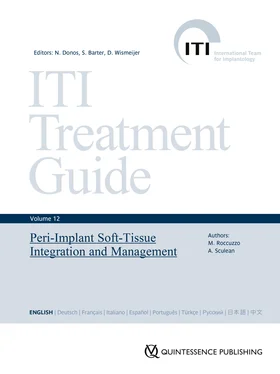

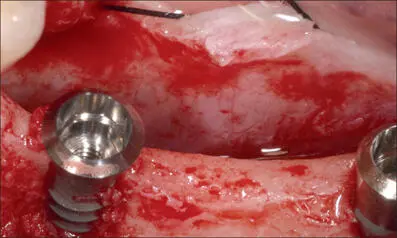

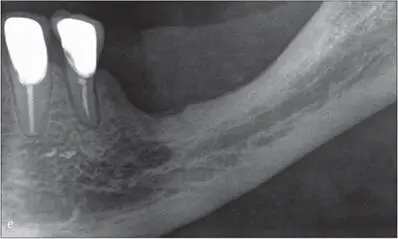

Fig 8d Implants at sites 35 and 37 (S, RN, diameter 3.3 mm, length 10 mm, and S, RN, diameter 4.8 mm, length 10 mm; Institut Straumann AG) with a large dehiscence-type bone defect on the buccal aspect.

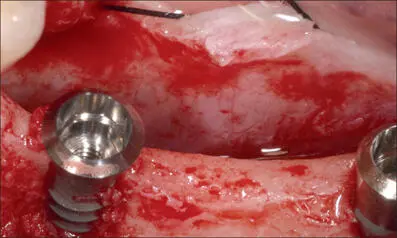

Fig 8e Guided bone regeneration with autologous bone in contact with the implant surface, followed by a layer of deproteinized bovine bone mineral (DBBM). Resorbable collagen membrane adapted around the implants to stabilize the graft.

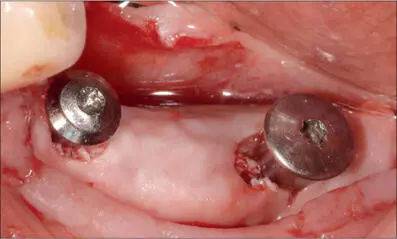

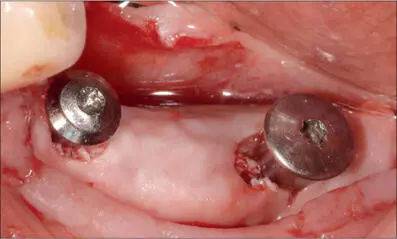

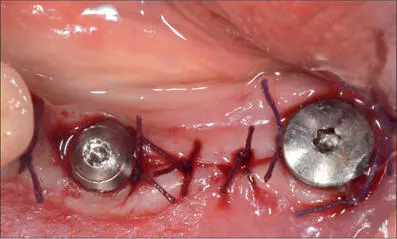

Fig 8f Sutures for transmucosal healing. Ideal soft-tissue seal around the collar of the implants thanks to the preliminary soft-tissue augmentation.

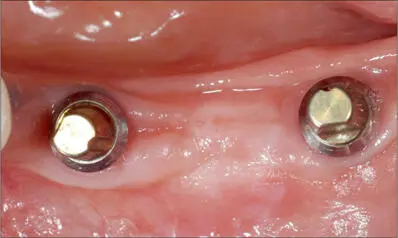

Fig 8g At the time of delivery of the final prosthesis, occlusal view.

Fig 8h Three-unit ceramic bridge delivered and secured with temporary cement.

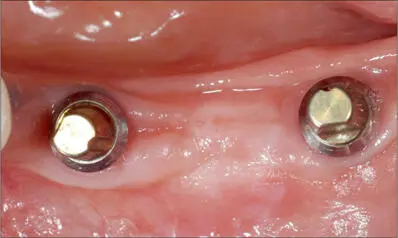

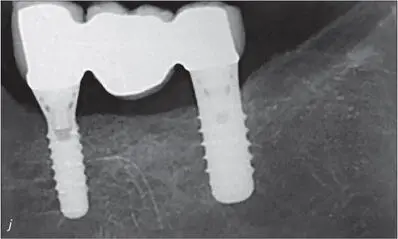

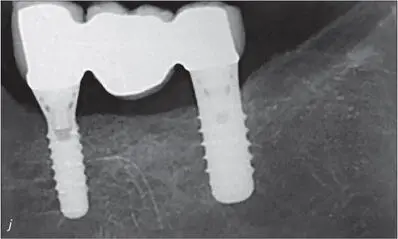

Figs 8i-j One-year clinical and radiographic follow-up. The prosthesis was removed to double-check the condition of the soft tissues and later then reinserted using definitive cement.

Figs 8k-l Ten-year follow-up. Minor pigmentation of the ceramic crown on the buccal side. Healthy peri-implant soft tissue with minimal probing depth.

Several studies have argued the use of various techniques for vertical ridge augmentation in cases of severe atrophy of the alveolar ridge, using either non-resorbable or resorbable membranes supported by a space-making device or a titanium mesh (Esposito and coworkers 2008; Fontana and coworkers 2011; Roccuzzo and coworkers 2017a).

All these studies also showed that the use of a barrier device is a technique-sensitive procedure and subject to surgical complications (Jepsen and coworkers 2019). One of the main reasons for GBR failures is related to exposure of the barrier membrane, leading to bacterial contamination of the surgical area and infection and thereby compromising the regeneration outcome (Sanz and coworkers 2019). Even though there have been no specific studies on this matter, it might be suggested that membrane exposure, especially during the first four weeks postoperatively, may be higher in patients with very thin mucosa, or without keratinization, or with scar tissue. In specific circumstances, it is therefore reasonable to consider optimizing the quantity and quality of the soft tissue before hard-tissue regenerative procedures are carried out.

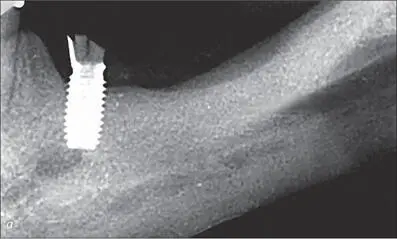

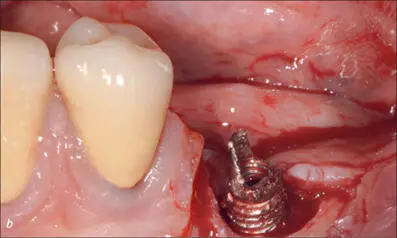

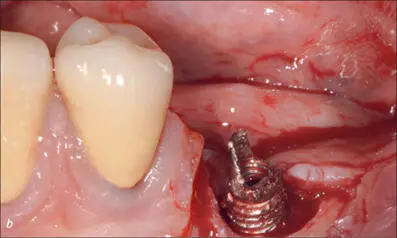

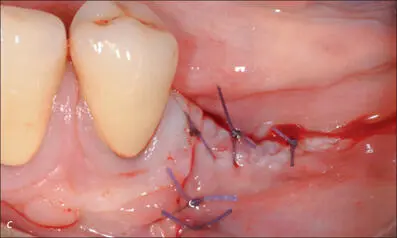

Figures 9a-pexemplify this approach in the mandible of a 63-year-old patient, a dentist and current cigarette smoker. He had previously received an implant at site 35, but it had recently fractured. After surgically removing the fractured implant, vertical bone augmentation was required, as the bone was not high enough to place an implant above the mandibular canal. The examination of the local soft tissue revealed minimal keratinized mucosa and the presence of scar tissue as a result of previous surgery. To reduce the risk of soft-tissue dehiscence and of exposure or infection of the area following GBR, the patient was advised that preliminary soft-tissue augmentation was required prior to any attempt at vertical bone regeneration.

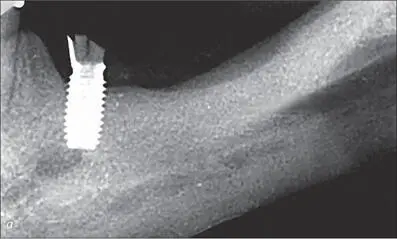

Figs 9a-c Surgical removal of the fractured implant.

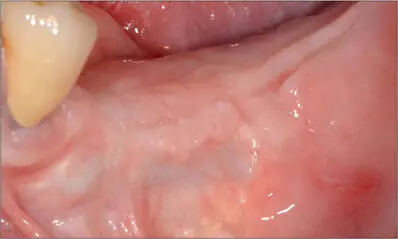

Figs 9d-e After three months, site 35 presented with minimal keratinized mucosa and scar tissue, considered not to be ideal in view of the planned vertical bone augmentation.

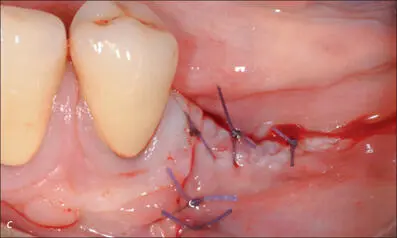

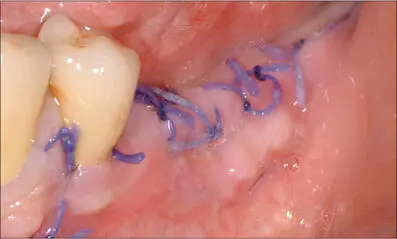

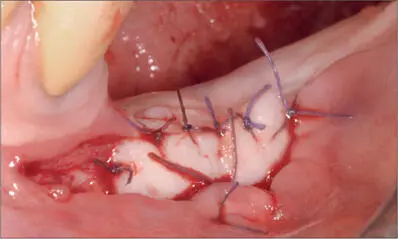

Fig 9f Free gingival graft sutured on the periosteum after elevating a split-thickness flap, with 4-0 Vicryl.

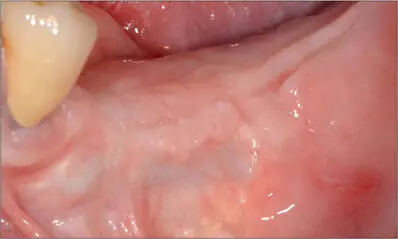

Fig 9g Four months after soft-tissue augmentation, lateral view.

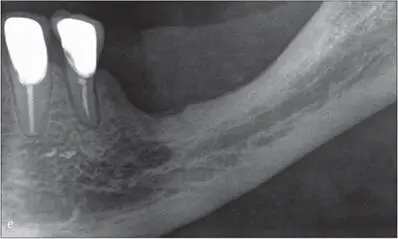

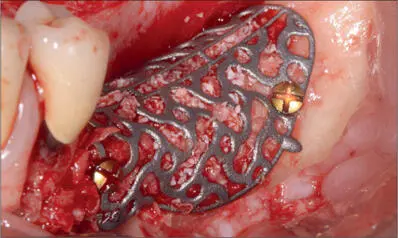

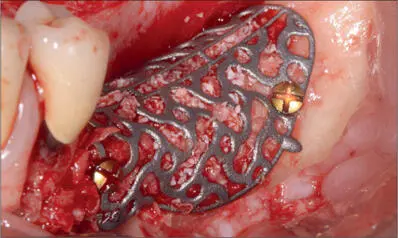

Fig 9h Custom-made Ti-mesh filled with autologous bone combined with DBBM and secured with two screws to contain and protect the bone graft. The presence of thick mucosa reduced the need for a collagen membrane.

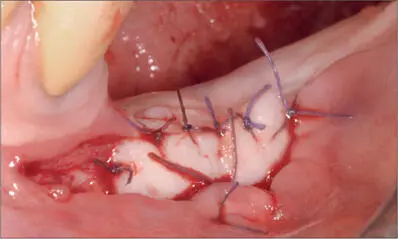

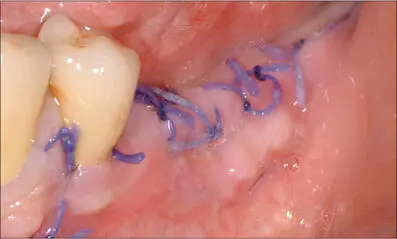

Fig 9i Flap closed without tension despite coronal advancement and adapted to completely cover the augmented area. The flap was stabilized with Vicryl 3-0 horizontal mattress sutures at the apical aspect and Vicryl 4-0 multiple single interrupted sutures at the far coronal aspect.

Fig 9j Two weeks after the surgery. The flap had healed well, and the sutures could be removed.

Fig 9k Clinical view six months after regeneration surgery. Optimal healing.

Читать дальше