A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

www.wiley.com/go/wessells/urologic A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

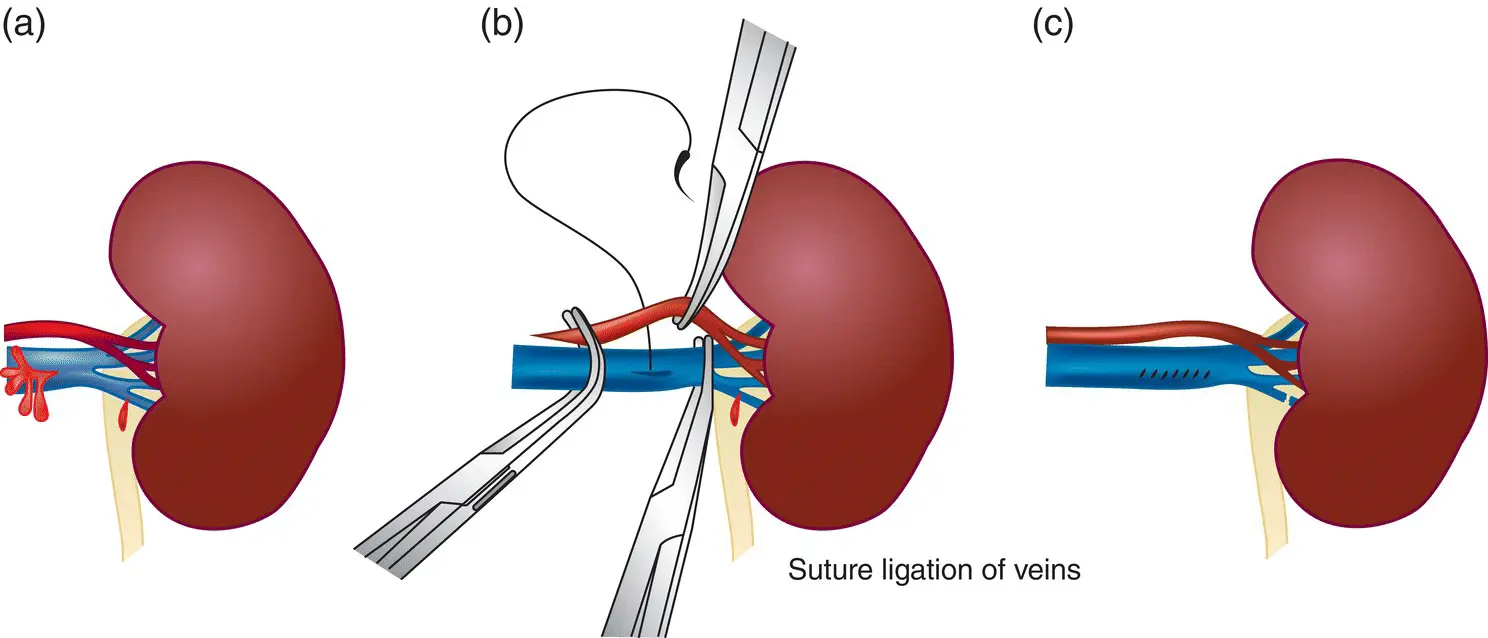

In terms of renovascular injuries, segmental arterial and venous injuries can be managed with suture ligation, realizing that ligation of segmental arteries will result in ischemia to the corresponding renal parenchyma. Repair of the main renal artery and vein should be attempted when safe with 4‐0 or 5‐0 prolene suture; however, many injuries of the main hilar vessels will result in nephrectomy ( Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5 Surgical management of vascular injuries. (a) Schematic showing injury to different portions of the renal vein. Injuries are repaired (b) or divided (c), depending on location and size.

Source: from Campbell‐Walsh, 10th Edition, with permission [39].

Issues in Operative Technique for Blunt Trauma

Renal trauma may be incompletely staged and this can be an important determinant for renal exploration. If exploration occurs before complete staging has been accomplished, a one‐shot IVP or retrograde pyelograms can be performed in the operating room (see above), or the kidney and/or ureters can be directly inspected during an abdominal exploration [79].

In cases of renal trauma, it is important to have familiarity with damage control maneuvers. It is particularly important in patients who do not have life‐threatening renal injury. In cases of uncontrolled bleeding, vascular control is paramount. Renal pedicle access by blunt dissection over psoas fascia allows for application of a large vascular clamp. Once this is done, then the kidney can be evaluated and nephron sparing techniques can be applied. Another consideration is in cases where the patient is unstable for kidney exploration and repair in the setting of active bleeding. In this case, packing the renal fossa with delated intervention is an alternative to nephrectomy. This would allow for appropriate staging in patients who were initially unstable for imaging. This staging may allow for the patient to have non‐operative management and/or angioembolization.

Complications and Follow‐Up

Complications after renal trauma are reported to be rare, occurring in about 5% of cases in modern series, although true rates of long‐term complications are difficult to define given the lack of long‐term follow‐up in the trauma population [25]. One retrospective series of grade IV and V blunt renal trauma evaluated the incidence of complications among patients who underwent immediate intervention versus those who were conservatively managed, subdividing the conservatively managed patients into successes and failures of conservative management [62]. Most were successfully managed conservatively. Of those who underwent successful conservative management (n = 142), 10.6% developed urinoma (n = 15) and 16.9% had hematuria (n = 24). Of those who failed conservative management (n = 12), 8.3% developed urinoma (n = 1) and 8.3% had persistent hematuria (n = 1).

Table 1.3 Long‐term follow‐up recommendations.

| AUA [34] | EAU [81, 82] | SIU/WHO [30] |

|---|---|---|

| Periodic monitoring of blood pressure up to a year after injury. Do not recommend routine DMSA (dimercaptosuccinic acid) or other functional nuclear scans. | Physical exam, urinalysis, “individualized radiological investigation,” serial blood pressure monitoring, and determination of renal function. Follow‐up should continue until healing is complete and lab findings have stabilized. Monitoring may need to be continued for years to evaluate for latent renovascular hypertension. | No specific recommendations, but consensus statement does cite a study that recommends that all grade IV/V injuries follow‐up with documentation of renal function by quantitative assessment |

Short‐term monitoring and follow‐up of trauma patients as previously specified is intended to detect complications and offer appropriate additional interventions. In terms of long‐term follow‐up, there is no consensus and most trauma series do not have the luxury of long‐term follow‐up, given the difficulty in following up the acutely injured population [80]. Follow‐up recommendations are outlined in Table 1.3.

Secondary Hemorrhage

Delayed hemorrhage can be a life‐threatening complication of renal trauma that can arise as a result of the parenchymal injury itself, segmental arterial bleeding, or ruptured arteriovenous fistulas (AVFs) or pseudoaneurysm. One series of grade III–IV blunt injuries managed conservatively showed a 13–25% rate of delayed bleeds, with the caveats that this number varies significantly by series and the majority of the literature on delayed bleeds is derived from cases of penetrating trauma [83‐85]. Delayed bleeds occur most commonly in the first 2–3 weeks after trauma, although case reports have described trauma‐associated bleeds occurring as late as 15 or 20 years after the initial insult [83-84]. Renal trauma from stab wounds demonstrate the onset of secondary hemorrhage in the 2–36 day time‐frame [30, 85].

Most often, delayed hemorrhage is caused by AVF or pseudo‐aneurysm [30]. The occurrence of pseudoaneurysm after blunt renal trauma has been described in several case reports but is a rare event [83,86–88]. Pseudoaneurysms are believed to form within the surrounding tissue after an arterial injury, likely due to shear stress in blunt renal trauma, where the space around the vascular injury is temporarily tamponaded by coagulation. Eventually, the intravascular and extravascular space may recannulate after degradation of the clot and necrosis of the surrounding tissue, leading to the formation of a pseudoaneurysm which can then grow and rupture [88, 89].

AVF after blunt trauma is also a rare event and has been reported in several case reports [89–92]. The fistula is thought to form as a result of injury to an arterial and venous vessel in close proximity to one another, usually within the renal parenchyma. Initially the bleeding may be tamponaded by a clot; as the hematoma resorbs the arterial bleeding can resume, draining into the nearby lacerated vein [30].

New‐onset or worsening hematuria, flank pain or mass, a hematocrit drop, or even new‐onset hypertension, should raise suspicion of a delayed bleed. CT angiogram or conventional angiography is the preferred imaging modality, although diagnosis can be made with ultrasound in some cases. Depending on the etiology, either surgical management or super‐selective embolization is employed, with the goal of controlling the bleeding while preserving as much renal function as possible [93, 94]. Complications of embolization can include abscess, infarction, renal insufficiency, and pulmonary embolization of coils [25, 84, 94, 95].

Urinary Extravasation and Perinephric Abscess

AUA guidelines recommend that clinicians perform urinary drainage in the presence of complications such as enlarging urinoma, fever, increasing pain, ileus, fistula, or infection [34].

Renal injuries with urinary extravasation at initial presentation can for the most part be managed conservatively given the high rates (90%) of spontaneous resolution, although repeat imaging is intended to evaluate for persistent leaks, urinomas, or perinephric abscesses that require additional intervention such as stenting or percutaneous drainage [3046–48, 98]. Patients with devitalized renal parenchyma in conjunction with urinary extravasation tend to have increased morbidity and may require more aggressive management [80,96–98]. Furthermore, patients with concomitant injuries, such as pancreatic or colonic injuries, may also have a higher likelihood of developing complications [25,99–101].

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.