Variants of ABP and Their Etiology

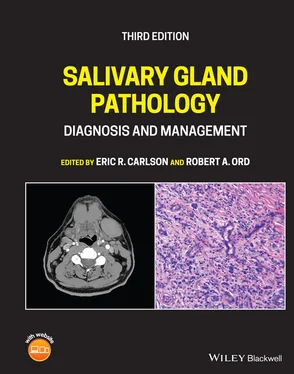

Over the past several decades, changes have occurred in the bacterial flora of the oral cavity that directly reflect the identification of organisms in ABP. In part, this change is evident due to the increased incidence of nosocomial and opportunistic infections in patients who are immunocompromised as well as those critically ill patients in hospital intensive care units whose mouths became colonized with microorganisms that were previously only rarely found in the oral cavity ( Figure 3.4). Moreover, improved culturing techniques have permitted the identification of anaerobes that were previously difficult to recover in the microbiology laboratory. Finally, the occasionally indiscriminate use of antibiotics has allowed for the occupation of other organisms in the oral cavity such as Gram negative enteric organisms. Bacterial Darwinism has also occurred such that iatrogenically and genetically altered staphylococcal organisms have developed penicillin resistance.

Acute bacterial parotitis has two well‐defined presentations, hospital acquired ( Figure 3.4) and community acquired ( Figure 3.5) variants. Numerous factors predispose the parotid gland to sialadenitis. Retrograde infection is recognized as the major cause of ABP. Resulting from acute illness, sepsis, trauma, or surgery, depleted intravascular volume may result in diminished salivary flow that in turn diminishes the normal flushing action of saliva as it passes through Stensen duct. Patients with salivary secretions of modest flow rates show bacteria at the duct papillae and in cannulated ducts, while patients with salivary secretions of high rates show bacteria at the duct papillae but not within the duct (Katz et al. 1990). In a healthy state, fibronectin exists in high concentrations within parotid saliva, which promotes the adherence of Streptococcus species and Staphylococcus aureus around the ductal orifice of the Stensen duct (Katz et al. 1990). Low levels of fibronectin such as those occuring in the unhealthy host are known to promote the adherence of Pseudomonas and Escherichia coli . This observation explains the clinical situation whereby colonization resulting from dehydration leads to a Gram positive sialadenitis in ABP compared to the development of Gram negative sialadenitis of the parotid gland in immunocompromised patients (Miloro and Goldberg 2002). Depending on the health of the host, therefore, specific colonized bacteria can infect the parotid gland in a retrograde fashion. Hospital acquired ABP still shows cultures of Staphylococcus aureus in over 50% of cases (Goldberg and Bevilacqua 1995). Methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus should be ruled out in this population of inpatients. Critically ill and immunocompromised inpatients may also show Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, Escherichia coli, Proteus, Eikenella corrodens, Haemophilus influenzae, Prevotella and Fusobacterium species. Postoperative parotitis has been reported from 1 to 15 weeks following surgery, but most commonly occurs within 2 weeks after surgery (McQuone 1999). The peak incidence of this disease seems to be between postoperative days 5 and 7.

Community acquired ABP is diagnosed five times more commonly than hospital acquired ABP and is diagnosed in emergency departments, offices, and outpatient clinics. This variant of ABP is most commonly associated with staphylococcal and streptococcal species. As community acquired methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus becomes more common in society, this organism will become more prevalent in community acquired ABP. Etiologic factors in community acquired ABP include medications that decrease salivary flow, trauma to Stensen duct, cheek biting, toothbrush trauma, trumpet blower's syndrome and medical conditions such as diabetes, malnutrition, and dehydration from acute or chronic gastrointestinal disorders with loss of intravascular volume. Sialoliths present in Stensen duct with retrograde infection are less common than in Wharton duct, but this possibility should also be considered in the patient with community acquired ABP.

Diagnosis of Acute Bacterial Parotitis

Diagnosis of ABP requires a thorough history and physical examination followed by laboratory and radiographic corroboration of the clinical diagnosis. Whether occurring in outpatient or inpatient arenas, a history of use of anti‐sialogogue medications, dehydration, malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, surgery, or systemic disease supports this diagnosis. A predilection for males exists for ABP, and the average age at presentation is 60 years (Miloro and Goldberg 2002). A systemic disorder will result in both glands being affected, but when one gland is affected, the right gland seems to be involved more commonly than the left gland (Miloro and Goldberg 2002). The declaration of acute requires that the parotitis has been present for one month or shorter.

The classic symptoms include an abrupt history of painful swelling of the parotid region, typically when eating. The physical findings are commonly dramatic, with parotid enlargement, often displacing the ear lobe, and tenderness to palpation. If the Stensen duct is patent, milking the gland may produce pus ( Figures 3.4and 3.5). A comparison of salivary flow should be performed by also examining the contralateral parotid gland as well as the bilateral submandibular glands. The identification of pus should alert the clinician to the need to obtain a sterile culture and sensitivity. Constitutional symptoms may be present, including fever and chills, and temperature elevation may exist provided the gland is infected. If glandular obstruction is present without infection, temperature elevation may not be present. Laboratory values will show a leukocytosis with a bandemia in the presence of true bacterial infection, with elevated hematocrit, blood urea nitrogen, and urine specific gravity if the patient is dehydrated. Electrolyte determinations should be performed in this patient population, particularly in inpatients and outpatients who are malnourished. Probing of Stensen duct is considered contraindicated in ABP. The concern is for pushing purulent material proximally in the gland, although an argument exists that probing may relieve duct strictures and mucous plugging.

The radiographic assessment of ABP is discussed in detail in Chapter 2. Briefly, plain films are of importance to rule out sialoliths, and special imaging studies may be indicated to further image the parotid gland depending on the magnitude of the swelling and the patient's signs and symptoms ( Figure 3.7). The presence of an intraparotid abscess on special imaging studies, for example, may direct the clinician to the need for expedient incision and drainage.

Treatment of Acute Bacterial Parotitis

The treatment of ABP is a function of the setting in which ABP is diagnosed, as well as the severity of the disease within the parotid gland and the presence of medical comorbidities ( Figure 3.8). In the outpatient setting, the presence or absence of pus will assist in directing specific therapy. The presence of pus should result in culture and sensitivity. Early species‐specific antibiotic therapy is the sine qua non of treatment of ABP. Empiric antibiotic therapy should be based on a Gram stain of ductal exudates. In general terms, an anti‐staphylococcal penicillin or a first‐generation cephalosporin is a proper choice. Antibiotics should be changed if cultures and sensitivities show methicillin‐resistant staphylococcal species, in which case clindamycin is indicated in community acquired ABP. In the absence of pus, empiric antibiotic therapy should be instituted as described above. Antibiotic compliance is often difficult for patients such that once or twice daily antibiotics are always preferable. In all patients with community acquired ABP, other general measures should be followed including the stimulation of salivary flow with digital massage, the use of dry heat, and the use of sour ball candies. Sugarless sour ball candies should be recommended for diabetics or those with impaired glucose tolerance. Some elderly and debilitated outpatients may require admission to the hospital in which case intravenous antibiotic therapy will be instituted and incision and drainage may be required. Alteration of anti‐sialogogue medications should be accomplished as soon as possible. In the outpatient setting, these commonly include urinary incontinence medications, loop diuretics, beta blockers, and antihistamines. Glycemic control in diabetics is beneficial in the control of ABP. Finally, effective control of viral load in HIV‐infected patients is of utmost importance.

Читать дальше