around implants leads to increased peri-implant marginal bone loss compared to thick soft tissue. Most of the data, however, were published by one group of researchers.

Linkevicius and coworkers (2009) placed 46 implants in 19 patients. The implants were divided into two groups related to soft-tissue thickness. At the one-year follow-up, the marginal bone loss at the implants in the thin-tissue group was on the order of 1.5 mm, compared to only 0.3 mm in the thick-tissue group.

In addition, the same investigators analyzed the effects of buccal soft-tissue thickness on marginal bone-level changes in 32 patients. They found a significant correlation between soft-tissue thickness and bone loss, with thin soft-tissue sites presenting more bone loss (0.3 mm versus 0.1 mm) at the one-year follow-up.

That thin soft tissue leads to increased marginal bone loss was confirmed in another recent study (Linkevicius and coworkers 2015). In addition to the thin-tissue and thick-tissue groups, the investigators followed a third group of about 30 patients whose thin soft tissue was augmented by grafting at the time of implant. The resulting bone loss was not different from that in thick soft-tissue group. These findings seem to indicate that adequate soft-tissue thickness benefits the stability of the peri-implant bone levels.

In another study, Puisys and Linkevicius (2015) concluded that, since significantly less bone loss can occur in naturally thick soft tissue than in patients with a thin tissue phenotype, augmenting the tissue could be the way to reduce crestal bone loss.

Based on the observation that significantly less bone loss occurs around implants placed in thick tissue phenotypes compared to thin phenotypes, clinicians may be encouraged to augment thin soft tissue before or during implant placement in order to facilitate crestal bone stability. Figures 7a-ishow an example of this treatment approach in the posterior mandible of a 63-year-old woman.

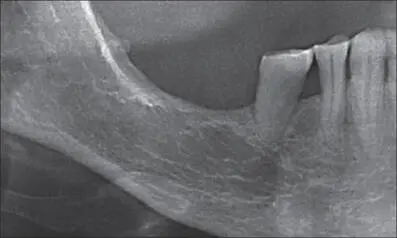

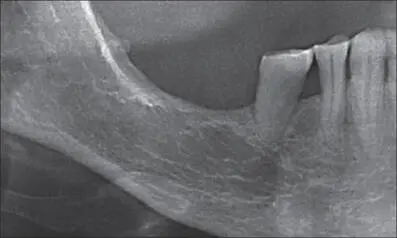

Fig 7a Panoramic radiograph of the edentulous sites 46 and 47. There is barely enough bone available for implant placement above the mandibular canal.

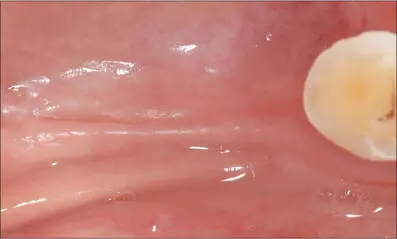

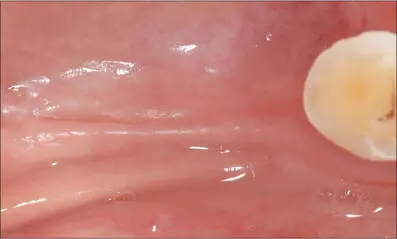

Fig 7b Edentulous area, buccal view. Very shallow vestibule and absence of keratinized mucosa.

Fig 7c Edentulous area, occlusal view. Very thin crest.

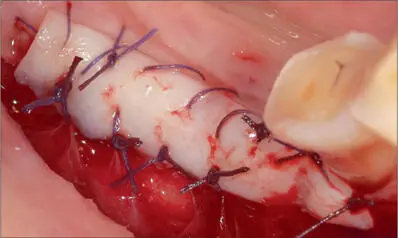

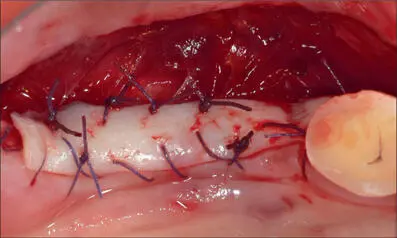

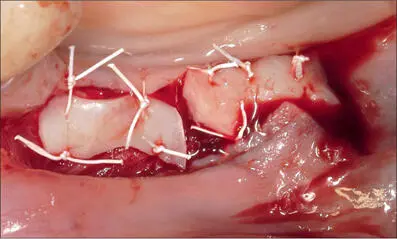

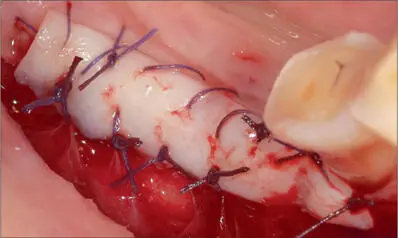

Fig 7d Free gingival graft harvested from the palate sutured above a split-thickness flap in the area where the implants are planned.

Fig 7e Graft sutured with 4-0 Vicryl, occlusal view

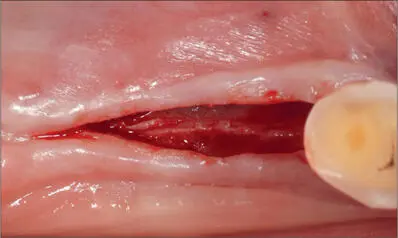

Fig 7f At three months, a full-thickness flap was raised lingually and buccally for placing the implants. Thicker keratinized tissue on both sides of the flap.

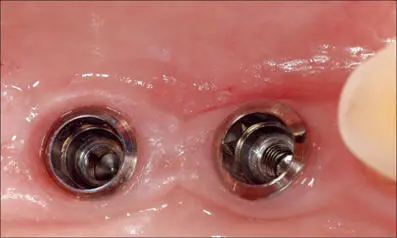

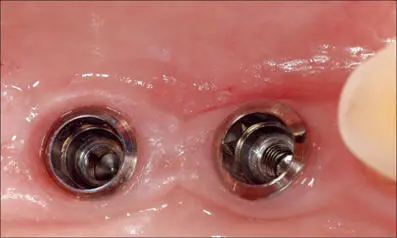

Fig 7g At the time of the final impression, occlusal view. Both implants are surrounded by a thick collar of keratinized tissue, that creates an effective barrier that protects the peri-implant structures.

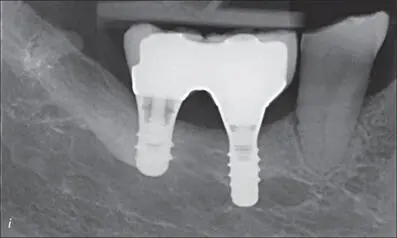

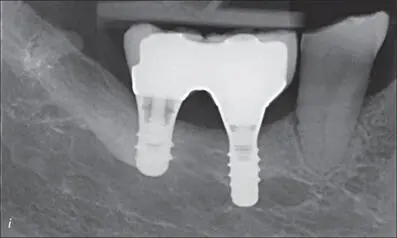

Figs 7h-i Clinical and radiographic views of the screw-retained ceramic crowns at 6 years. Prosthetic procedures: Dr. Nicola Scotti – Torino, Italy

From a clinical perspective, the presence of a wide band of keratinized tissue facilitates the transmucosal healing of dental implants, even in cases where bone regeneration is required, as it allows the creation of a thick soft-tissue cuff around the collar of the implant. Figures 8a-lshow an example of this treatment approach in the posterior mandible of a 57-year-old woman, for whom horizontal bone regeneration was needed in conjunction with implant placement.

Fig 8a Preoperative view. Bone atrophy associated with the presence of very thin mucosa, with almost no keratinization.

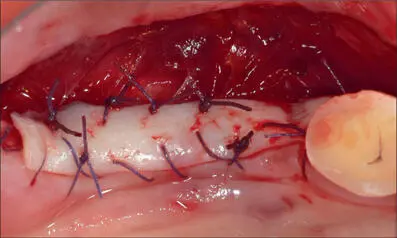

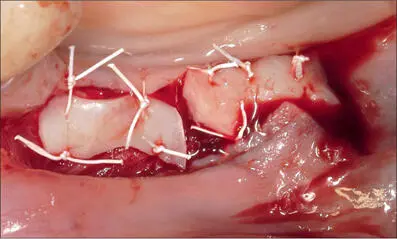

Fig 8b Two free gingival grafts sutured in the area where implant placement and bone regeneration was planned.

Fig 8c Three months after soft-tissue augmentation. A thick band of keratinized tissue was present on the lingual and buccal aspects of the full-thickness flap.

Читать дальше