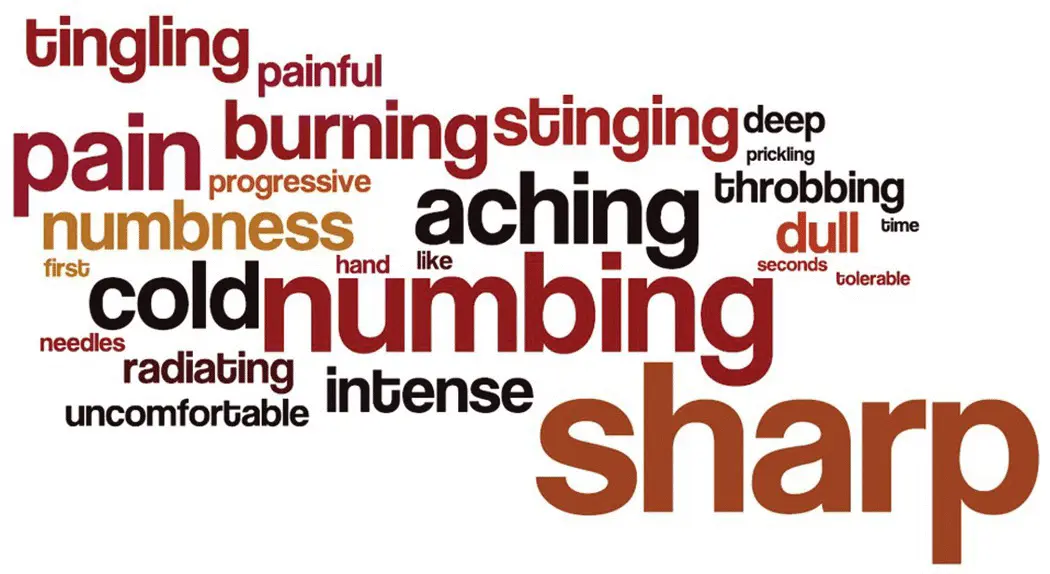

Figure 6.2 Qualities of pain, examples.

The temporal courseof pain is another major challenge in bridging the gap between patient and provider. Sometimes, a person seems to take “too long” to recover from a procedure or trauma. Other times pain seems to flair when stresslevels are elevated. At times, we risk labeling a stressed “slow healer” as a person with “chronic pain.” Other times, there is an unrecognized triggerwhich prompts pain to come and go. One potential cause of profound, intermittent, low back pain is spondylolisthesis. In this disorder, there is an instability of one or more vertebrae. The “typical” experience is terrific pain after arising from being seated on a low support, sometimes getting up from a toilet is the culprit and the patient may be embarrassed. The chronically traumatized disc can become super‐sensitized through the ingrowth of pain‐sensitive (nociceptive) nerve endings making the pain seem atypical (Stefanakis et al. 2012). Skilled physical therapy, chiropractic, analgesia and core muscle strengthening can help reduce minor to moderate spondylolistheses, more severe instabilities may require surgery. Visceral pain‐associated syndromes, e.g. pancreatic, inflammatory bowel disease, and cystitis, are also characterized by a waxing and waning course.

A final challenge is the need to access reliable unbiased informationabout pain medicine diagnoses and treatments. Typically, little time is spent in clinical training on pain. As of 2009, most US medical schools taught only four hours of pain content over four years, this despite the fact that nearly half of patients presenting for medical care have pain of one form or another (Mezei et al. 2011). Not infrequently, providers have trouble determining what's wrong with a “pain patient,” because they were not adequately taught to recognize the problem the patient is describing. Exceptions are that osteopathic medical and physical therapy schools offer advanced trainingin musculoskeletal disorders and fellowship pain training is often excellent but may be focused on procedural management (Watt‐Watson et al. 2009). For many, collaborative interprofessional care is essential. Reliable resources include Biomed plus for patient‐oriented information, UpToDate online, or any of the standard textbooks of pain medicine (Fishman et al. 2009; McMahon et al. 2013; Warfield et al. 2016). Neuromuscular conditions are well characterized online (Pestronk 2017). In short, it is important to learn about common pain‐associated conditions and create a differential diagnosis to guide evaluation and treatment strategies.

1 Bähr, M. and Frotscher, M. (1998). Duus’ Topical Diagnosis in Neurology: Anatomy, Physiology, Signs, Symptoms, 5e. Stuttgart, New York: Thieme.

2 Fishman, S.M., Ballantyne, J.C., and Rathmell, J.P. (2009). Bonica’s Management of Pain (Fishman, Bonica’s Pain Management), 4e. Philadelphia: LWW.

3 McMahon, S., Koltzenburg, M., Tracey, I., and Turk, D. (eds.) (2013). Wall and Melzack’s Textbook of Pain, 6e. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders.

4 Mezei, L., Murinson, B.B., and Johns Hopkins Pain Curriculum Development Team (2011). Pain education in North American medical schools. The Journal of Pain 12 (12): 1199–1208.

5 Pestronk A (2017) (Ed.). Washington University St. Louis Neuromuscular Disease Center. http://neuromuscular.wustl.edu/(accessed 18 December 2017).

6 Stefanakis, M., Al‐Abbasi, M., Harding, I. et al. (2012). Annulus fissures are mechanically and chemically conducive to the ingrowth of nerves and blood vessels. Spine 37 (22): 1883–1891.

7 Warfield, C.A., Bajwa, Z.H., and Wootton, R.J. (2016). Principles and Practice of Pain Medicine, 3e. New York: McGraw‐Hill Education/Medical.

8 Watt‐Watson, J., McGillion, M., Hunter, J. et al. (2009). A survey of prelicensure pain curricula in health science faculties in Canadian universities. Pain Research & Management 14 (6): 439–444.

7 Cognitive factors that influence pain

There are many cognitive influences on pain; some of these lessen pain while others increase it. Several cognitive influences are modifiable and have clinical utility in treating pain. Selected cognitive influences on pain are outlined here.

Cognitive influences that increase pain:

Catastrophizing. Catastrophizing describes maladaptive cognitive patterns in response to challenges, especially: imagining a symptom means something ominous (magnification), focusing on a problem (rumination), and feeling unable to resolve a problem (helplessness). Catastrophizing about pain can amplify pain intensity and suffering and is associated with poorer long‐term outcomes (Quartana et al. 2009). Originally conceptualized by Ellis, catastrophizing has had a great impact on pain research however, large‐scale studies are generally needed to show statistical significance. Clinically, effects of catastrophizing on pain are moderate. Cognitive behavioral therapy can help patients shift negative cognitions and replace defeating “self‐talk” with more positive messages, it is not known whether single interventions are effective, or whether physicians can administer brief interventions (Turk 2003). For patients with chronic pain who catastrophize, clinical psychological evaluation is indicated.

Anxiety. Anxiety facilitates pain perception. The mechanisms of this are not fully established but one study induced acute pain‐associated anxiety which produced increased experimental pain (Rainville et al. 2005). Chronic anxiety is also associated with increased pain in a clinical setting. It is important for healthcare environments to reduce anxiety where possible and ideally providers will create therapeutic relationships sensitive to patients' anxieties. Measures including: reduced jargon, shared decision‐making, and utilizing web interfaces and videos to explain procedures in advance can help reduce anxieties. When anxiety is excessive, it is treated with medication and psychotherapy.

Anger. Anger can increase pain. One study of pain‐related emotions used hypnotic suggestion to modulate the mood of normal volunteers while pain was tested. In those patients for whom anger was induced, there was a significant increase in perceived pain intensity as well as pain‐associated unpleasantness. Anger also has important effects in a clinical setting but the relationship between pain and anger is complex. Studies of patients with low back pain have indicated that the suppression of anger expression increased pain and pain behaviors (Burns et al. 2008). Generally, negative emotions heighten pain while positive emotions reduce pain (Yarns et al. 2020).

Low self‐efficacy. Low self‐efficacy is when a person feels that they can do little to improve their situation. A related concept is called the “external locus of control.” Someone with an external locus of control will feel that their situation is controlled by factors outside themselves. This is contrasted to having an internal locus of control which is when a person feels that they can control their lives and engage in activities that will have a beneficial effect. Patients with internal locus of control have better health‐related outcomes. Physicians can foster self‐efficacy using motivational interviewing techniques: “What are some small steps you could take to start getting control over your pain?.” Many pain self‐management strategies require patients to take active steps, e.g., hotpacks, ice, meditation, and pacing require a commitment from patients.

Читать дальше