A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

www.wiley.com/go/wessells/urologic A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies

A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Children may have a higher risk of significant renal injury from blunt trauma and this is thought to be related to the proportionately larger kidney for their body size as compared to that of adults, the possibility of children retaining fetal lobulations that may predispose to parenchymal disruption, and the pediatric kidney having less protection due to lower perirenal fat content, weaker abdominal muscles, and less ossification of the rib cage [23, 24].

The proportion of patients with renal trauma found to have congenital anomalies varies, depending on different series, ranging from 1 to 23% [23]. One series that reviewed 193 pediatric renal trauma patients found that just over 8% of patients had a congenital anomaly [25]. Data regarding renal trauma and congenital anomalies is somewhat mixed, with most studies suggesting that congenital anomalies increase the risk of significant renal injury and decrease the possibility of renal salvage, while other series suggest that there is no effect on morbidity or mortality [25-30]. Overall consensus is that pre‐existing renal anomalies likely increase the vulnerability of kidneys in blunt renal trauma [4, 30]. They may also complicate the management of a renal laceration involving the collecting system or parenchyma (e.g. horseshoe kidney with complex arterial vasculature, UPJ (ureteropelvic junction) obstruction, etc.).

Diagnosis

Workup

A complete history, including the crash mechanics and velocity of impact as well as known pre‐existing renal disease or abnormality, should be obtained if possible. For example, renal injury frontal and side impact collisions may be impacted by direct contact from seatbelt and steering column [31]. Seatbelt use and airbag deployment are also important characteristics to note; absence of a seatbelt is associated with higher probability of thoracoabdominal injury [32]. Compared to individuals who did not have airbag deployment with vehicle collision, those with frontal and side airbags have a 46 and 53% decrease in renal injury, respectively [33]. Vehicle characteristics are important given the association of increased crash test rating (i.e. safer car) with lower likelihood of thoracoabdominal injury [32].

Blunt trauma caused by a blow to the flank, rib fracture, or rapid deceleration injury should make clinicians suspicious for possible renal injury. Such mechanisms include injuries related to sports (in particular ice hockey, soccer, and football), ski and snowboarding, and motor vehicle versus pedestrian. Signs of renal injury from blunt trauma that may be noted on physical examination include gross hematuria, flank hematoma, and abdominal or flank tenderness. Vital signs are important to obtain and monitor both in the field and upon arrival at the hospital, as hemodynamic stability drives evaluation and management of renal trauma. Laboratory examinations, including a creatinine, hematocrit, and urinalysis with microscopic analysis to evaluate for hematuria, should be obtained.

Radiographic Evaluation

The American Urological Association (AUA) has released guidelines to provide indications for imaging of suspected renal trauma [34]. Patients sustaining blunt injury that require diagnostic imaging are those who have gross hematuria, or those who have a systolic blood pressure of less than 90 mmHg with microscopic hematuria. Additionally, any patients who are stable but have a mechanism of injury (e.g. fall from a great height) or physical examination (see above) findings concerning renal injury should also be imaged, as trauma patients may have renal injury, even in the absence of hematuria or shock [14, 35]. Based on the AUA Urotrauma Guidelines, children should be imaged with the same modality and criteria as adults.

If imaging is obtained, a contrast enhanced CT (computed tomography) abdomen pelvis with immediate and delayed images is recommended, in order to visualize the kidney parenchyma and collecting system and to look for evidence of bleeding or urinary extravasation. The immediate phase is typically an arterial or early venous phase, which highlights the renal parenchyma and can be useful for evaluating for parenchymal laceration, intravascular contrast extravasation, and hematoma. The delayed phase, typically obtained at 10–15 minutes after contrast administration, is useful to evaluate the collecting system of the kidney and the ureter. In addition, subtle findings on initial venous imaging such as perinephric stranding, hematoma, and low‐density retroperitoneal fluid may prompt imaging with delayed phase to evaluate for a ureteropelvic or ureteral injury; a large medial urinoma or contrast extravasation on delayed images without distal ureteral contrast visualized is concerning for a renal pelvis or ureteral avulsion injury [36, 37].

Evaluating the size of a perinephric hematoma, the presence of intravascular contrast extravasation, and a medial laceration on CT can be useful, as these factors can predict bleeding complications and help guide management, as discussed in the management section (below).

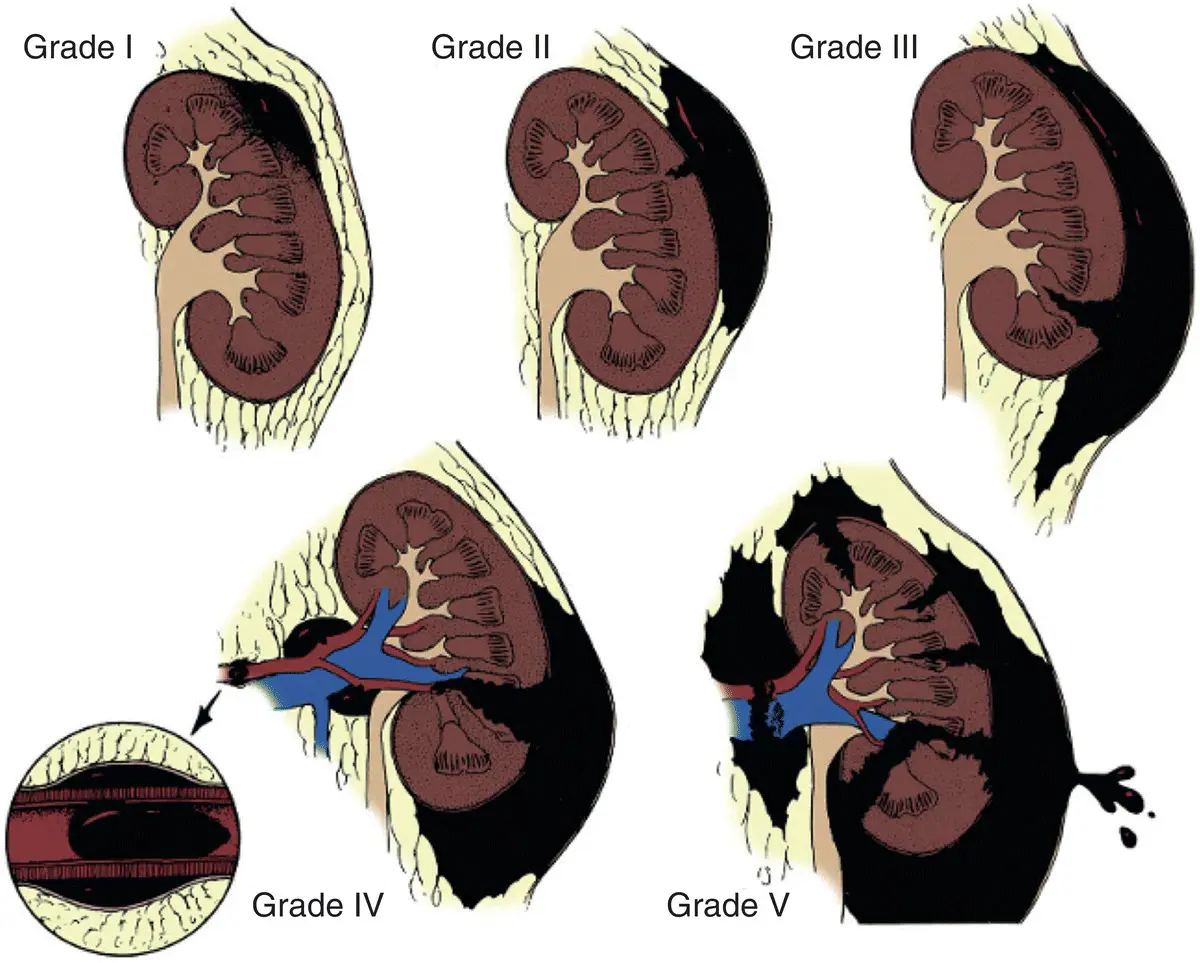

Renal injuries are classified by the Organ Injury Scaling of the American Association for Surgery of Trauma (AAST) [38] ( Table 1.2, Figures 1.1and 1.2). Grade I injuries are renal contusions or subcapsular hematomas without parenchymal laceration. Grade II injuries involve perirenal hematomas of the renal retroperitoneum or parenchymal renal lacerations that extend for less than 1 cm. Once the laceration extends for greater than 1 cm into the renal parenchyma, this becomes a grade III injury, with an elevation to grade IV if there is collecting system involvement (i.e. urinary contrast extravasation from the renal collecting system). Grade IV injuries also include contained hilar vascular injuries, such as injury to the main renal artery or vein. Grade V injuries are so‐called “shattered” kidneys and renal hilar avulsion injuries that cause devascularization of the kidney. Revisions have been proposed to this classification in order to include previously undescribed injuries and reclassify other injuries to facilitate more appropriate alignment of classification and management/outcomes, particularly in order to better classify vascular (such as segmental vessel injury) and collecting system injuries, though these revisions have not been formally accepted [40–43].

Table 1.2 2018 American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) organ injury scale [38].

| Grade | Description of Injury |

|---|---|

| I | Subcapsular hematoma and/or parenchymal contusion without laceration |

| II | Perirenal hematoma confined to Gerota fascia Renal parenchymal laceration ≤1 cm depth without urinary extravasation |

| III | Renal parenchymal laceration >1.0 cm parenchymal depth without collecting system rupture or urinary extravasation Any injury in the presence of a kidney vascular injury or active bleeding contained within Gerota fascia |

| IV | Parenchymal laceration extending into urinary/collecting system with urinary extravasation Renal pelvic laceration and/or complete ureteropelvic disruption Segmental renal vein or artery injury Active bleeding beyond Gerota fascia into retroperitoneum or peritoneum Segmental or complete kidney infarction(s) due to vessel thrombosis without active bleeding |

| V | Main renal artery or vein laceration or avulsion of hilum Devascularized kidney with active bleeding Shattered kidney with loss of identifiable parenchymal renal anatomy |

Figure 1.1 American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) Organ Injury Severity Score for the Kidney.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Clinical Guide to Urologic Emergencies» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.