A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

www.wiley.com/go/wessells/urologic A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Figure 1.3 Nomogram predicting bleeding interventions after high‐grade renal injury. Points are awarded for “Yes” responses for the first 5 parameters; the Hematoma Rim Distance is scored by tracing a line down to the Points scale in red. Total Points is based on the sum of the first 5 scores and the points from the scale in red. Source: from the MiGUTS Study, with permission [56].

With an area under the ROC (receiver operator characteristic) curve of 0.83, the nomogram performed better than AAST grade alone (which was not included in the nomogram). The nomogram, once externally validated, could provide a means to incorporate imaging data into decision‐making on renal trauma management. Future work will be necessary to determine how to apply the nomogram in clinical care settings. Potential applications include its use to triage patients to ICU (intensive care unit) versus floor care for isolated grade III and IV injuries; ensure appropriateness of transfer from a lower to higher trauma designation hospital; to select treatment of bleeding with embolization versus transfusion alone; and support decisions for operative management [57].

Non‐operative Versus Operative Management

Published series of blunt trauma patients suggest that when patients are matched by grade and mechanism injury in an operative cohort compared to a more conservatively managed cohort, the rate of nephrectomy is lower, complication rates are similar, and length of hospital stay is shorter with non‐operative management [45–47]. Further supporting these data, hospitals that have changed their policy toward renal trauma management to adopt a non‐operative approach have shown significant (two‐ to six‐fold) decreases in renal exploration and nephrectomy without seeing an increase in complications [46, 58, 59].

In comparing series of grade IV blunt injuries that were managed non‐operatively versus those who underwent exploration, higher rates of exploration are associated with higher rates of nephrectomy [45]. Finally, there are published series of patients who have sustained blunt grade V injuries, usually complex parenchymal lacerations (e.g. shattered kidney), who have been managed non‐operatively. One such series showed a decreased rate of transfusions, shorter ICU length of stay, and fewer complications for the conservatively managed patients [60]. A recent series showed that just over 50% of grade V injuries were able to be managed non‐operatively [61].

Predictors of Failure of Non‐Operative Management in Blunt Renal Trauma

Of patients with blunt trauma that are managed non‐operatively, some will ultimately require intervention. One series evaluated 154 patients (74.8%) with grade IV and V blunt renal trauma, who were initially managed non‐operatively, with a non‐operative management failure rate of 7.8% [62]. The vast majority of the patients who failed non‐operative management did so because of their kidney injury and none of these patients had complications as a result of delayed operative management. The mean time to failure was just over 24 hours and the majority (83.3%) failed due to hemodynamic instability. Independent predictors based on multivariate analysis found that those who were older than 55 years of age or who were injured as a result of a motor vehicle collision were more likely to fail non‐operative management.

Patients with a devitalized parenchymal segment were more likely to require delayed surgical intervention in a series of grade IV and V blunt renal injuries [46]. Of 40 patients with grade III–V blunt renal injury initially managed non‐operatively, the risk of delayed nephrectomy in three was associated with grade IV injuries and secondary hemorrhage which necessitated intervention [8].

Management of Renal Trauma in Children

Many studies have evaluated management of renal trauma in children, with the consensus being that most cases of pediatric renal trauma can be safely managed non‐operatively [63–67]. Rates of delayed intervention vary from very low to as high as 30–40% [64,68–70]. In one series of 16 patients managed non‐operatively, 44% required intervention with a mean time to intervention of 11 days; collecting system clot and larger urinoma were significant predictors of failure of non‐operative management [70]. Consistent with findings in adults, another group found that medial contrast extravasation among grade IV renal injuries was a significant predictor of failure of non‐operative management [71].

Given the lack of age specific guidelines, pediatric blunt renal trauma guidelines were established recently by the Eastern Association for Surgery of Trauma and Pediatric Trauma society [72]. These guidelines advocate for nonoperative management in high‐grade trauma sustained by hemodynamically stable patients based on synthesis of evidence. For those undergoing intervention, angioembolization is highly recommended. Finally, routine blood pressure monitoring is recommended after injury.

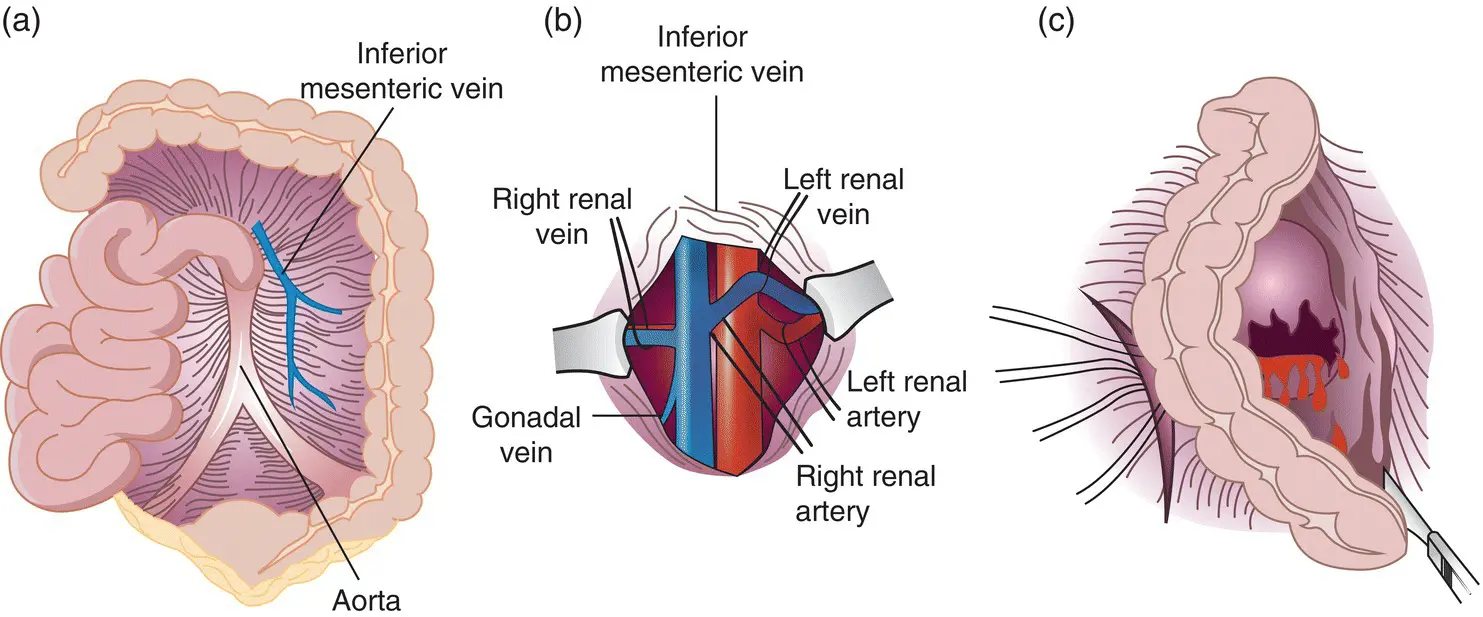

Operative Technique

Absolute criteria for renal exploration include life‐threatening hemorrhage with hemodynamic instability, renal pedicle avulsion, and expanding, pulsatile, or uncontained retroperitoneal hematoma [25]. Renal exploration and repair in the acute injury setting is accomplished through a midline abdominal incision. While prior literature supported early vascular control, more recent literature is inconclusive on this approach [73-77]. Surgical exploration often results in nephrectomy [4]. The renal vessels can be isolated before Gerota's fascia is opened in order be able to rapidly occlude hilar vessels if significant bleeding is encountered; some advocate that this technique may lead to a lower rate of nephrectomy, whereas other data have shown no difference in nephrectomy rate, transfusion requirements, or blood loss with potential for increased operative time [76, 77]. If early vascular control is desired, an incision can be made in the mesentery medial to the inferior mesenteric vein and extended to the ligament of Treitz in order to expose the aorta [78] ( Figure 1.4). The left renal vein will be visualized first as it passes anterior to the aorta and the renal arteries can then be identified posterior to the left renal vein, and the right renal vein will be identified anterior to the right renal artery. Once the hilar vessels have been isolated, the colon can then be reflected medially by incising the peritoneum lateral to the colon and exposing Gerota's fascia. The kidney can then be fully exposed in order to identify any injuries. The other approach to the renal hilum involves initial reflection of the colon and its mesentery, keeping out of Gerota's fascia, followed by isolation of the renal hilum for early vascular control, and renorrhaphy, partial nephrectomy, or nephrectomy.

Figure 1.4 Surgical approach to renal vessels and hilum. (a) Relationship between the aorta, posterior peritoneum, and inferior mesenteric vein. (b) Window in posterior peritoneum made between aorta and inferior mesenteric vein demonstrating each renal artery and vein. (c) After vascular exposure and isolation, exploration of Gerota fascia obtained by incising the peritoneum lateral to the descending colon (for a left‐sided injury).

Source: from Campbell‐Walsh, 10th Edition, with permission [39].

Repair of the kidney depends on the injuries present, and should involve debridement of nonviable tissue, suture ligation of individual bleeding vessels to obtain hemostasis, watertight closure of any collecting system defects, and closure or re‐approximation of the parenchymal defect when possible. If parenchymal closure is difficult, techniques such as thrombin‐soaked Gelfoam bolsters or omental interposition or pedicle flap may be helpful.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.