A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

www.wiley.com/go/wessells/urologic A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Source: from Campbell‐Walsh, 10th Edition with permission [39].

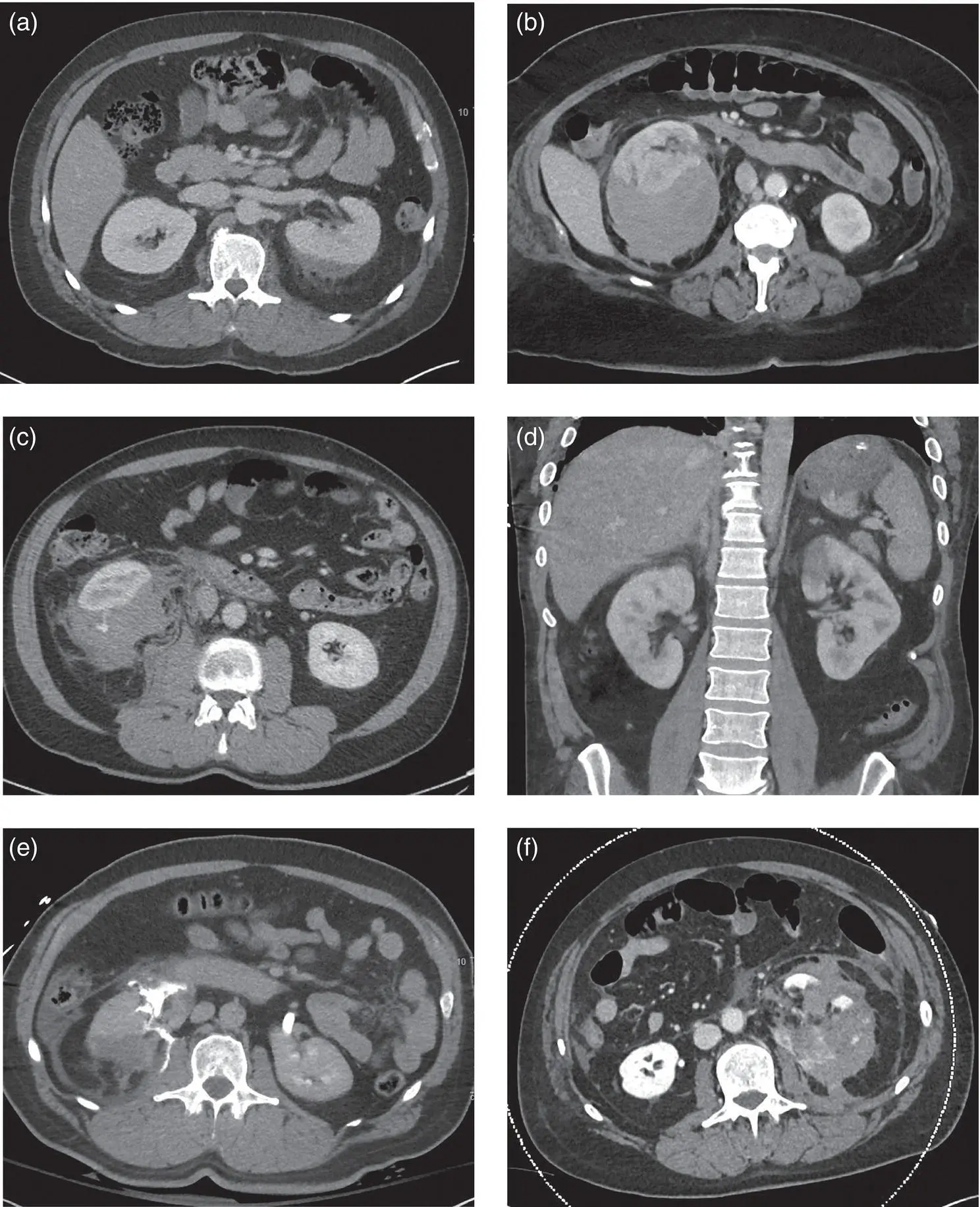

Figure 1.2 CT images of renal injuries including: (a) axial view of a left subcapsular hematoma (AAST Grade I); (b) a large right perinephric hematoma and a 2‐cm parenchymal laceration (Grade III); (c) intravascular contrast extravasation into a right perinephric hematoma (Grade III); (d) coronal view of a left upper pole perfusion defect consistent with a segmental vascular injury (Grade IV); (e) a right medial parenchymal laceration with urinary contrast extravasation (Grade IV); and (f) a shattered left kidney with hematoma, contrast extravasation and multiple parenchymal fragments (Grade V).

Source: courtesy of Alex Skokan, MD.

If CT is not available, or if the patient is brought directly to the operating room for exploration without first obtaining imaging, and renal injury is suspected due to hematuria or a perinephric hematoma, a one‐shot intravenous pyelogram (IVP) can be useful, primarily to confirm the presence of a contralateral kidney, and secondarily to identify injury of the kidney of interest, although it is much less sensitive to detect injuries than CT (see image) [44]. A one‐shot IVP is obtained by administering 2 ml/kg IV bolus of contrast with a single x‐ray of the abdomen obtained 10–15 minutes later. The radiographic image quality can be limited by under‐resuscitation, hypotension, significant edema, or renal dysfunction. One study evaluated the quality and usefulness of one‐shot IVP in the operative setting, finding that the average quality score was 3.84/5 with only 1/50 studies found to be unintelligible, and the majority (66%) were good or of excellent quality. The average usefulness score was 3.96/5, with only 1 imaging study considered worthless and the majority (72%) considered important or critical for determining urological management.

Other imaging modalities such as ultrasound, radionucleotide scintigraphy, and angiography are not recommended for initial evaluation of renal injuries but may be useful during subsequent management.

Management

Non‐operative Management

Patients with high‐grade renal injuries who are hemodynamically stable can be managed non‐operatively, involving hospital admission, intensive care monitoring, bed‐rest, hydration, and serial hematocrit checks [34]. Over time, data have shown that the majority of renal injuries can be safely managed in a non‐operative manner, with the potential benefits of preserving renal function and limiting morbidity [45].

Most stable patients with urinary extravasation can be managed non‐operatively initially, as long as they do not have concern for a renal pelvis or ureteropelvic junction injury. Management may involve bladder drainage in order to facilitate collecting system drainage and/or antibiotics, although evidence is lacking to support these. Urinary extravasation can resolve spontaneously without intervention, with rates of spontaneous resolution near to 90% [46–48]. Guidelines support initial non‐operative management of patients with urinary extravasation, given the possibility of spontaneous resolution and avoiding risks of injury during stent placement, risks of anesthesia, and the possibility of retained stents due to patients being lost to follow‐up [34]. If there is any concern for complications with non‐operative management (such as fever, enlarging urinoma, ileus, infection) or the urinary extravasation is found to be persistent on repeat imaging, ureteral stent placement is indicated. Some of these patients will require additional drainage with a nephrostomy tube and/or perinephric drain [47-48].

The AUA Urotrauma Guidelines suggest that patients who sustain high‐grade injury (AAST IV‐V) that are managed non‐operatively should undergo repeat imaging after 48 hours or earlier, if needed, given the higher risk of complications and possibility of requiring future intervention [34]. In addition, conservatively managed patients who have clinical signs of complications – such as fevers, persistent severe pain, dropping hematocrit, hemodynamic instability, worsening flank or abdominal pain – should also undergo repeat imaging [34].

Repeat imaging may be tailored, based on an individuals' specific injury [49]. A recent analysis of repeat imaging in patients with grade IV and V renal trauma at three Level 1 trauma centers over 19 years (1999–2017) demonstrated that in asymptomatic patients, one in eight patients would need to undergo repeat imaging to identify a patient who needs surgical intervention. The primary goal of repeat imaging is to evaluate for complications and to evaluate clinical deterioration. Hence, it may be more worthwhile to obtain repeat imaging in patients who have signs of bleeding or history of collecting system injury as in this study. Stable patients with grade I–III injuries generally do not require repeat imaging. Repeat imaging with ultrasound instead of CT has also been advocated, based on studies showing that imaging of asymptomatic patients would not have altered clinical decision‐making and concerns that standardized repeat imaging with CT exposes patients to unnecessary radiation exposure, and drives up healthcare costs, and ultrasound has been shown to be an effective alternative for detecting clinically relevant complications [20, 50, 51].

Indications for Intervention

As per AUA guidelines, “the surgical team must perform immediate intervention (surgery or angioembolization in selected situations) in hemodynamically unstable patients with no or transient response to resuscitation” [34]. Intervention is also required in the face of an enlarging or pulsatile perinephric hematoma seen on exploratory laparotomy, suspected renal pedicle avulsion, or a ureteropelvic junction disruption [52]. Depending on the clinical circumstances, these patients may require surgery or angioembolization. Several studies have evaluated high‐risk criteria for bleeding associated with renal trauma, finding that intravascular contrast extravasation, perinephric hematoma of more than 3.5 cm in distance from the parenchymal edge to the hematoma edge, and medial renal laceration are risk factors associated with surgery for hemodynamic instability and the presence of two or more of these risk factors predicts the need for intervention [41–43, 53]. Studies have also evaluated these predictors for angiographic embolization, finding that perirenal hematoma size and intravascular contrast extravasation are indicators for embolization [54]. One study showed that patients without intravascular contrast extravasation and who have a perirenal hematoma rim distance of less than 25 mm are unlikely to benefit from angioembolization, and that combining CT scan‐specific criteria such as intravascular contrast extravasation, perirenal hematoma size, and discontinuity of Gerota's fascia, can be predictive of the need for renal embolization [55]. Intravascular contrast extravasation alone is not an indication for angioembolization or other interventions. It is important to consider the hemodynamic status of the patient and blood transfusion requirements.

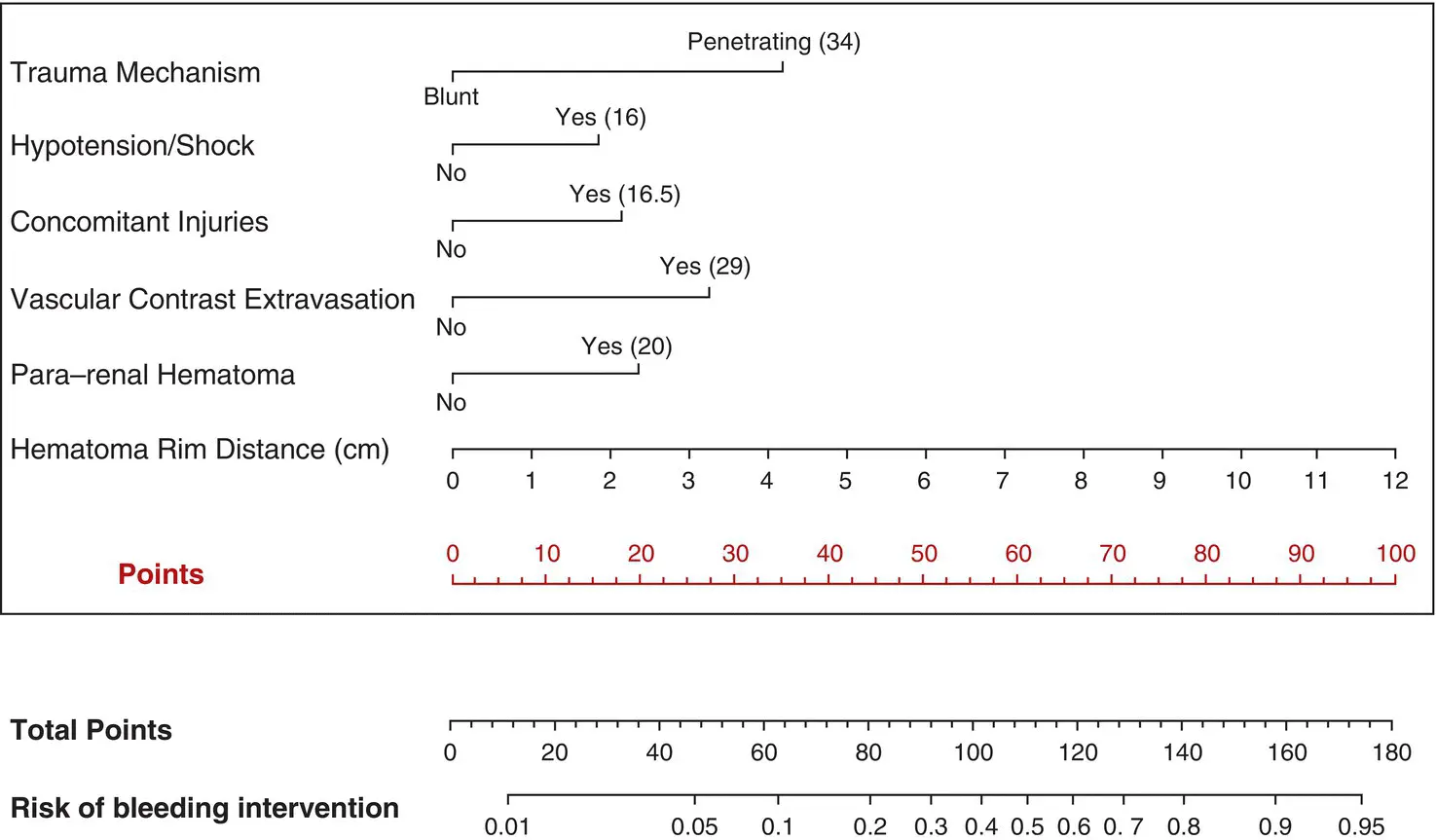

Building on these single institution series, the Multi‐institutional Genito‐Urinary Trauma Study Group created a nomogram to predict bleeding interventions after high‐grade renal injury [56]. The variables in the nomogram ( Figure 1.3) include mechanism of injury, hemodynamic status, associated injuries, and the following radiographic features: intravascular contrast extravasation; para‐renal hematoma; and hematoma size.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.