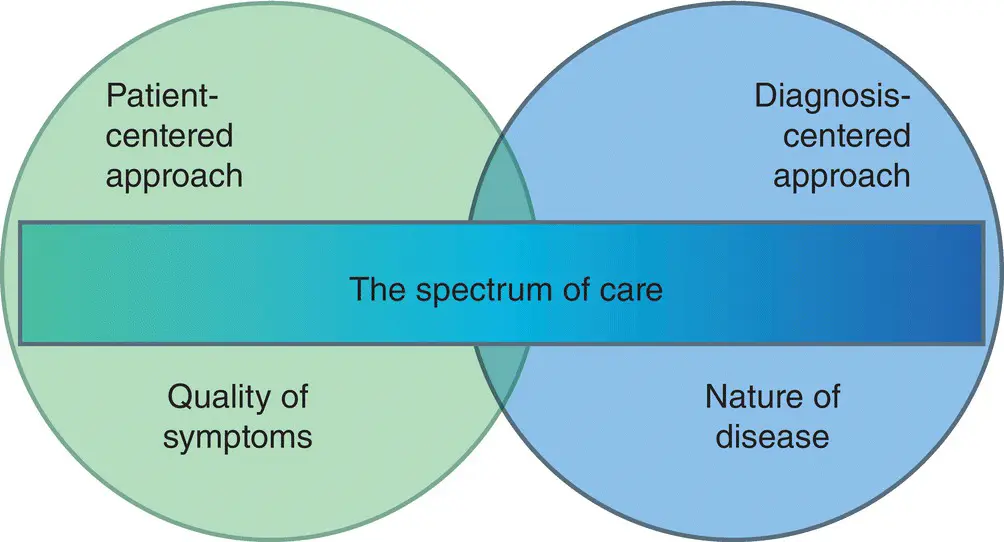

Patient‐centered care vs. disease‐centered care

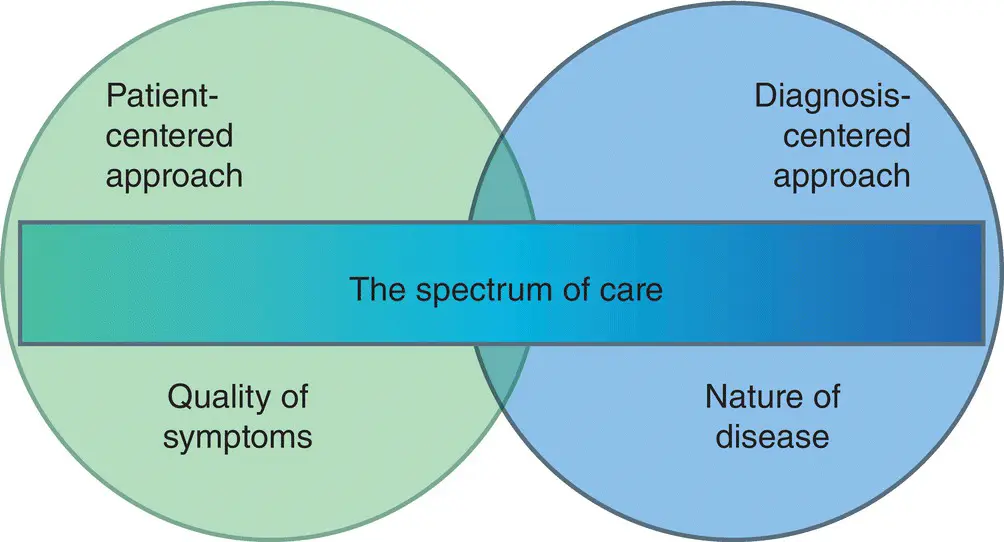

The best pain care balances the needs of the individual patient for pain relief and functional restoration with the providers clinical (disease‐specific) knowledge and expectations for healing and recovery (Frankel 2004) ( Figure 8.3). This model is related to the parallel pathway model above but highlights that the development of therapeutic approaches needs to incorporate the patient's values and needs, as well as the diagnostic “realities” (Agarwal and Murinson 2012).

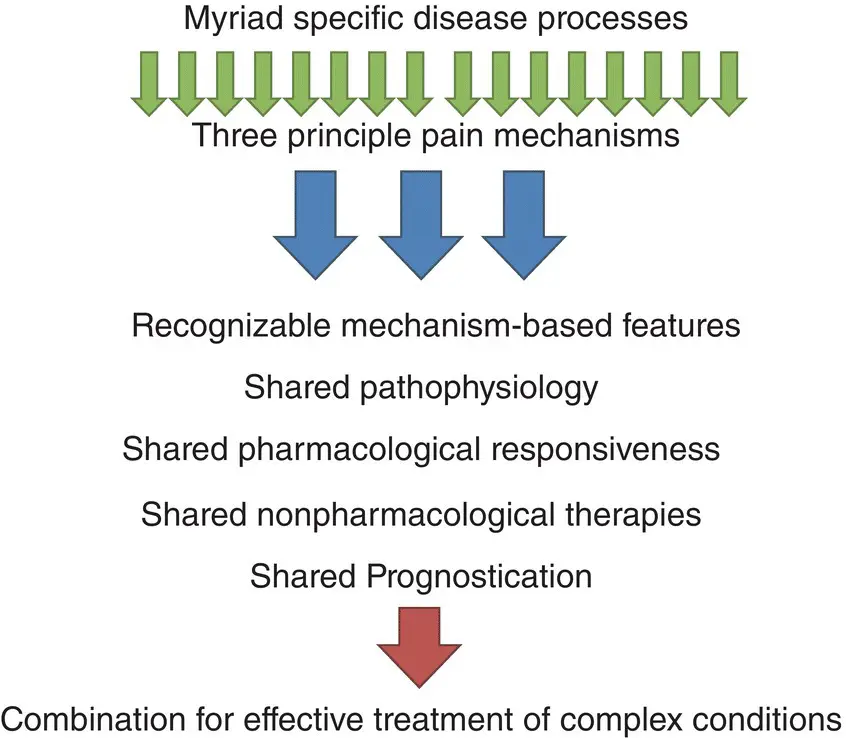

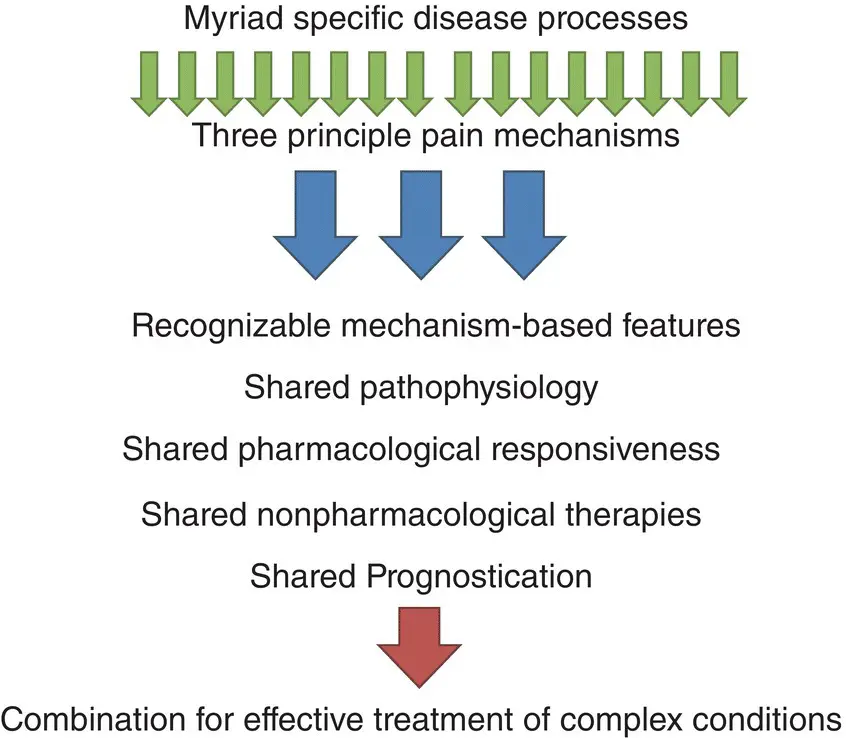

Figure 8.2 Mechanism‐based classification of pain overview: rationale for development and how to apply the model.

Figure 8.3 Balancing knowledge of disease with patient‐centered understanding.

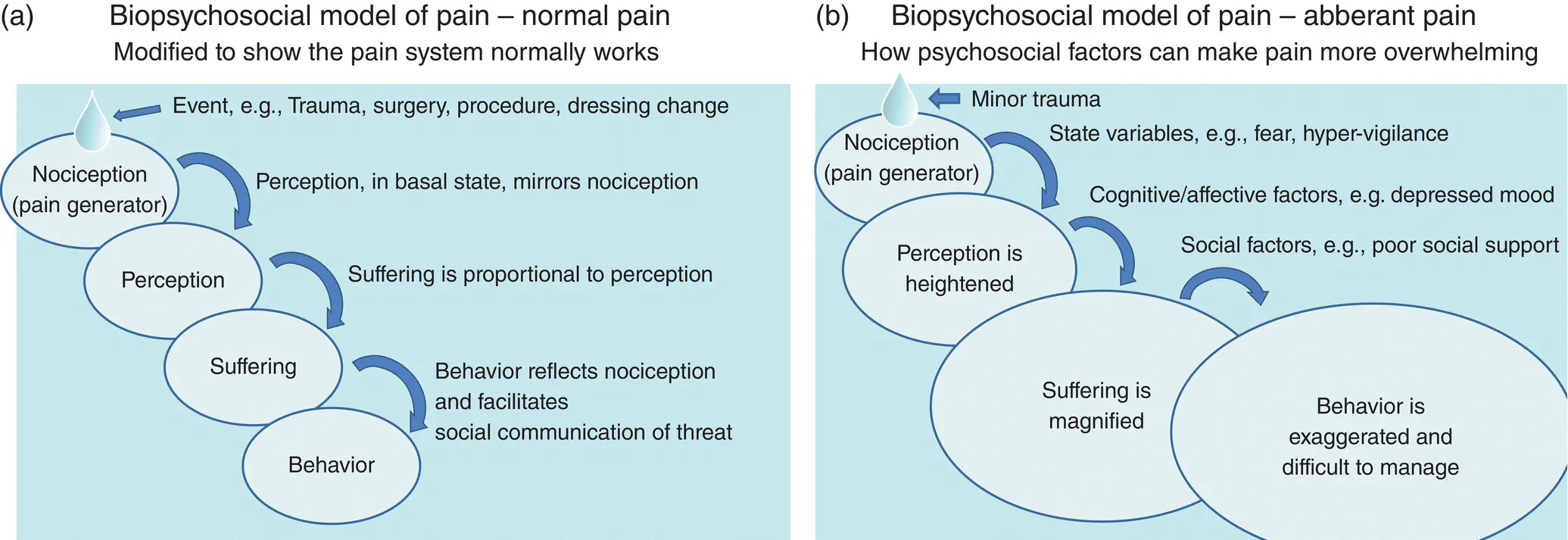

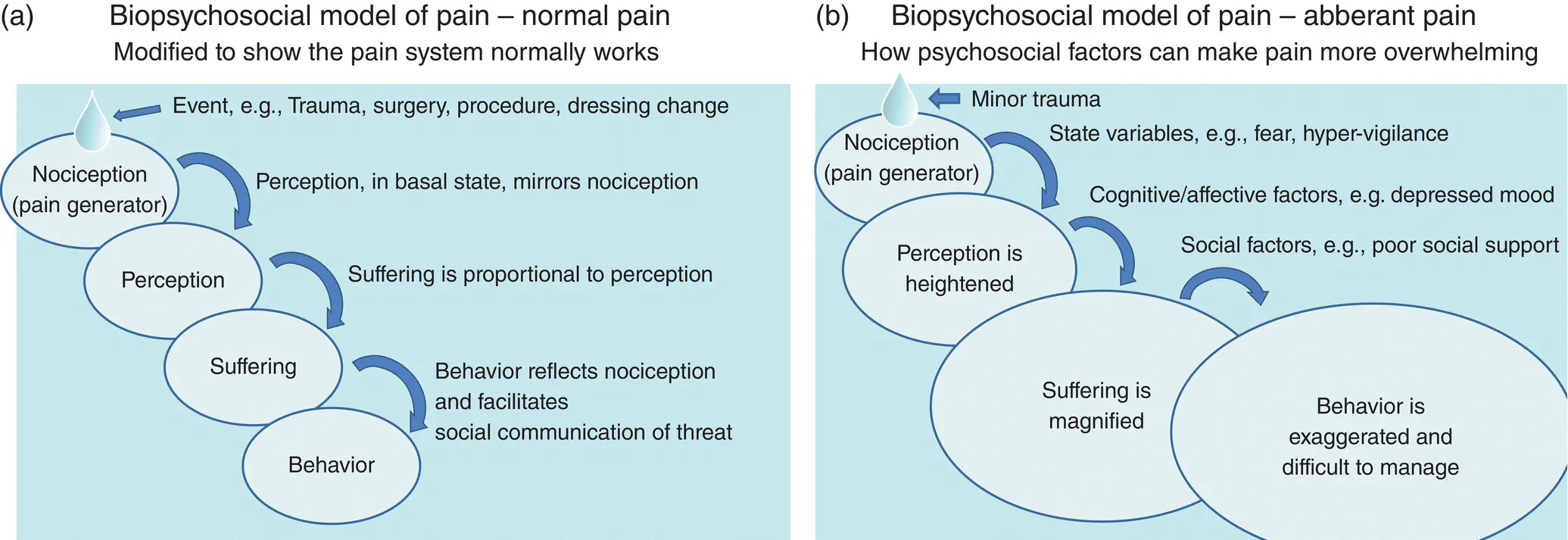

The biopsychosocial model highlights the importance of understanding the patient's psychological and social context which can amplify or diminish pain (Loeser 1982). Like expanding ripples in a pond, dramatic perturbations can arise if frustration builds upon depression upon social isolation to create overwhelming difficulties for the patient who lacks the resources to effectively self‐manage pain and pain‐related affect ( Figure 8.4).

Figure 8.4 (a) Normal functioning demonstrating processes of eudynia; (b) Amplification of pain behavior is a multi‐step process (maldynia), this is often associated with the development of chronic pain ( Chapter 29).

Source: Adapted from Loeser (1982).

It is in the setting of persistentor chronicpain that the biopsychosocial model of pain moves to the foreground. The classic scenario is the patient who has been to 20 doctors, takes 12 different medications, relies on pills to start their day and lives from injection to injection. This patient's behavior is dominated by “pain” and their life is ruined in the process.

It is helpful to first examine the case of “normal pain‐sensing” or eudynia. Eudyniais pain‐sensing as a normal function of the nervous system, it is more common than aberrant pain signaling, sometimes termed “ maldynia.” In eudynia, nociception (primary nociceptive signal transduction) mirrors the degree of injury and is important to ensure survival, Figure 8.2. Each nociception event is mirrored accurately by a perception event. Perceptionis the conscious awareness of pain mediated by the cerebral cortex and leads a person to recognize the potential for injury. The perception of pain is also associated with suffering. This affective component of pain, subserved primarily by medial brain structures, such as cingulate cortex, has intrinsic survival value, prompting protective action against further injury. These affective brain centers are tightly linked with learning circuits, causing the organism to remember and avoid potentially injurious settings. The next and final link in the model is behavior. In normal pain‐sensing, behavior mirrors suffering which mirrors perception which mirrors nociception. In eudynia, pain behaviorserves a useful social purpose of communicatinga person's pain to those around him or her and is a highly efficient way to solicit help. For example, a child at play falls down and is unharmed, the person watching the child might be alarmed by the fall but immediately recognizes that the child is not crying and must be fine. A scraped knee or broken bone produce various forms of pain behavior that quickly convey the need for attention and aid.

The system breaks down when chronic pain affects a patient with a perturbed psychological state, disrupted mood, and dysfunctional social support network. Minor nociception is amplified by negative cognitions to a more threatening experience of pain, this in the context of depressed mood leads to amplified suffering, and this, in the absence of adequate social supports leads to aberrant behaviorwhich disturbs the patient and disrupts those around them. It is impossible to unwind this complex type of pain without coordinated support and collaboration of multiple professionals, all proficient in pain, Chapter 16.

1 Agarwal, A.K. and Murinson, B.B. (2012). New dimensions in patient‐physician interaction: values, autonomy, and medical information in the patient‐centered clinical encounter. Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal 3 (3): e0017.

2 Frankel, R.M. (2004). Relationship‐centered care and the patient‐physician relationship. Journal of General Internal Medicine 19 (11): 1163–1165.

3 Loeser, J. (1982). Concepts of pain. In: Chronic Low‐Back Pain (eds. M. Stanton‐Hicks and R. Boas), 145–148. New York: Raven Press.

4 Murinson, B.B., Agarwal, A.K., and Haythornthwaite, J.A. (2008). Cognitive expertise, emotional development, and reflective capacity: clinical skills for improved pain care. The Journal of Pain 9 (11): 975–983.

9 The pain‐focused clinical history: well‐developed illness narratives impact pain outcomes

History‐taking for the patient with acute pain can focus on eliciting relevant details with empathy and compassion. To build a more durable relationship with patients in persistent pain, it is essential to honor the pain narrativeby starting with open questions, such as: “tell me how your pain began.” It is precisely the patient who has told their story many times who will be most impressed by your willingness to listen attentively. In truth, the diagnostic process begins with an illness narrative, embedded there you find the cardinal featuresof the pain. It is imperative to listen with openness and without interrupting, because this is essential to establishing trust (Frankel and Stein 2001). There will never be another opportunity to lay the correct foundation for a robust therapeutic alliance. Try to suspend disbelief: perhaps the worst experience for someone with pain is to feel disbelieved. People are exquisitely sensitive to the perception that others are not taking their problems seriously. Don't be the one who leaps to a psychological explanation when genuine pain mechanisms are at work. Small fiber neuropathy is one condition that produces disruptive pain with very few clinical signs. Empathetic demeanor and compassionate concern will elicit gratitude from the patient whose diagnosis remains to be determined (Murinson et al. 2008).

In the pain history, the cardinal features include: Quality, Region, Severity, and Timing. It is also helpful to elicit: what is “Usually associated with” the pain, what steps have made the pain “Very much better,” and what has made the pain “Worse,” Table 9.1. Pain severity can be rapidly assessed with a standard scale ( Figure 9.1). It is sometimes necessary to establish the cardinal features of more than one “pain.” For example, patients with headaches often experience multiple headache types; each should be characterized and may require different therapy.

Читать дальше