Figure 3.1. A 55‐year‐old woman (a and b) with a one‐week history of pain and swelling in the left parotid gland. No pus was present at Stensen duct. The diagnosis was community acquired acute bacterial parotitis. Conservative measures were instituted including the use of oral antibiotics, warm compresses to the left face, sialogogues, and digital massage. Two weeks later, she was asymptomatic, and physical examination revealed resolution of her swelling (c and d).

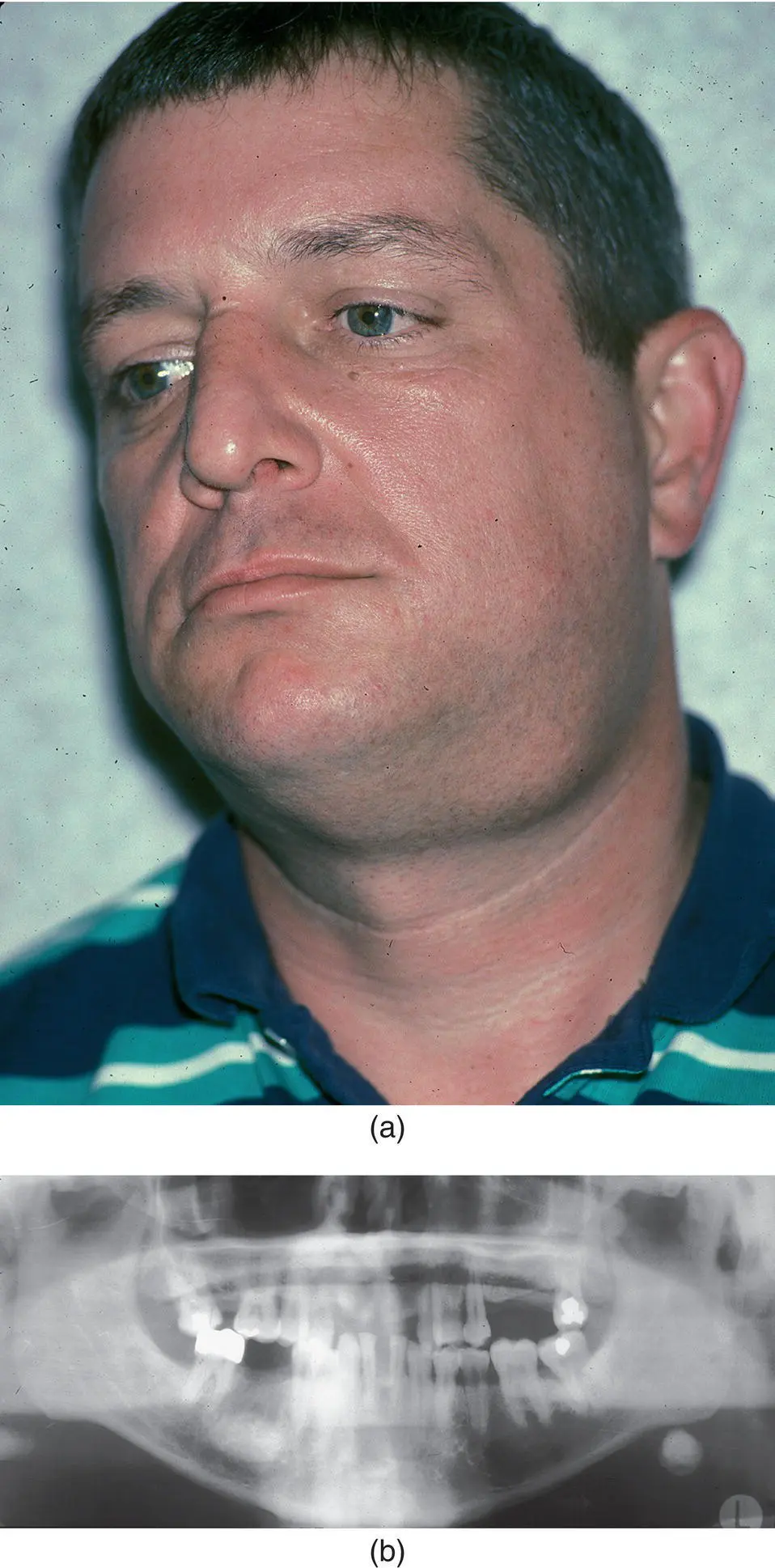

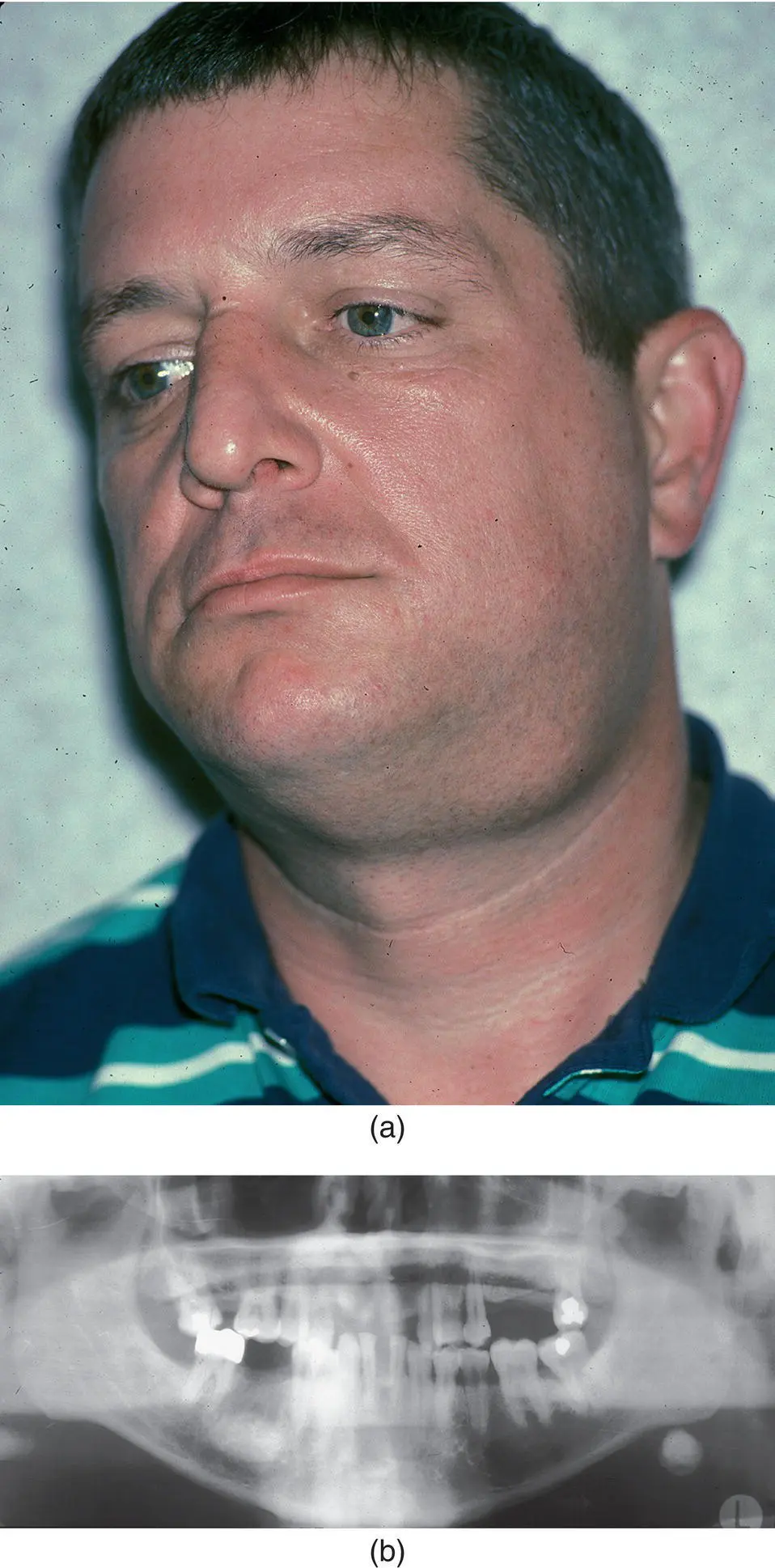

Figure 3.2. A 45‐year‐old man (a) with a six‐month history of left submandibular pain and swelling. A clinical diagnosis of chronic submandibular sialadenitis was made. A screening panoramic radiograph was obtained that revealed the presence of a large sialolith in the gland (b). As such, the obstruction of salivary outflow by the sialolith was responsible for the chronic sialadenitis. This case underscores the importance of obtaining a screening panoramic radiograph in all patients with a clinical diagnosis of sialadenitis, as it permitted expedient diagnosis of sialolithiasis in this case.

Table 3.1. Classification of salivary gland inflammation/infection.

| Bacterial infectionsAcute bacterial parotitis Chronic bacterial parotitis Chronic recurrent juvenile parotitis Acute suppurative submandibular sialadenitis Chronic recurrent submandibular sialadenitis Acute allergic sialadenitis Viral infectionsMumps HIV/AIDS Cytomegalovirus Fungal infections Mycobacterial infectionsTuberculosis Atypical mycobacteria Parasitic infections Autoimmune‐related inflammationSystemic lupus erythematosus Sarcoidosis Sjögren syndrome |

Table 3.2. Risk factors associated with salivary gland inflammation/infection.

| Modifiable risk factorsDecreased intravascular volume Decreased input (dehydration/prerenal azotemia) Increased output (chronic vomiting/diarrhea) Recent surgery and anesthesia Malnutrition Medications Antihistamines Diuretics Tricyclic antidepressants Phenothiazines Antihypertensives Barbiturates Anti‐sialogogues Anticholinergics Chemotherapeutic agents Sialolithiasis Oral infection Non‐modifiable risk factorsAdvanced age Relatively non‐modifiable risk factorsRadiation therapy where cytoprotective agents were not administered Renal failure Hepatic failure Congestive heart failure HIV/AIDS Diabetes mellitus Anorexia nervosa/bulimia Cystic fibrosis Cushing disease |

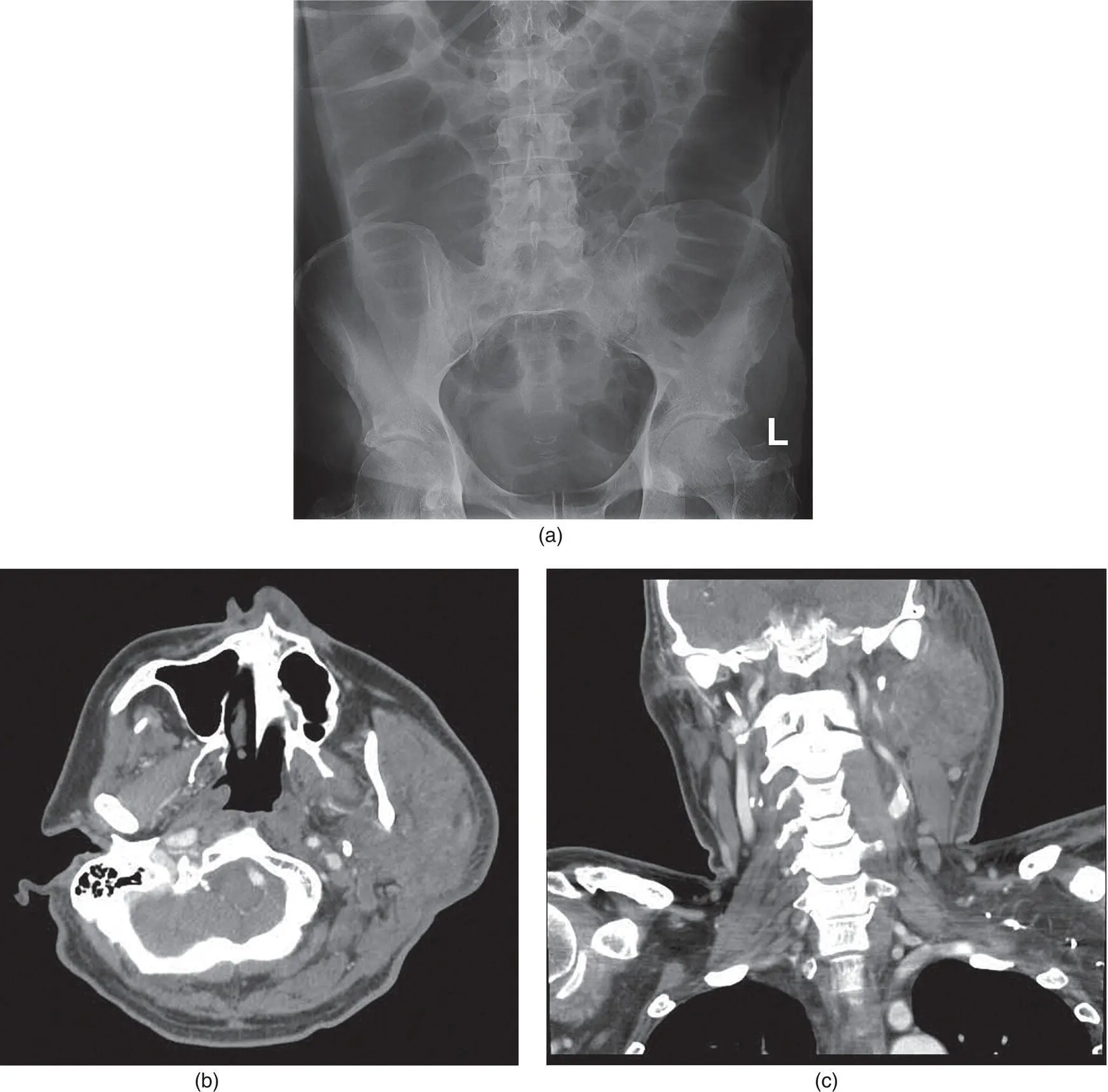

Evaluation and treatment of the patient with sialadenitis begins with a thorough history and physical examination. The setting in which the evaluation occurs, for example a hospital ward vs. an office, may provide information as to the underlying cause of the infection. Many cases of acute bacterial parotitis (ABP) occur in elderly debilitated patients, some of whom are admitted to the hospital, who demonstrate inadequate intravenous fluid resuscitation (insufficient intake) or excessive volume loss (excessive output) ( Figure 3.3) or third‐spacing of fluid resulting in hypovolemia. This notwithstanding, many cases of acute bacterial parotitis and submandibular sialadenitis are evaluated initially in an outpatient setting.

The formal history taking process begins by obtaining the patient's chief complaint. Sialadenitis commonly begins as swelling of the salivary gland with pain due to stretching of that gland's sensory innervated capsule. Patients may or may not describe the perception of pus associated with salivary secretions, and the presence or absence of pus may be confirmed on physical examination.

History taking is important to disclose the acute or chronic nature of the problem that will significantly impact on how the sialadenitis is ultimately managed. Regarding the prognosis and the anticipation for the possible need for future surgical intervention, an acute sialadenitis is somewhat arbitrarily classified as one where symptoms are less than one month in duration, while a chronic sialadenitis is defined as having been present for longer than one month. In addition, the history will permit the clinician to assess the risk factors associated with the condition. In so doing, the realization of modifiable versus relatively non‐modifiable versus non‐modifiable risk factors can be determined. For example, dehydration, recent surgery, oral infection, and some medications represent modifiable risk factors predisposing patients to sialadenitis. On the other hand, advanced age is a non‐modifiable risk factor, and chronic medical illnesses and radiation therapy constitute relatively non‐modifiable risk factors associated with these infections. The distinction between modifiable and relatively non‐modifiable risk factors is not intuitive. For example, dehydration is obviously modifiable. The sialadenitis associated with diabetes mellitus may abate clinically as evidenced by decreased swelling and pain; however, the underlying medical condition is not reversible. The same is true for HIV/AIDS. While much medical comorbidity can be controlled and palliated, these conditions often are not curable such that patients may be fraught with recurrent sialadenitis at unpredictable time frames following the initial event. As such, these and many other risk factors are considered relatively non‐modifiable.

Other features of the history, such as the presence or absence of prandial pain, may direct the physical and radiographic examinations to the existence of an obstructive phenomenon. The presence of medical conditions and the use of medications to manage these conditions are very important elements of the history taking of a patient with a chief complaint suggestive of sialadenitis. They may be determined to be of etiologic significance when the physical examination confirms the diagnosis of sialadenitis. Musicians playing wind instruments who present for evaluation of bilateral parotid swelling and pain after a concert may have acute air insufflation of the parotid glands as part of the “trumpet blower's syndrome” (Miloro and Goldberg 2002). Recent dental work, specifically the application of orthodontic brackets, may result in traumatic introduction of bacteria into the ductal system with resultant retrograde sialadenitis. Deep facial lacerations proximal to an imaginary line connecting the lateral canthus of the eye to the oral commissure, and along an imaginary line connecting the tragus to the mid‐philtrum of the lip may violate the integrity of Stensen duct. While a thorough exploration of these wounds with cannulation and repair of Stensen duct is meticulously performed, it is possible for foreign bodies to result in obstruction of salivary flow with resultant parotid swelling. Numerous autoimmune diseases with immune complex formation can also be responsible for sialadenitis, and confirmation of their diagnosis should be sought during the history and physical examination.

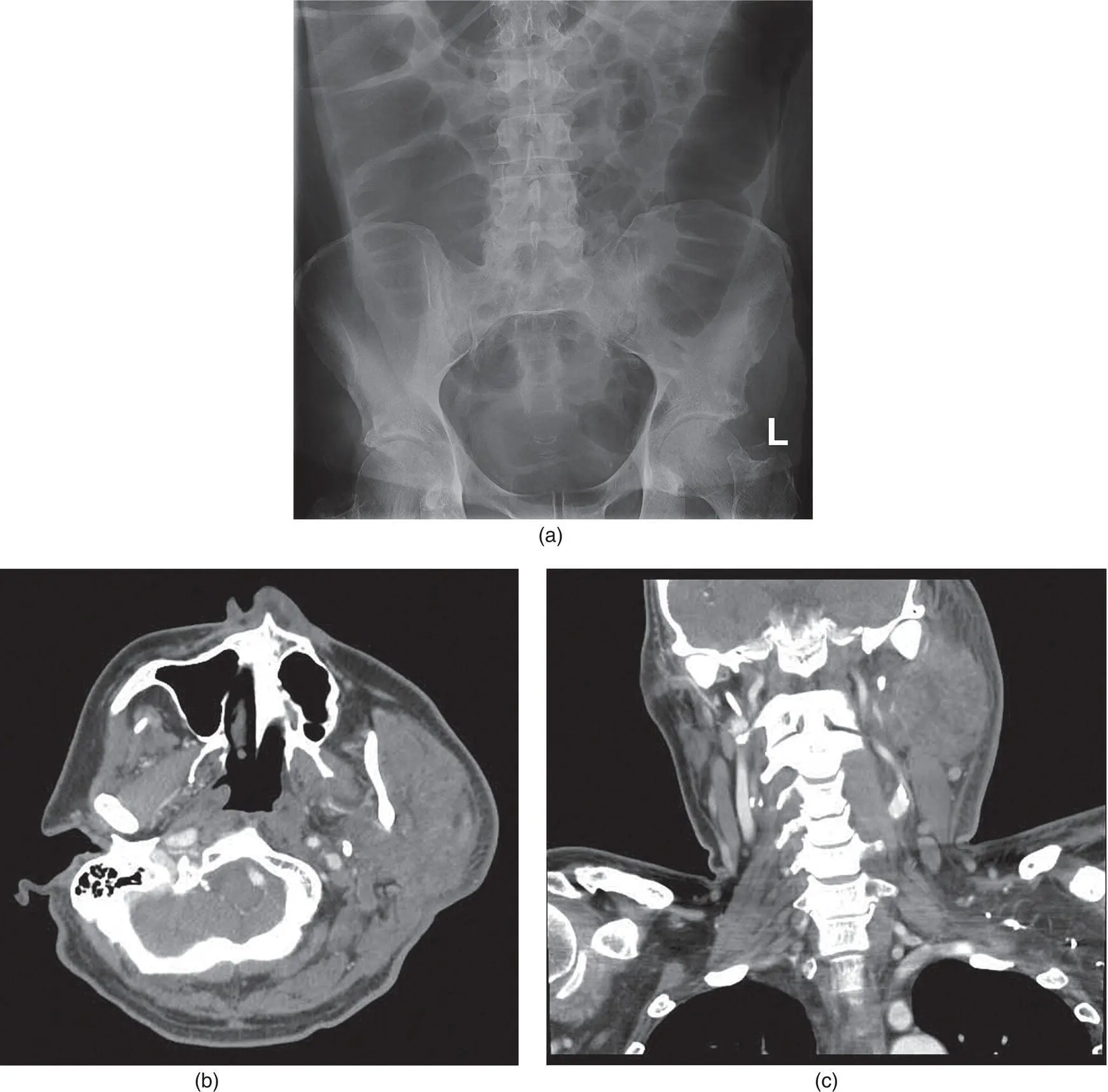

Figure 3.3. A 35‐year‐old man with a toxic megacolon (a) associated with Clostridium difficile diarrhea. He developed a left parotitis (b and c) due to a severe depletion of his intravascular volume.

Читать дальше