John O'Brien - Earth Materials

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John O'Brien - Earth Materials» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: unrecognised, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Earth Materials

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Earth Materials: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Earth Materials»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Earth Materials,

Earth Materials,

Earth Materials — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Earth Materials», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The most frequently cited example of ionic bonding is the bonding between sodium (Na +1) and chloride (Cl −1) ions in the mineral halite (NaCl) ( Figure 2.10). As a column 1 (group IA) element, sodium is very metallic and electropositive, with a rather low electronegativity (0.93). Sodium has a strong tendency to give up one electron to achieve a stable electron configuration. On the other hand, chlorine, as a column 17 (group VIIA) element, is very nonmetallic, has a strong affinity for electrons and has a high electronegativity (3.5). It has a strong tendency to gain one electron to achieve a stable electron configuration. When sodium and chlorine atoms bond, the sodium atoms release one electron to become smaller sodium cations (Na +1) with the “stable octet” electron configuration (neon), while the chlorine atoms capture one electron to become larger chloride anions (Cl −1) with “stable octet” electron configurations. As we shall see, the “exchange” is incomplete. The two atoms are then joined together by the electrostatic attraction between particles of opposite charge to form the compound NaCl. In macroscopic mineral specimens of halite, many millions of sodium and chloride ions are bonded together, each by the electrostatic or ionic bond described above. Note that the numbers of chloride anions and sodium cations must be equal if the electric charges are to be balanced so that the mineral is electrically neutral. Other group IA (1) and group VIIA (17) elements bond ionically to produce minerals such as sylvite (KCl).

Ionic bonds also form when group IIA and group VIA elements combine. In the mineral periclase (MgO), magnesium (Mg +2) and oxygen (O −2) ions are bonded together to form MgO. In this case, electropositive, metallic magnesium atoms from group IIA tend to donate two valence electrons to become stable, smaller divalent magnesium cations (Mg +2) while highly electronegative, nonmetallic oxygen atoms from group VIA capture two valence electrons to become stable, larger divalent oxygen anions (O −2). The two oppositely charged ions are then held together by virtue of their opposite charges by an electrostatic or ionic bond. Once again, the number of magnesium cations (Mg +2) and oxygen anions (O −2) in periclase (MgO) must be the same if electrical neutrality is to be conserved. A slightly more complicated example of ionic bonding involves the formation of the mineral fluorite (CaF 2). In this case, electropositive, metallic calcium atoms from class IIA release two electrons to become stable divalent cations (Ca +2). At the same time, two nonmetallic, strongly electronegative fluorine atoms from class VIIA each accept one of these electrons to become stable univalent anions (F −1). Pairs of F −1anions bond to each Ca +2cation to form ionic bonds in electrically neutral fluorite (CaF 2).

In ideal ionic bonds, ions can be modeled as spheres of specific ionic radii in contact with one another ( Figure 2.10), as though they were ping‐pong balls or marbles in contact with each other. This approximates real situations because the attractive force between ions of opposite charge (Coulomb attraction) and the repulsive force (Born repulsion) between the negatively charged electron clouds are balanced when the two ions approximate spheres in contact ( Figure 2.11). If they were moved farther apart, the electrostatic attraction between ions of opposite charge would move them closer together. If they were moved closer together, the repulsive forces between the negatively charged electron clouds would move them farther apart. It is when they behave as approximate spheres in contact that these attractive and repulsive forces are balanced.

Bonding mechanisms play an essential role in contributing to material properties. Crystals with ionic bonds are generally characterized by the following:

1 Variable hardness that increases with increasing electrostatic bonding forces

2 Brittle at room temperatures.

3 Quite soluble in polar substances (such as water).

4 Intermediate melting temperatures.

5 Absorb relatively small amounts of light, producing translucent to transparent minerals with light colors and vitreous to sub‐vitreous luster in macroscopic crystals.

2.3.3 Covalent (electron‐sharing) bonds

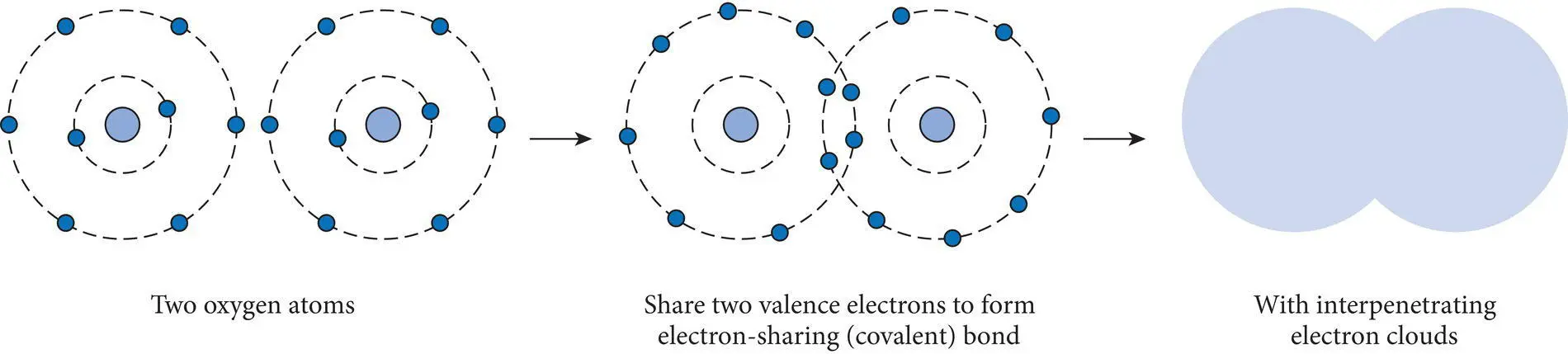

When nonmetallic atoms bond with other nonmetallic atoms they tend to form covalent bonds , also called electron‐sharing bonds. Because the elements involved are highly electronegative they each tend to attract electrons; neither gives them up easily. This is a little bit like a tug‐of‐war in which neither side can be moved so neither side ends up with sole possession of the electrons needed to achieve stable electron configurations. In simple models of covalent bonding, the atoms involved share valence (thus covalent) electrons ( Figure 2.12). By sharing electrons, each atom gains the electrons necessary to achieve a more stable electron configuration in its highest principal quantum level.

Figure 2.11 Relationship between attractive and repulsive forces between ions produces a minimum net force when the near spherical surfaces of the ions are in contact.

Figure 2.12 Covalent bonding in oxygen (O 2) by the sharing of two electrons from each atom.

A relevant nonmineral example is oxygen gas (O 2) molecules. Each oxygen atom from column 16 (group VIA) requires two electrons to achieve a stable electron configuration in its highest principal quantum level. Since both oxygen atoms have an equally large electron affinity and electronegativity, they tend to share two electrons in order to achieve the stable electron configuration. This sharing is modeled as interpenetration or overlapping of the two electron clouds ( Figure 2.12). Interpenetration of electron clouds due to the sharing of valence electrons forms a strong covalent or electron‐sharing bond. Because the bonds are localized in the region where the electrons are “shared” each atom has a larger probability of electrons in the area of the bond than it does elsewhere in its electron cloud. This causes each atom to become electrically polarized with a more negative charge in the vicinity of the bond and a less negative charge away from the bond. Polarization of atoms during covalent bonding is accentuated when covalent bonds form between different atoms with different electronegativities. This causes the electrons to be more tightly held by the more electronegative atom which in turn distorts the shape of the atoms so that they cannot be as effectively modeled as spheres in contact.

Other diatomic gases with covalent bonding mechanisms similar to oxygen include the column 17 (group VIIA) gases chlorine (Cl 2), fluorine (F 2), and iodine (I 2) in which single electrons are shared between the two atoms to achieve a stable electron configuration. Another gas that possesses covalent bonds is nitrogen (N 2) from column 15 (group V) where three electrons from each atom are shared to achieve a stable electron configuration. Nitrogen is the most abundant gas (>79% of the total) in Earth's lower atmosphere. In part because the two atoms in nitrogen and oxygen gas are held together by strong electron‐sharing bonds that yield stable electron configurations, these two molecules are the most abundant constituents of Earth's lower atmosphere.

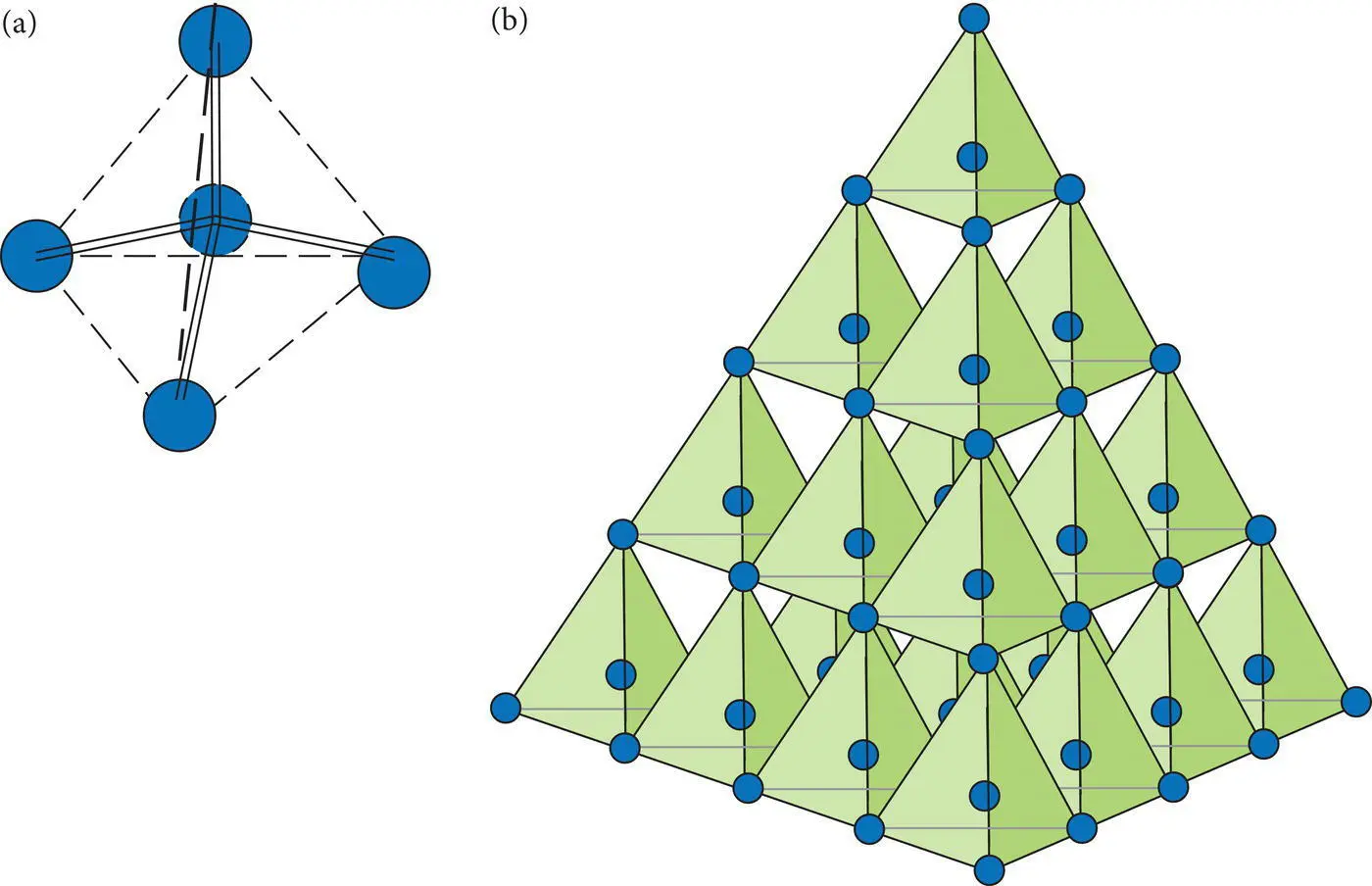

Figure 2.13 (a) Covalent bonding (double lines) in a carbon tetrahedron with the central carbon atom bonded to four carbon atoms that occupy the corners of a tetrahedron (dashed lines). (b) A larger scale diamond structure with multiple carbon tetrahedra.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Earth Materials»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Earth Materials» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Earth Materials» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.