1 ...7 8 9 11 12 13 ...37 II

In the middle ages sovereigns, such as the kings of England, frequently borrowed large amounts, thereby relying on the services of Italian bankers. Rulers in the Low Countries did the same, borrowing not only from bankers but also from family members, fellow royalty, noblemen, and towns. 10 However, besides this international system of «high finance» there were other ways to move money around, such as through the issuing of public annuities. Since the thirteenth century towns and villages in much of the Low Countries sold life annuities and redeemable annuities. Life annuities provided the buyer with a pension to be paid for the remainder of his or her life, redeemable annuities had to be paid until the principal was repaid, which was at the discretion of the seller. These annuities emerged in the North of France in the thirteenth century and quickly became a major type of funding in Northwest Europe. 11 They allowed creditors to lend their savings to debtors on the payment of an annual premium that we today would call interest. 12 In the late Middle Ages these became the instrument of choice of public bodies in the Northwest of Europe: in the Low Countries, the North of France, and the German Empire, towns and villages «borrowed» by selling life annuities and redeemable annuities.

Although annuities were important in redistributing of savings, there were other techniques available in the late Middle Ages as well: money was moved around via networks of moneylenders, itinerant merchants used financial techniques such as the bill of exchange, and there emerged early banking institution –such as the Monte dei Paschi di Siena , founded in 1472–. This was also a time of expansion of financial markets: instead of having money lay idle, savers began to invest, causing money to be reallocated in a more efficient way. 13 However, the redistribution of savings was not self-evident, as it could be severely hindered by usury laws, prohibiting the taking of interest, and thus interfering in processes of price making. Initially usury legislation seems to have been quite harsh in the Low Countries. 14 However the introduction of annuities probably gave an impulse to the redistribution of savings because the Church did not regard these as usurious: pope Innocent IV already sanctioned annuities in 1252. 15 Since these instruments obviously allowed for the circumventing of usury laws, some theologians continued to question whether annuities should be allowed. Until the fifteenth century several popes spoke out on the subject; all sanctioned annuities. 16

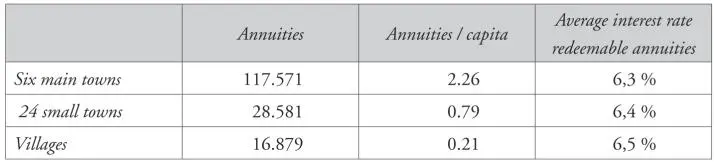

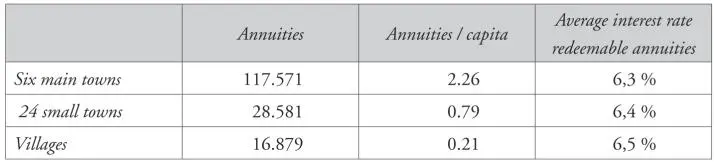

Annuities became a generally accepted financial instrument in the later middle ages. But still, taking high interest rates, even by means of selling annuities, was considered usurious, and authorities sometimes applied price ceilings participants in financial markets were not to exceed. Particularly emperor Charles V (r. 1515-1555) was quite active in this respect, setting the maximum interest rate at 12 % per year in 1540. 17 These maximum interest rates had little effect in practice though, because they were set well above the premiums that were usually paid in financial markets, about 5 % to 6 % for redeemable annuities (table 1) and c. 10 % for life annuities. Thus, the interest rate ceiling did not interfere with pricing.

TABLE 1

Public debt in Holland in 1514 (annuities, in guilders of 20 stuivers)

Source: Informacie , author’s calculations.

Yet, not all public debt was issued through the market: forced loans were not unheard of in the area under investigation here, the Northern Low Countries, where cash-strapped towns occasionally forced wealthy subjects to buy annuities. But based on our sources, it seems that towns only did so in emergency situations. 18 Moreover, a glance at map 2 makes clear that public bodies also sold annuities to foreigners, who could not be forced to buy in any way. It therefore seems that the market was the most important instrument used to create public debt.

So, by the later Middle Ages, in the Low Countries there were only few obstructions to the redistribution of savings through the market. How did towns find savers and negotiate interest rates? To cut costs and reduce risks, they usually preferred to sell annuities to inhabitants and people living nearby. 19 Only when their demand for savings exceeded local supply, they turned to large towns in their surroundings and abroad, using brokers to investigate possibilities to sell annuities. Thus, in 1413 the town government of Leiden met with a broker, who apparently advised them to enter capital markets in Brabant. Next, the town sent representatives to Antwerp to sell annuities. 20 How they proceeded in Antwerp is unknown, but again it seems likely that they made use of the services of local brokers. 21 Representatives of towns usually entered financial markets with a mandate to sell annuities at a certain interest rate, which was probably based on earlier communications with brokers. When they did not manage to sell sufficient annuities at this interest rate they simply could improve their offer. When the government of Leiden found out, in 1472, that demand for life annuities at interest rates of 10 % (one life) and 8,5 % (two lives) was low, it reacted by offering inhabitants of Leiden resp. 11,1 % and 9,1 %. 22 In other instances we also encounter price making: some elderly people looking to buy life annuities from Leiden managed to negotiate higher interest rates –presumably to compensate for their low life expectancy–. 23 A claim by the large village of Noordwijk also hints at the adjustment of interest rates to sell annuities: the village claimed to have offered interest rates as high as 16,7 %, 20 % and even 25 %, but did not manage to find buyers, presumably because of a lack of creditworthiness. 24 Further evidence of price making is presented in figure 2, which will be discussed in more detail later in the text. Towns and villages sold redeemable annuities at interest rates ranging from 4,8 % to 12,5 %, although by far the most were sold in the range of 5,6 % to 6,7 %. 25 This range of interest rates also confirms that sovereigns did not yet impose maximum interest rates at levels that interfered with market prices: there was ample room to negotiate interest rates acceptable to creditors and debtors.

The interest rates presented here are nominal interest rates. They are likely to reflect the risk of inflation and currency manipulation. Apart from this interest rates consist of a) compensation for the time the creditor cannot use the money, b) a premium that reflects the expected increase of overall expected income, and c) a default risk premium. 26 Considering that Holland was in a monetary union with the regions of Flanders, Brabant and Zeeland in this period, the risk of inflation was more or less the same everywhere in large parts of the Low Countries. In theory the default risk premium may have varied from one public body to another: as explained earlier, towns that had earlier defaulted on annuity payments and therefore lacked creditworthiness, had to offer higher interest rates to investors. Their «credit rating» is thus likely to have affected pricing, although it must be added that towns that had reneged usually did not succeed in selling any more annuities, or stopped borrowing altogether. 27

Another element that determined default risk was the institutional framework of financial markets. How much expenses could a creditors expect to make when trying to enforce interest payments from reneging towns? Towns usually secured annuities relying on a community responsibility system that allowed creditors to hold all inhabitants liable for defaults. 28 In theory this may have meant that lending to large towns was less risky than to small towns and villages: the community responsibility system depended on the number of liable subjects frequenting the creditor’s residence. For the latter, the chances of encountering an inhabitant liable for public debt was greater in the event they had invested in the public debt of a large town with a substantial group of itinerant merchants. In practice creditors will therefore have selected debtors based on the probability that they would be able to hold someone liable –hence the relatively limited geographical scope of village debt and the much larger scope of urban debt, an issue that will be discussed further on–.

Читать дальше

![Rafael Gumucio - La edad media [1988-1998]](/books/597614/rafael-gumucio-la-edad-media-1988-1998-thumb.webp)