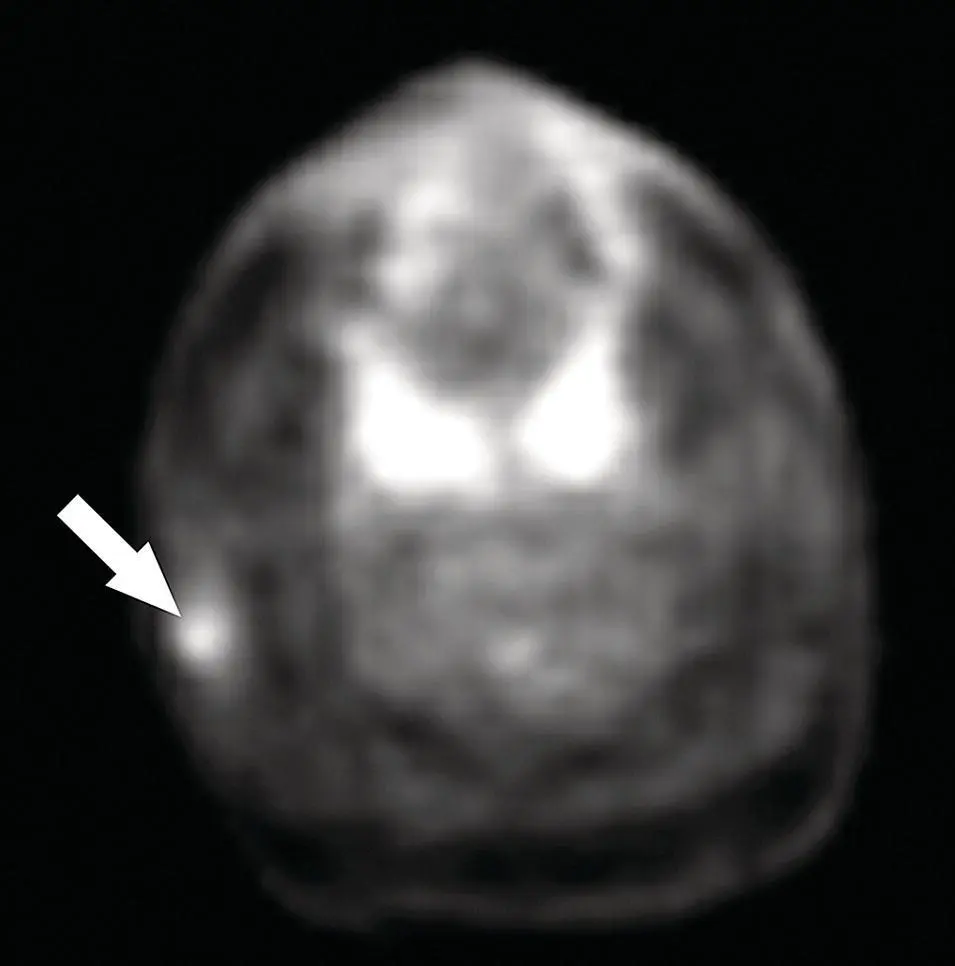

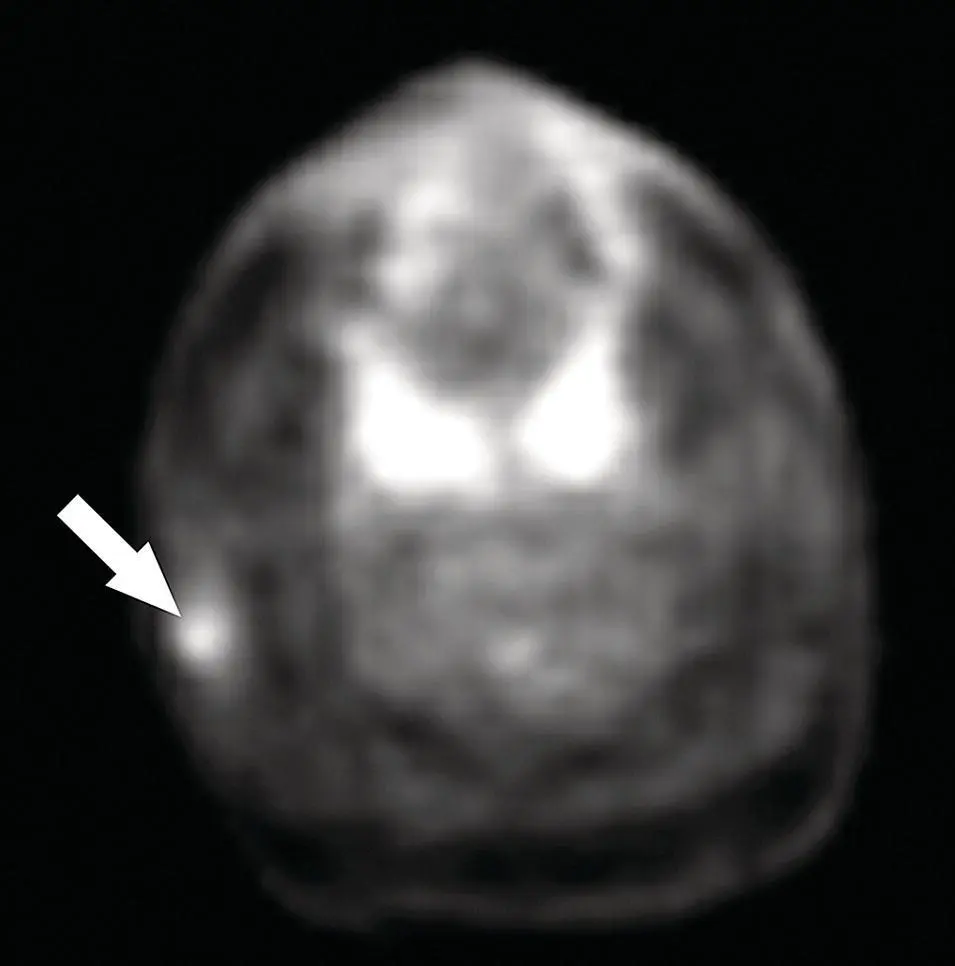

Figure 2.83.Axial PET scan corresponding to the case illustrated in Figure 2.82. The mass in the right parotid gland (arrow) is hypermetabolic. Note two foci of intense uptake corresponding to inflammatory changes in the tonsils.

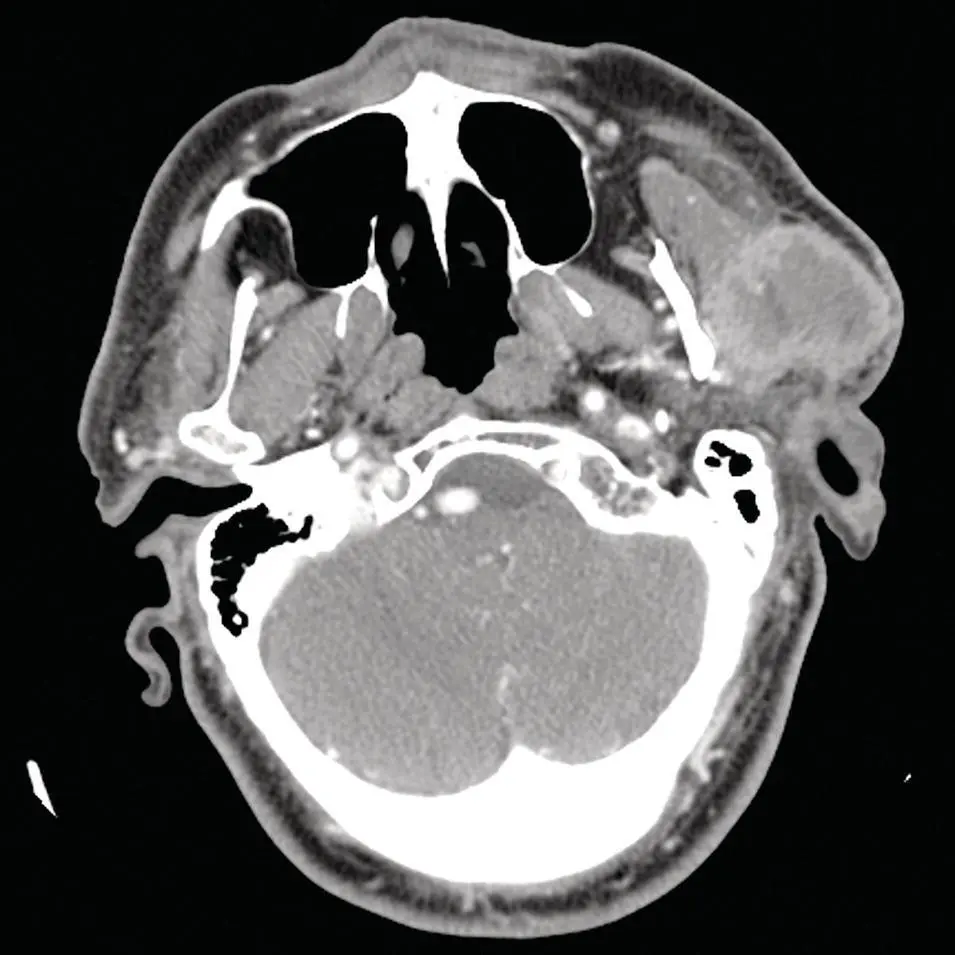

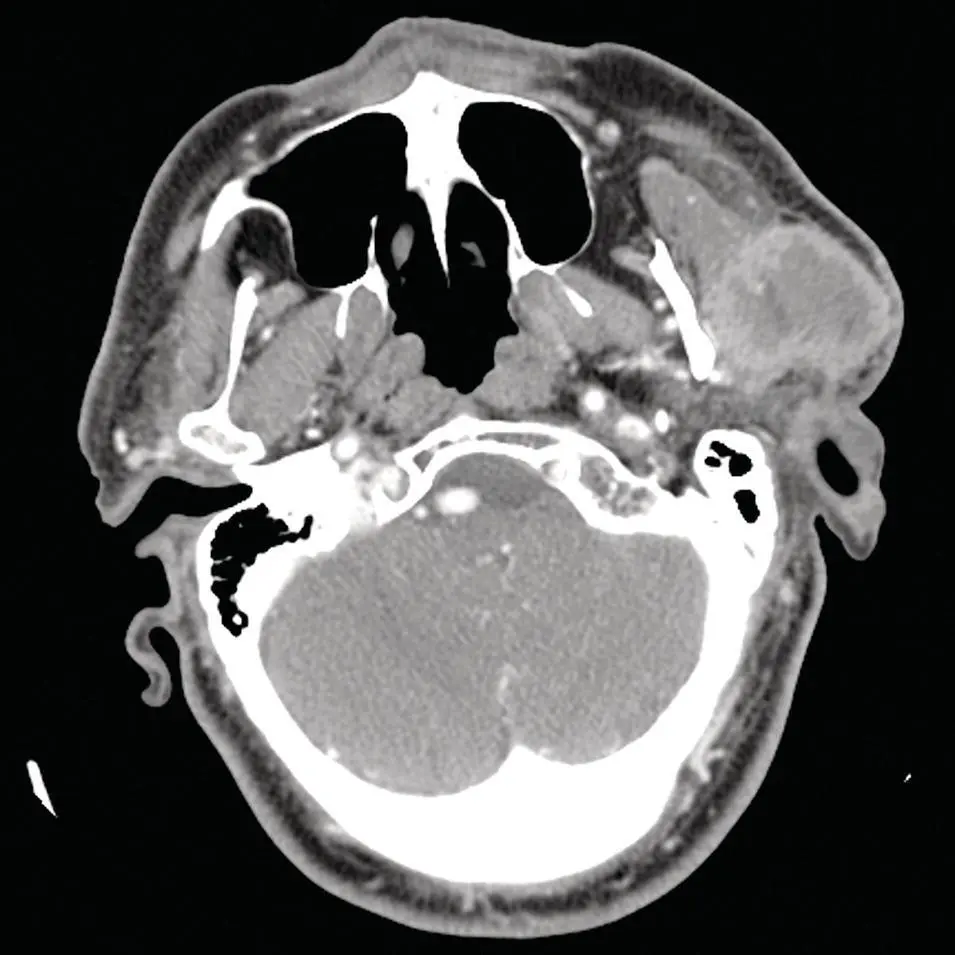

Figure 2.84. Axial contrast‐enhanced CT scan through the parotid glands demonstrating a large mass of heterogenous density and enhancement partially exophytic from the gland. Metastatic squamous cell carcinoma from the scalp was diagnosed.

With either squamous cell carcinoma or melanoma, there is also a concern for perineural invasion and spread. Tumors commonly known to have perineural spread in addition to the above include adenoid cystic carcinoma, lymphoma, and schwannoma. The desmoplastic subtype of melanoma has a predilection for neurotropism (Chang et al. 2004). The perineural spread along the facial nerve in the parotid gland and into the skull base at the stylomastoid foramen must be carefully assessed. MRI with contrast is the best means of evaluating the skull base foramina for perineural invasion. Gadolinium contrast‐enhanced T1 MRI in the coronal plane provides optimal view of the skull base (Chang et al. 2004). There may also be symptomatic facial nerve involvement with lymphadenopathy from severe infectious adenopathy, or inflammatory diseases such as sarcoidosis.

Among the choices for imaging of the salivary glands, CT with IV contrast is the most commonly performed procedure. Coronal and sagittal reformatted images provide excellent evaluation soft tissues in orthogonal planes. The latest generation MDCT scanners provide rapid image acquisition, reducing motion artifact and produce exquisite multiplanar reformatted images.

US has the inherent limitation of being operator dependent, poor at assessing deep lobe of the parotid gland, and surveying the neck for lymphadenopathy, as well as time consuming relative to the latest generation MDCT scanners.

MRI should not be used as a primary imaging modality but reserved for special situations, such as assessment of the skull base for perineural spread of tumors. Although MRI provides similar information to CT, it is more susceptible to motion and has longer image acquisition time but has better soft‐tissue delineation.

PET/CT can also be utilized for initial diagnosis and staging but excels in localizing recurrent disease in postsurgical or radiation fields. Its limitations are specificity, as inflammatory diseases and some benign lesions can mimic malignant neoplasms, and malignant lesions such as adenoid cystic carcinoma may not demonstrate significantly increased uptake of FDG. A major benefit is its ability to perform combined anatomic and functional evaluation of the head and neck as well as upper and lower torso in the same setting. The serial acquisitions are fused to provide a direct anatomic correlate to a focus of radiotracer uptake.

Newer MRI techniques such as dynamic contrast enhancement, MR sialography, diffusion weighted imaging, MR spectroscopy, and MR microscopy are challenging PET/CT in functional evaluation of salivary gland disease and delineation of benign versus malignant tumors. However, PET/CT with novel tracers may repel this challenge.

Conventional radionuclide scintigraphic imaging has largely been displaced. However, conventional scintigraphy with 99mTc‐pertechnetate can be useful for the evaluation of masses suspected to be Warthin tumors or oncocytomas, which accumulate the tracer and retain it after washout of the normal gland with acid stimulants. The advent of SPECT/CT in a similar manner to PET/CT may breathe new life into older scintigraphic exams.

Radiology continues to provide a very significant contribution to clinicians and surgeons in the diagnosis, staging, and post‐therapy follow‐up of disease. Because of the complex anatomy of the head and neck, imaging is even more important in evaluation of diseases affecting this region. The anatomic and functional imaging, as well as the direct fusion of data from these methods, has had a beneficial effect on disease treatment and outcome. A close working relationship is important between radiologists, pathologists, and surgeons to achieve these goals.

Case Presentation – Duplicity

A 58‐year‐old patient ( Figure 2.85a–c) was referred regarding swelling of the left face. The patient's history of present illness included six weeks of a painless left facial swelling, and no associated fever or weight loss.

Hypertension treated with metoprolol and quinapril

Hypercholesterolemia treated with simvastatin

Type 2 diabetes treated with Metformin

The patient is a smoker and has accumulated a 40‐pack year history of cigarette smoking

The patient demonstrated an obvious mass of the left parotid region. There was no tenderness to palpation of the mass. There was no palpable mass of the right parotid gland. Cranial nerve VII was intact. Saliva was present at the left Stensen duct. There were no oral mucosal lesions and no oropharyngeal mucosal lesions.

The patient had undergone a CT scan of the maxillofacial region prior to referral that identified multicentric enhancing masses of the left parotid gland ( Figure 2.85d–f) and a smaller mass of the right parotid gland ( Figure 2.85g). The patient underwent fine needle aspiration biopsy of his largest left parotid mass that demonstrated an oncocytic proliferation.

With a preoperative clinical diagnosis of synchronous, multicentric bilateral Warthin tumors, the patient underwent staged superficial parotidectomies beginning with the larger tumors in the left parotid gland. With a modified Blair incision ( Figure 2.85h), the patient underwent left superficial parotidectomy that began with the identification of the parotid capsule ( Figure 2.85i). The main trunk of the facial nerve was identified and preserved with superficial elevation of the specimen ( Figure 2.85j). The specimen was delivered ( Figure 2.85k and l). Two Warthin tumors were later diagnosed in the specimen on permanent sections ( Figure 2.85m). The resultant tissue bed and facial nerve dissection is appreciated ( Figure 2.85n). At five months following left superficial parotidectomy, the patient was prepared for right superficial parotidectomy ( Figure 2.85o–q). His facial nerve was intact bilaterally. He underwent repeat CT scanning ( Figure 2.85g) that demonstrated one tumor in the superficial lobe of the right parotid gland ( Figure 2.85r–t) that was larger than that noted on the initial CT scan obtained five months earlier. He underwent right superficial parotidectomy with identification and preservation of the facial nerve ( Figure 2.85u–x). Final pathology confirmed the presence of one Warthin tumor ( Figure 2.85y). The patient's postoperative course was unremarkable and he sustained no morbidity with either surgical procedure.

1 Warthin tumors should be suspected when patients present with multicentric unilateral and/or bilateral tumors of the parotid glands.

2 Staging the performance of the bilateral superficial parotidectomies is prudent to avoid the possibility of bilateral facial nerve palsies if bilateral surgery was performed synchronously and postoperative facial nerve weaknesses were noted bilaterally.

Читать дальше