1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...16 The principle of autonomy is critically important in pain care for both the provider and the patient. It is easy to fall into a pattern of issuing instructions to patients in the belief that this is time efficient. This does not respect a patient's autonomy and may not result in a treatment plan that respects the patient's inclinations and healthcare beliefs. Motivational interviewingand shared decision‐makingbring autonomy appropriately into the pain‐focused clinical encounter ( Chapter 14).

The practice of pain care is a continual, pragmatic study of distributive justice. This is because pain medications are viewed as expedient, providing inexpensive pain relief albeit producing cognitive dysfunction, constipation, sedation, abuse risks, and other side effects. In counterpoise with medication risks and benefits, is the substantive investment of time, energy, and moneyrequired to implement most non‐pharmacological strategies. It is a principle of distributive justice that patients should not be exposed to more medical risk than necessary while balancing the costs to society. Why do we still prescribe potentially harmful pain medications when a short course of physical or cognitive therapy would be equally efficacious?

Medical tradition teaches that there were two Pillars at Delphi inscribed with simple but indispensable guidance: Know thyself, and Know thy limits. All too often, we find ourselves stretching to meet the demands of our patients for better, faster, and less expensive solutions. We may be tempted to perform procedures that we don't know well or try treatments that we don't completely understand. While it is laudable to relieve pain as expeditiously as possible, safetyis always the first concern. Clinical practice should never overstep the scope of training. Perform a procedure or prescribe a treatment only if you are (i) can perform it with technical proficiency, and (ii) can manage the complications, common and less so. If not trained to recognize and manage the complications of any therapy, interventional, opioid‐based, or even NSAIDs, one must refrain from intervening. Unfortunately, not treating pain also carries burdens: patients can despair of improved circumstances. There are many pain clinics and always more options for treatment of pain, do not destroy hope. Provide a referral if you cannot act. It is ethical to sustain a patient's hope that pain relief or at least pain mitigation is a reasonable goal.

Finally, pain care offers opportunities to work with patients to advance a sense of self‐efficacyand personal accomplishment. The best outcome is engaging with a patient to identify appealing lifestyle changes and active non‐pharmacological steps that correct a long‐standing pain condition. The opportunity to celebrate these victories with our patients is the true reward of the committed and ethical practice of pain care.

1 Baker, D. (2017). The Joint Commission’s Pain Standards: Origins and Evolution. Oak Brook, IL: The Joint Commission.

2 Beauchamp, T. and Childress, J. (2013). Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 7e. New York: Oxford University Press.

3 Giordano, J. (2006). Moral agency in pain medicine: philosophy, practice and virtue. Pain Physician 9 (1): 41–46.

4 Joint Commission (2012). Safe use of opioids in hospitals. The Joint Commission Sentinel Event Alert 49: 1–5.

6 Advanced skillfulness in clinical practice: The big challenges

Perhaps the biggest challenge in pain care is recognizing a pain problem when it presents in a manner that is atypical. Because common pain‐associated conditions sometimes present in atypical ways and uncommon pain‐associated conditions drive surprisingly more healthcare utilization than might otherwise reflect their prevalence, diagnostic challenges in pain medicine are not uncommon.

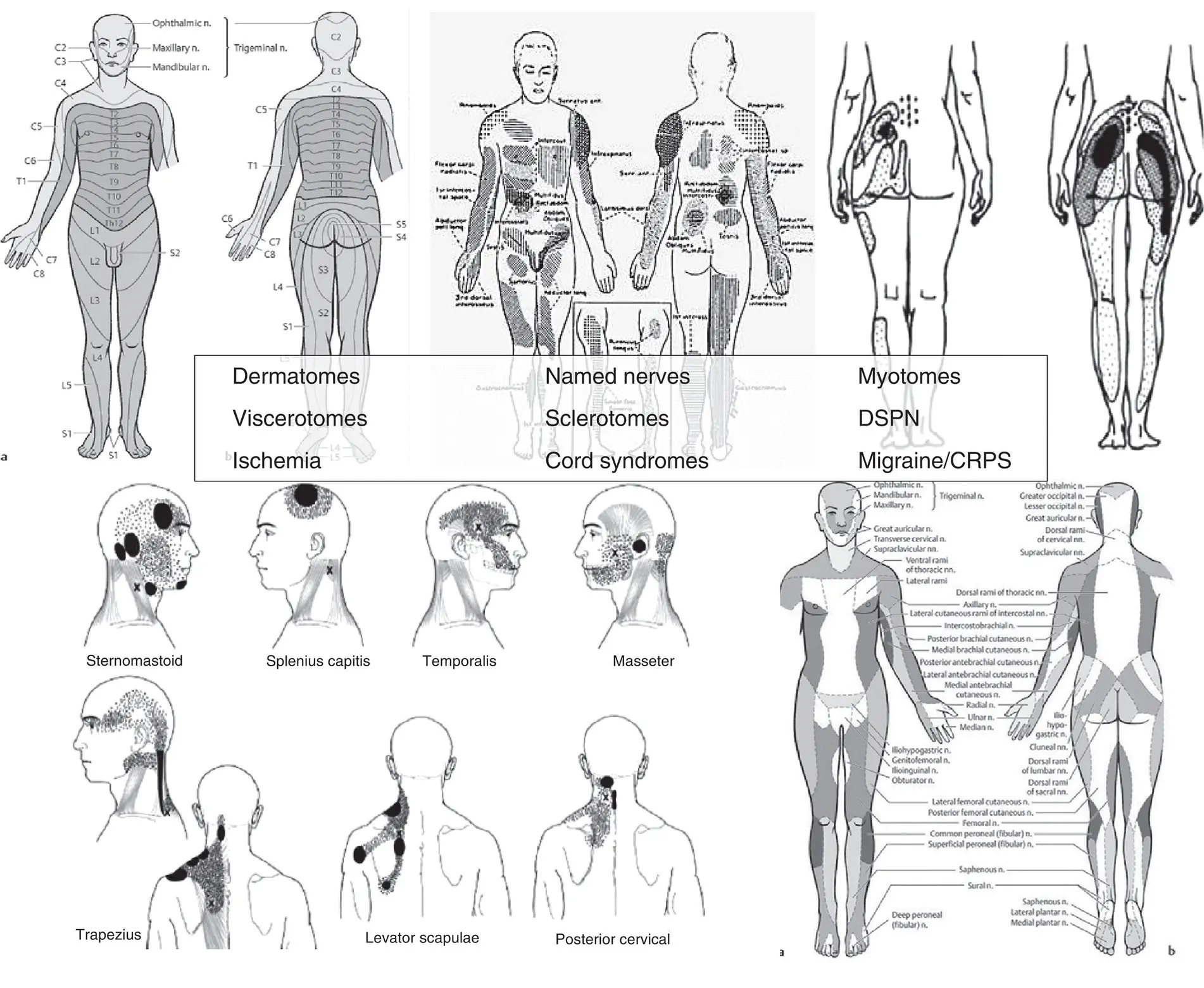

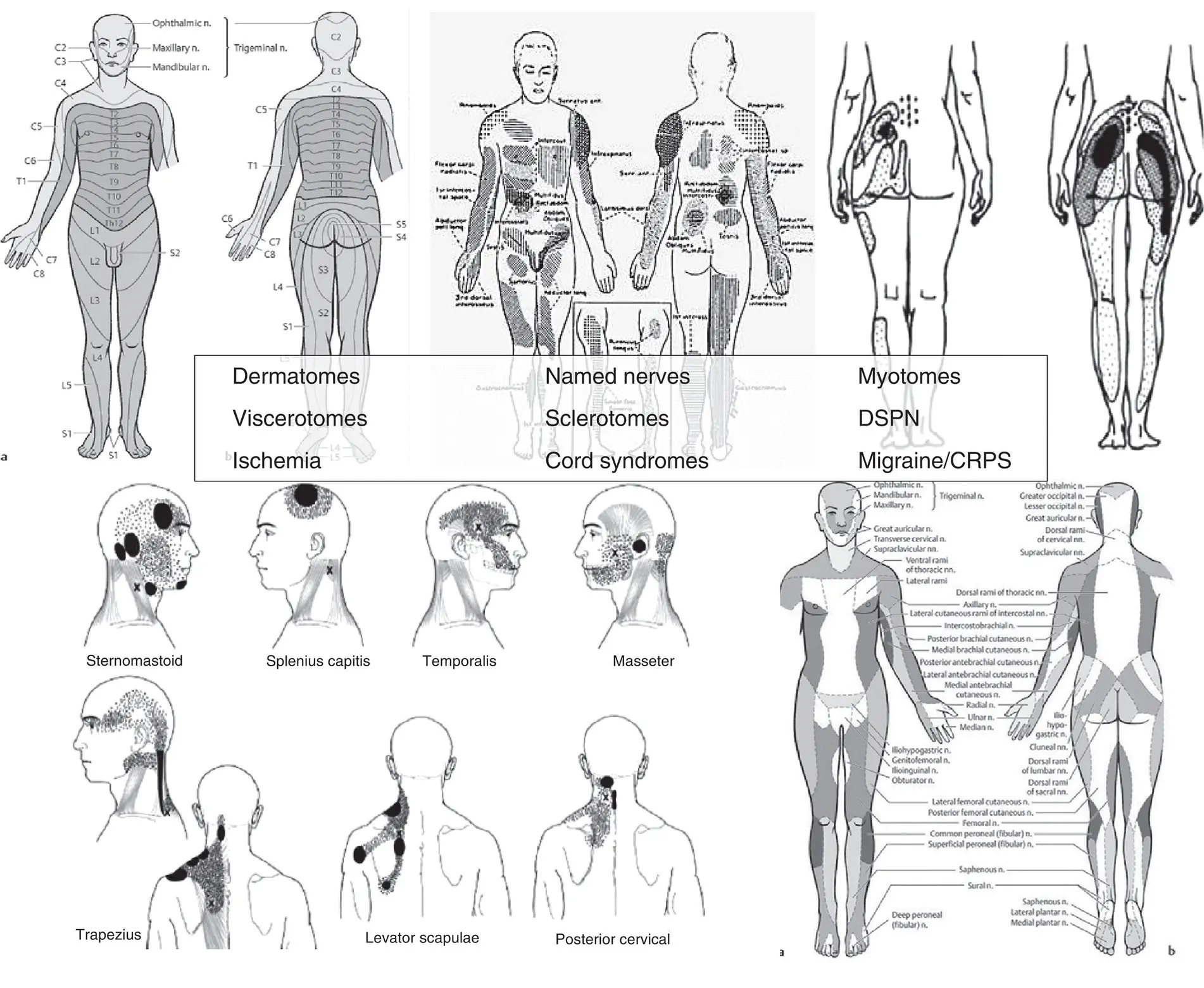

Patternrecognition is a diagnostic method commonly employed by experts, for this reason, and because pain‐conditions often have characteristic “patterns,” it is very helpful to learn some of the major pain patterns ( Figure 6.1). Some are “referred pain patterns.” A referral pattern is the perception of pain in one part of the body in response to nociceptive signaling in another part. Referred paincharacteristically results in pain being perceived in an unharmed part of the body. This can present a diagnostic challenge. A classic example is cardiac pain referring to the left arm or jaw. Another classic pattern is the association of foot, ankle, or leg pain with disease of the lumbar spine. This may be unknown to the public but should be known to healthcare providers. What is less well appreciated is that each major system in the body, including viscera, muscles, bones, as well as nerves, has a characteristic referral pattern. Other classic examples include the referral of pancreatic pain to the mid‐back; and renal pain to the flank or scrotum. Intriguingly, esophageal pain is generally well localized, whereas injury to the uterine cervix produces diffuse pelvic pain. Collectively, the referral patterns of pain perceived from visceral ailments is called the “viscerotome.” Less well known are the patterns of myotomes(muscle pain‐referral patterns) and sclerotomes(bone pain‐referral patterns) (Bähr and Frotscher 1998). Thus, an important challenge in pain medicine is recognizing the diverse presentations of pain‐associated conditions. Often so‐called “non‐anatomical” pain has a biological basis; it simply has not been recognized by the provider. The pictures in Figure 6.1, illustrate some examples of different, anatomical, pain patterns: dermatomes, viscerotomes, myotomes, sclerotomes, diffuse neuropathy, and named nerve patterns. But this catalogue of pain patterns is not exhaustive: still other patterns will be seen with conditions of vascular ischemia or specific pain syndromes such as migraine and chronic regional pain syndrome. Finally, local space occupying lesions can produce bizarre patterns of pain perception, as can neuropathic diseases like multiple sclerosis, transverse myelitis, chronic regional pain syndrome (CPRS), and peripheral neuropathy.

Figure 6.1 Pain patterns, examples. Pain can present with many different patterns, recognizing these is helpful to guiding diagnosis and treatment.

Another critical challenge in pain is: what the pain feels like, known as qualitative featuresor internal experience ( Figure 6.2). In this respect, neuropathic pain is the great imitator of modern pain medicine. It is possible for an injured nerve to reproduce a wide variety of ordinary perceptions: burning, cold, and stabbing, as well as produce sensations that are completely bizarre: searing cold, painful numbness, swollen dullness, tingling cascades running down the back, crawling “ants” underneath the skin, and shocking pain so strong it causes the leg to buckle. All of these sensations may arise as the result of nerve damage or dysfunction in a person who, though perhaps somatically‐focused, is not otherwise prone to thought disorders or delusions. The distress that a person experiences in trying to describe these troubling sensations, or obtain validation within the context of the medical model, is quite real and reasonable.

Читать дальше