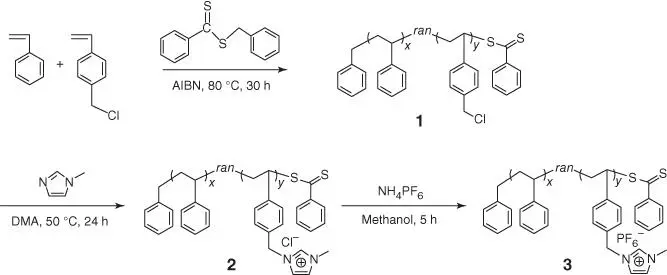

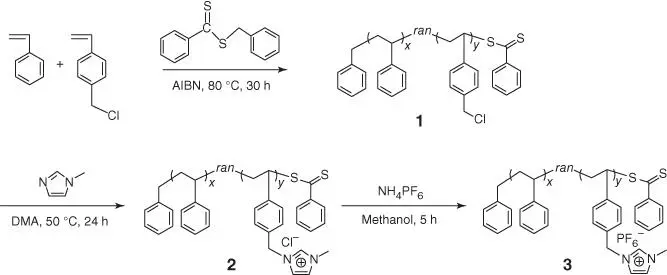

Figure 2.4 Synthetic routes for P[S‐r‐VBMI][PF 6].

Source: Seo and Moon [75].

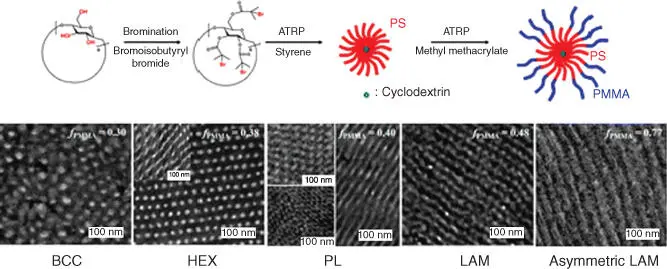

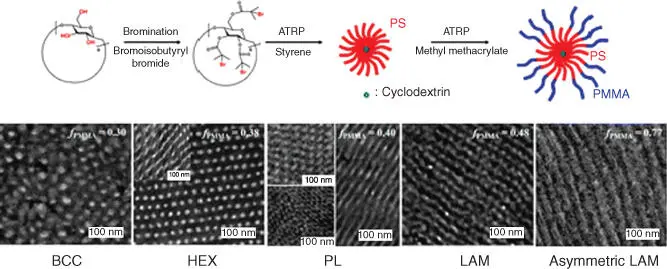

Figure 2.5 Synthetic routes for (PS‐b‐PMMA) 18.

Source: Jang et al. [77].

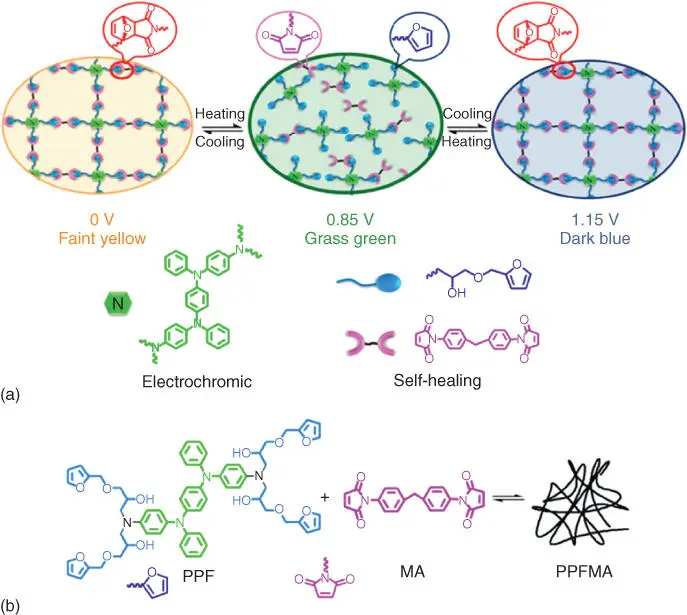

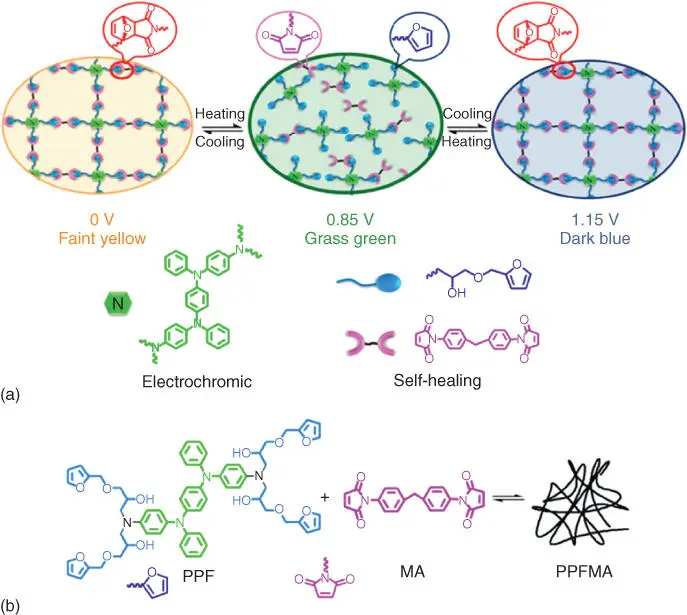

Figure 2.6 (a) The mechanism of self‐healing process for electrochromic PPFMA film and (b) the retro‐DA and DA reaction for self‐healing polymer PPFMA.

Source: Zheng et al. [84].

However, developing a material that simultaneously exhibits excellent EC properties and good self‐healing behavior at low temperature is still an unmet challenge, such as large optical contrast, high coloration efficiency, and long‐term, stability, and fast healing process.

2.3.3 Cross‐linking Polymer Electrolytes (CPEs)

The high ionic conductivity of PEs at low temperature is related to the amorphous nature of the polymer matrix ( Figure 2.7). The cross‐linked PEs show good ionic conductively and amorphous feature [85]. Cross‐linking was reported to improve the dimensional stability and increase the dynamic storage modulus of the PE. This technique was used to modify positively various PE properties [86, 87], while brittleness, low elasticity, and processability inevitably occur in cross‐linked polymer [88]. In the study of lithium salts‐based electrolytes, PEO, PMMA, PVC, etc. were commonly organized into cross‐linked PEs. Matsui et al. have prepared a cross‐linked PE of poly(ethylene oxide) 2‐(2‐methoxy ethoxy) ethyl glycidyl ether with and without allyl glycidyl ether P(ethylene oxide [EO]/2‐(2‐methoxyethoxy)ethyl glycidyl ether [MEEGE]/allyl glycidyl ether [AGE]) complexed in LiN(CF 3SO 3) 2salts [89]. Kuratomi et al. studied a cross‐linked copolymer of ethylene oxide and propylene oxide with LiBF 4or LiN(CF 3SO 2) 2salts [90]. The concentration and anions in lithium salts are key parameters in determining electrochemical performance. As was studied, good ionic conductivity and mechanical strength have been exhibited in a cross‐link of high molecular weight poly(oxy ethylene)s PEs [91]. Lee et al. have also reported a cross‐linked composite PE by polymerizing alkyl monomer and polyethylene glycol dimethylcrylate (PEGDMA) in LiPF 6/EC [92]. The studies indicate that ionic conductivity and flexibility of the PEs are dependent on the monomer content.

Figure 2.7 Pictorial model of a preparation of a cross‐linked polymer.

In fact, while many conventional ECDs using the EC media of cross‐linked polymer gels are exposed to the dynamic range of real‐world temperatures, cross‐linked polymer gels may not be optically viable for commercial use due to visual irregularities and/or defects. The patent in 2003 reported a self‐healing cross‐linked polymer gel electrolyte used as EC medium, which could solve these detriments and complications in ECDs [92].

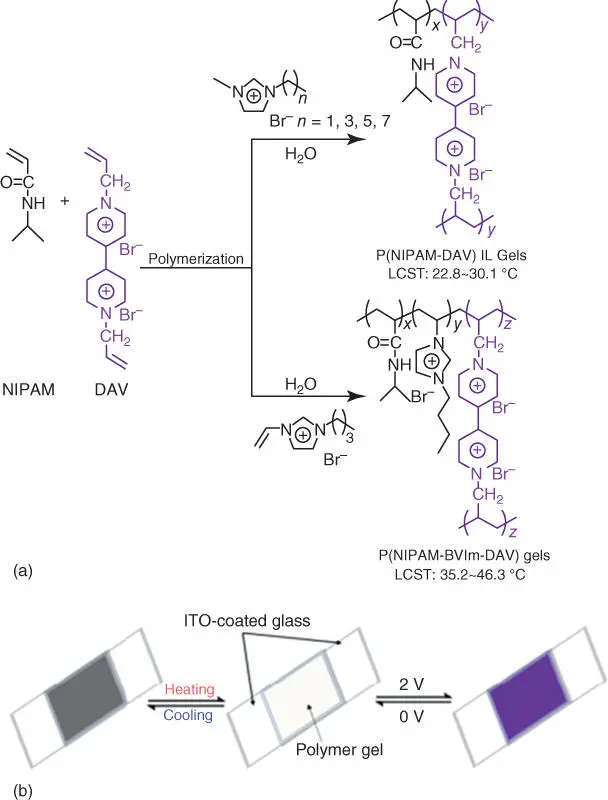

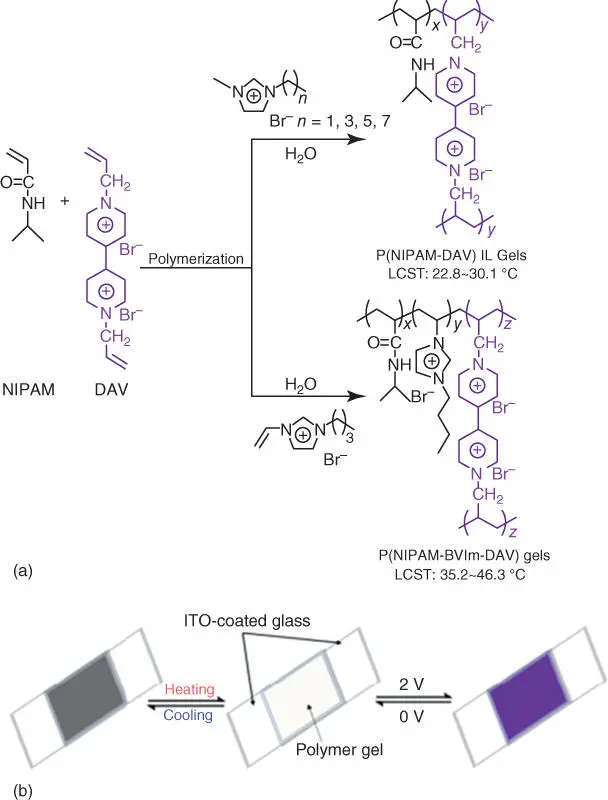

Another intriguing field for the possible application of ionic liquid polymers (ILPs) is using polymerized ionic liquids (PILs) in ECDs. Among different IL electrolytes, cross‐linked IL PEs have been explored recently. Yan and coworkers reported thermo‐ and electro‐dual responsive ILPs electrolytes, which were synthesized through the co‐polymerization of an ionic liquids monomer (ILM), 3‐butyl‐1‐vinyl‐imidazolium bromide ([BVIm][Br]) and N ‐isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM) using diallyl‐viologen as both the cross‐linking agent and the EC material, respectively ( Figure 2.8) [93]. The electro‐ and thermo‐responsive behaviors can be found simultaneously under electrical and temperature stimuli, which demonstrates the application of the dual‐response smart window [93].

Figure 2.8 (a) General synthetic routes for P(NIPAM‐fv [DAV]) IL gels and P(NIPAMBVIm‐DAV) gels and (b) a schematic mechanism of thermochromic and electrochromic devices based on the prepared polymer gels.

Source: Chen et al. [93].

2.3.4 Ceramic Polymer Electrolytes

Differing from liquid and gel electrolytes, salt in solid‐like PEs is dissolved directly into the solid medium. It is usually a relatively high dielectric constant polymer (PEO, PMMA, PAN, polyphosphazenes, siloxanes, etc.) and a salt with low lattice energy.

Multiple advantages of using solid PEs in electrochemical cells are as follows:

1 (1) Non‐volatility.

2 (2) No decomposition at the electrodes.

3 (3) No possibility of leaks.

4 (4) Decreased cell price (such as PEO, PMMA, etc.).

5 (5) Flexibility.

6 (6) Lowering the cell weight – solid‐based cells do not need heavy steel casing.

7 (7) Safety.

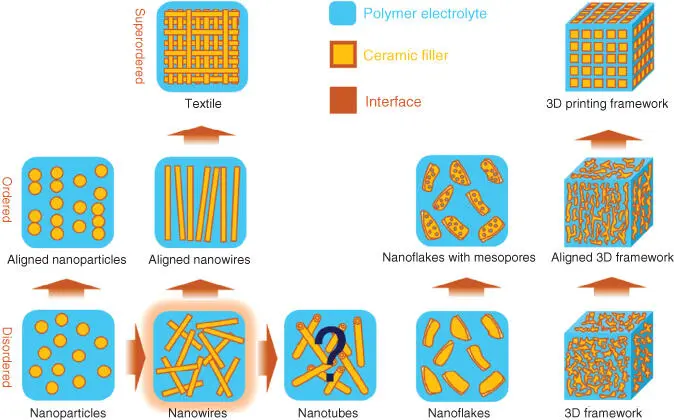

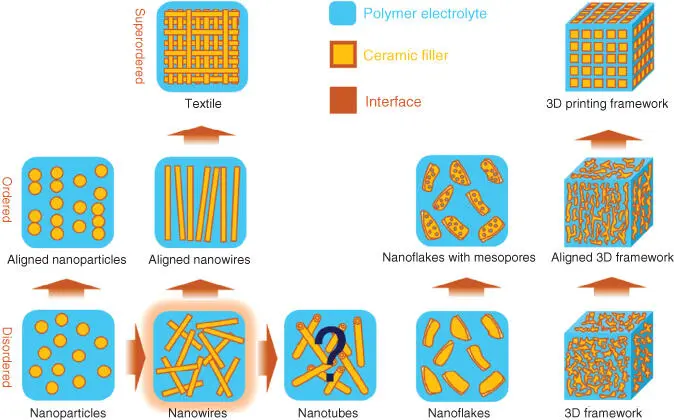

Many studies have been addressed to incorporate inert oxide ceramics particles into PE, in order to improve the mechanical properties, reduce polymer crystallinity, and thus solve the problem of low ionic conductivity of solid polymeric electrolyte (SPE). For example, various composites had been mixed into polymers (see in Figure 2.9) [94], including inert ceramic fillers [95, 96], fast ion‐conductive ceramics [97, 98], lithium salts [99], IL [100], etc.

Figure 2.9 The evolutions of morphology of ceramic filler in SCEs.

Source: Li et al. [94].

By combining the advantages of these two materials, i.e. ceramic filler and polymer material, new hybrid composite materials with high dielectric constants can be fabricated. Different types of inert ceramics had been incorporated into the polymer by blending the polymers with fillers, such as SiO 2[101], Al 2O 3[102], TiO 2[103], zeolite, etc. In 1982, Weston and Steele firstly prepared a composite by mixing PEO with Al 2O 3[104], proving that PEO after addition of fillers exhibited an improvement of mechanical properties and ionic conductivity even in a temperature exceeding 100 °C. The idea of adding ceramic fillers into polymer complex is to provide a stable solid matrix [104]. Composite polymeric materials containing fine ceramic particles are considered as heterogeneously disordered systems [105]. Later, Capuano et al. (1991) [106] studied the effects of the doping amount and particle size of LiAlO 2powder on the conductivity of solid electrolyte. The conductivity achieved the highest after the doping amount of LiAlO 2was around 10 wt.%. In other words, particle size of the inert ceramic material influenced to the conductivity of the SPE and which increased as the size is <10 μm [107]. As was reported, Al 2O 3can also effectively decrease the crystallinity and glass transition temperature of PEO, proving that the decrease of polymer crystallinity promotes the improvement of ionic conductivity [102]. Liang et al. [108] reported that PEO‐PMMA‐based composite electrolyte exhibited an improvement of the ionic conductivity from 6.71 × 10 −7to 9.39 × 10 −7S/cm, in which PEO‐PMMA and nano Al 2O 3were used as a host matrix and filler, respectively [108]. Moreover, SiO 2is also a common inert ceramic filler material used in synthesizing SPE. A composite of a PEO matrix and SiO 2fillers was reported and reached an ionic conductivity of 2 × 10 −4S/cm at ambient temperature, [109] with 2.5 wt.% filler loadings. In addition, SiO 2can be designed as a three‐dimensional skeleton doped into polymers. In recent years, PEO‐Silica aerogel was reported to achieve high ionic conductivity of 6 × 10 −4S/cm and high modulus of 0.43 GPa [110]. The mechanical properties and ionic conductivity has been enhanced by controlling powder dispersion. In addition, some studies have integrated a variety of inorganic ceramics into the polymer, and the ionic conductivity has also been improved.

Читать дальше