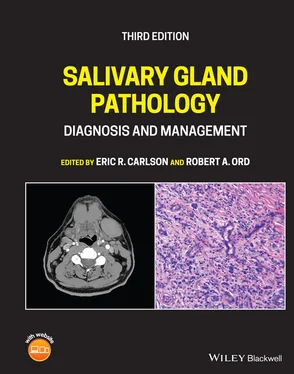

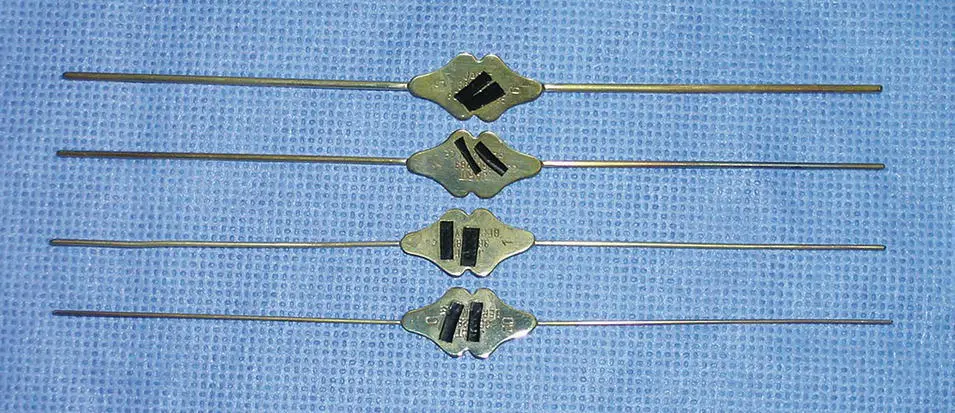

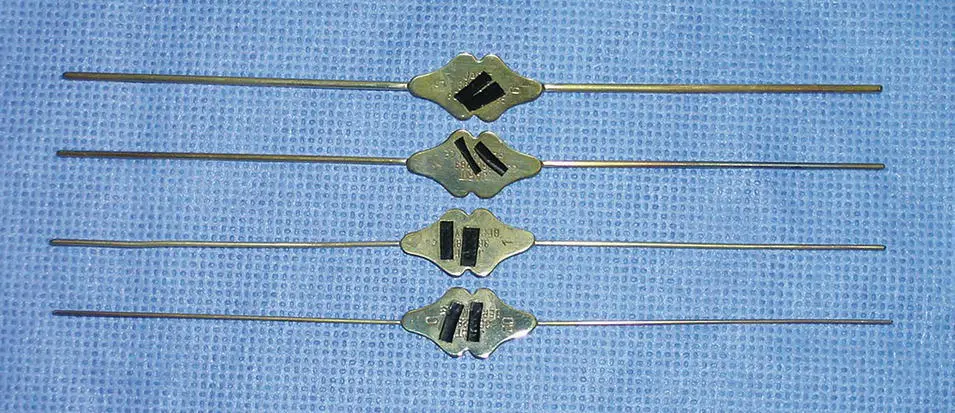

After the patient's history has been obtained, the physical examination should be performed. In the patient with suspected sialadenitis, the examination is focused on the head and neck and begins with the extraoral examination followed by the intraoral examination. Specifically, the salivary glands should be assessed in a bimanual fashion for asymmetries, erythema, tenderness to palpation, swellings, induration, and warmth. In so doing, one of the most important aspects of this examination is to rule out the presence of a tumor (Carlson 2013). A neoplastic process of the parotid gland presents as a discrete mass within the gland, with or without symptoms of pain. An infectious process presents as a diffuse enlargement of the parotid gland that is commonly symptomatic. It is possible for an indurated inflammatory lymph node within the parotid gland to simulate neoplastic disease. The distinction in the character of the parotid gland is important to not waste time treating a patient for an infectious process when they have a tumor in the parotid gland, particularly in the event of a malignancy. Evidence of facial trauma, including healing facial lacerations or ecchymoses, should be ascertained. The intraoral examination focuses on the observation of the quality and quantity of spontaneous and stimulated salivary flow. It is important to understand, however, that the anxiety and sympathomimetic response associated with the examination is likely to decrease the patient's salivary flow. Nonetheless, an advanced case of sialadenitis will often allow the clinician to appreciate the flow of pus from the salivary ducts ( Figures 3.4and 3.5). If pus is not observed, mucous plugs, small stones, or “salivary sludge” may be noted. As part of the examination, it may be appropriate to perform cannulation of the salivary duct with a series of lacrimal probes ( Figure 3.6). This maneuver may dislodge obstructive material or diagnose an obstruction. The decision to perform this instrumentation, however, must not be made indiscriminately. This procedure may introduce bacteria into the salivary duct that normally colonize around the ductal orifice, thereby permitting retrograde contamination of the gland. Prepping the Wharton duct or Stensen duct with a Betadine solution prior to lacrimal probe cannulation is therefore advised. This procedure is probably contraindicated in patients with acute bacterial parotitis and acute bacterial submandibular sialadenitis. The head and neck examination concludes by palpating the regional lymph nodes, including those in the preauricular and cervical regions.

Figure 3.4. A severe case of hospital acquired parotitis related to insufficient rehydration of this patient.

Figure 3.5. A mild case of community acquired parotitis is noted by the expression of pus at the left Stensen duct.

Figure 3.6. Lacrimal probes are utilized to probe the salivary ducts. The four shown in this figure incrementally increase in size. Cannulation of salivary ducts begins with the smallest probe and proceeds sequentially to the largest to properly dilate the duct. It is recommended that patients initiate a course of antibiotics prior to probing salivary ducts to not exacerbate the sialadenitis by introducing oral bacteria proximally into the gland.

Radiographs of the salivary glands may be obtained after performing the history and physical examination. Since radiographic analysis of the salivary glands is the subject of Chapter 2, this discipline will not be discussed in detail in this chapter. Nonetheless, plain films and specialized imaging studies may be of value in evaluating patients with a clinical diagnosis of sialadenitis. Obtaining screening plain radiographs such as a panoramic radiograph and/or an occlusal radiograph is important data to obtain when a history exists that suggests an obstructive phenomenon. The presence of a sialolith on plain films, for example, represents very important diagnostic information to direct therapy. It permits the clinician to identify the etiology of the sialadenitis and to remove the stone at an expedient time frame. Such expedience may permit the avoidance of chronicity such that gland function can be maintained.

Bacterial Salivary Gland Infections

ACUTE BACTERIAL PAROTITIS

World history indicates that acute bacterial parotitis (ABP) played a significant role in its chronicles, particularly in the United States. We are told that the first case of acute bacterial parotitis occurred in Paris in 1829 in a 71‐year‐old man where the parotitis progressed to gangrene (McQuone 1999; Miloro and Goldberg 2002). As mumps plays a role in the differential diagnosis of infectious parotitis, Brodie's distinction between acute bacterial parotitis and viral mumps in 1834 represents a major inroad into the understanding of this pathologic process (Brodie 1834; Goldberg and Bevilacqua 1995). Prior to the modern surgical era, ABP was not uncommonly observed, and indeed represented a dreaded complication of major surgery, with a mortality rate as high as 50% (Goldberg and Bevilacqua 1995). Ineffective postoperative intravascular volume repletion with resultant diminished salivary flow and dry mouth were the norm rather than the exception. President Garfield sustained a gunshot wound to the abdomen in July 1881 and developed chronic peritonitis and ultimately died several weeks later. The terminal event was described as suppurative parotitis that led to sepsis (Goldberg and Bevilacqua 1995; Carlson 2009).

It has been pointed out that upper and lower aerodigestive tract surgeries require patients to be without oral nutritional intake or with limited oral intake postoperatively (McQuone 1999). The reduction of salivary stimulation predisposes these patients to acute bacterial parotitis, with an estimated incidence of 1 in 1000 postoperative patients (Andrews et al. 1989). Other statistics showed 3.68 cases per 10,000 operations in the preantibiotic era compared with 0.173 in 10,000 operations in the antibiotic era (Robinson 1955). The prophylactic use of antibiotics has probably contributed to the reduction of cases of acute bacterial parotitis. In addition, intraoperative and postoperative intravenous hydration became well accepted in the 1930s, particularly during World War II, therefore also contributing to the reduction in the incidence of ABP. In 1958, Petersdorf reported seven cases of staphylococcal parotitis and the 1960s ushered in several reports of ABP as a disease making a comeback (Petersdorf et al. 1958; Goldberg and Bevilacqua 1995). Of Petersdorf's seven cases, five of the patients had undergone surgery, and two of the patients died in the hospital. Oral and maxillofacial surgeons began to report cases of ABP in the literature in the 1960s (Goldberg and Harrigan 1965; Guralnick et al. 1968). These cases were most likely due to the emergence of penicillin‐resistant bacteria (Lewis 1995), like contemporary reports of methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus parotitis (Nicolasora 2009).

The parotid gland's relative propensity for infection results from physiologic and anatomic factors. Parotid saliva differs from that of the submandibular and sublingual glands. Parotid saliva is predominantly serous compared to the mucinous saliva from the submandibular and sublingual glands. Mucoid saliva contains lysosomes and IgA antibodies, which protect against bacterial infection. Mucins also contain sialic acid, which agglutinates bacteria, thereby preventing its adherence to host tissues. Glycoproteins found in mucins bind epithelial cells, thereby inhibiting bacterial attachment to the epithelial cells of the salivary duct.

Читать дальше