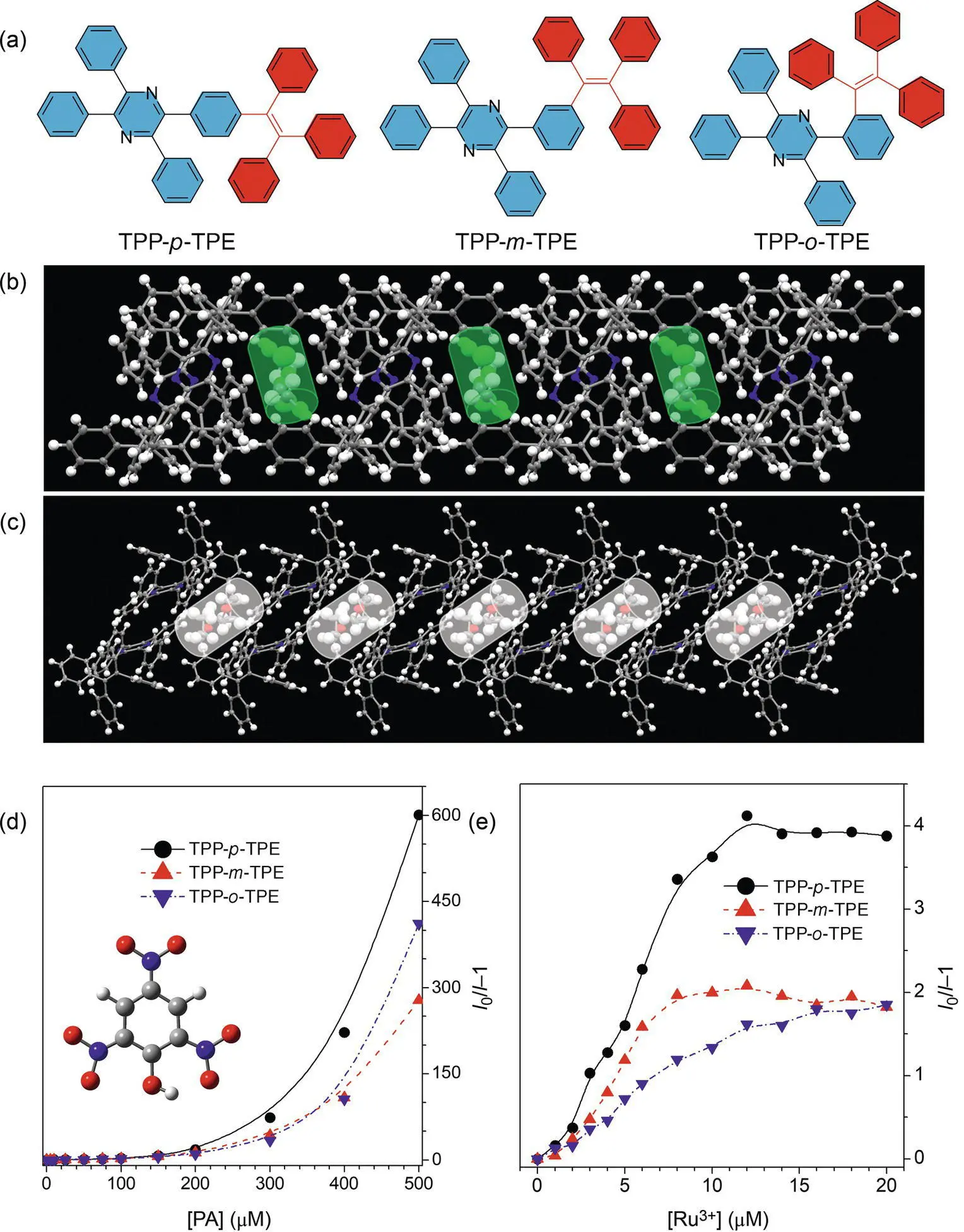

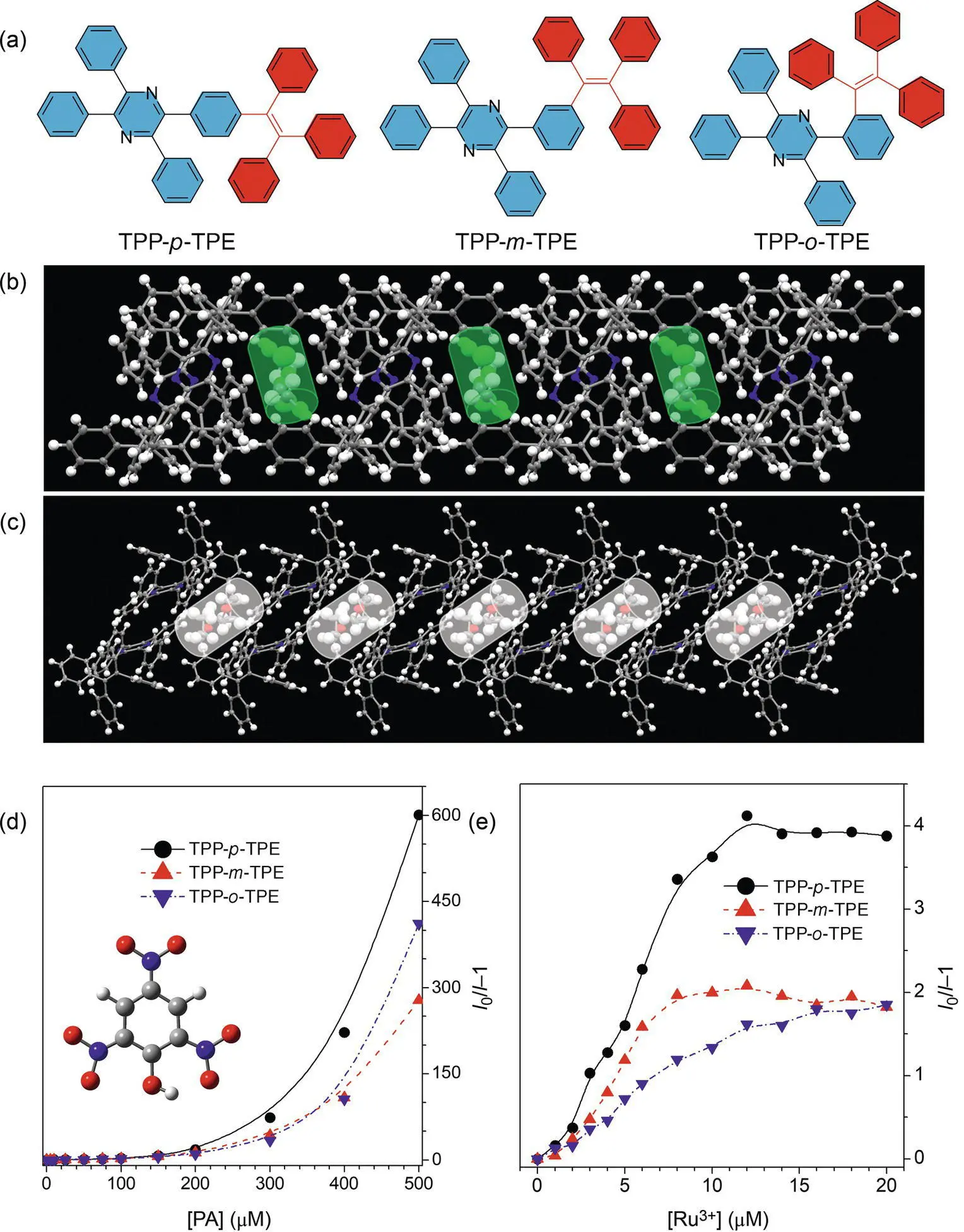

Considering the difference in the influence of molecular conjugation and porosity caused by the isomerization effect, it is desirable to investigate their sensing behavior. 2,4,6‐Trinitrophenol (picric acid, PA) is chosen as the first analyte because it is a well‐known model explosive and the accurate detection of explosive meets current needs in antiterrorist and protection of country safety. The detection is basically carried out with the nanoaggregates in solution because of the strong emissions of AIE isomers in the aggregate state. Upon addition of PA, the isomers show similar quenching behavior as the concentration of PA increases. The lifetime of the three sensors has a negligible change before and after analyte addition, demonstrating that a static quenching model dominates the sensing mechanism. Since the process normally takes place from the ground state of isomers to the excited state of PA, no excited‐state behaviors of sensors such as fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) and photoinduced electron transfer (PET) will occur, while the interaction between the sensor and the analyte plays a crucial role. Overall, the quenching effect of TPP‐ p ‐TPE is somewhat higher than those of the others at high PA concentration. It is due to the stronger Lewis acid–base interactions preferred to take place between PA and AIE isomers with better conjugation. On the other hand, although TPP‐ o ‐TPE possesses the worst molecular conjugation, its quenching effect is a bit larger than TPP‐ m ‐TPE at a PA concentration of 400–500 μM, which is because of its best porosity that increases the binding capacity between TPP‐ o ‐TPE and PA. Therefore, both factors collectively determine the detection of PA by nanoprobes ( Figure 1.2d).

The study is then focused on the sensing of another analyte of Ru 3+by the nanoaggregates because it is important in catalysis but harmful to the environment and toxic to the human beings ( Figure 1.2e) [55]. Different from the above research, the isomers show a partial quenching behavior upon addition of Ru 3+. The quenching keeps linear at a low‐concentration range of Ru 3+and reaches plateaus at high concentrations. Besides, the quenching constant of TPP‐ p ‐TPE, TPP‐ m ‐TPE, and TPP‐ o ‐TPE increases accordingly. The lifetime study indicates that an obvious decrease of lifetime of sensors is observed after addition of Ru 3+. Thus, the quenching mechanism is mainly ascribed to a dynamic (collisional) quenching model, which requires a close contact of the excited molecules and the analyte. The Dexter energy transfer is dominated because a short distance of the donor and the acceptor may help the electron exchange between them. On the other hand, the possible influence of FRET on the sensing is ruled out because all the emissions should be quenched if it exists. It seems that the change of the quenching constant of the sensors is related to the variation in the PL quantum efficiency of isomers. It is more likely that the interaction of the isomers and Ru 3+plays a major role and a much strong interaction will be produced between Ru 3+and isomers with better conjugation.

Figure 1.2 Fluorescent detection of PA and Ru 3+by AIE isomers. (a) Molecular structures of AIE isomers. (b) DCM‐ and (c) THF‐containing organic porous crystals of TPP‐ o ‐TPE. (d) Plots of I 0/ I ‐1 versus PA concentration. Inset: molecular structure of PA. (e) Plots of I 0/ I ‐1 versus Ru 3+concentration. Inset: molecular structure of PA. In (d) and (e), I 0and I are the peak intensity of probes before and after the addition of analytes, respectively, and the excitation wavelengths of TPP‐ p ‐TPE, TPP‐ m ‐TPE, and TPP‐ o ‐TPE are 350, 336, and 332 nm, respectively.

Although the quenching efficiency of TPP‐ m ‐TPE is larger than that of TPP‐ o ‐TPE at low concentrations, it displays the same quenching extent at high concentrations. As the TPP‐ o ‐TPE is an easy‐to‐form pore in the aggregates, the sensor will encapsulate more Ru 3+into the nanoaggregates, which will enhance their interactions. On the other hand, the presence of 3D voids in the probes may help Ru 3+to diffuse and contact more fluorogens to annihilate the emission. Both factors enable the TPP‐ o ‐TPE to possess similar quenching extent with TPP‐ m ‐TPE, while the plateaus of the former will be reached at a higher Ru 3+concentration. However, the isomerization effect has less influence on the selectivity of the sensors.

For examples, by addition of other metal ions like Ag +, Fe 3+, and Cu 2+, etc., no fluorescent response can be observed.

1.3.3 Chiral Cage for Self‐assembly to Achieve White‐light Emission

Organic cage compounds have drawn considerable attention due to their wide functionalities in self‐assembly, gas adsorption, and catalysis, etc [56]. Currently, the organic cages are basically designed based on the classical organic reactions of specific building units. The conjugated units are promising in organic cage design, and the study of optical properties of organic cage is attractive by introduction of these units. However, most of the conjugated units possess ACQ effect. There are few studies on AIE unit‐based organic cages because of lack of AIE prototype structures with good symmetry for design.

As we know, TPP is an AIEgen with four peripheral phenyl rings symmetrically attached to the central pyrazine. Thus, utilization of TPP to develop a luminescent cage is very promising. Tang reported the synthesis of an amphiphilic organic cage with tetrahydroxyl‐substituted TPP (TPP‐4OH) and substituted 2,6‐dichloro‐1,3,5‐triazine ( Figure 1.3a) [57]. TPP‐4OH shows very weak emission in the solution due to the vigorous molecular motion under excitation. However, the TPP cage shows a strong emission at 397 nm with a Φ Fof 34.3% ( Figure 1.3b). Theoretical studies reveal that the rotational energy barrier for the phenyl rings' flipping in the TPP cage is much larger than that in TPP‐OH, which is due to the congested array of each unit in the cage. As the motion of TPP is greatly prohibited in the cage, TPP cage thus exhibits strong emission by suppressing the nonradiative transition. This study also verifies that the restriction of molecular motion is the cause of the AIE effect.

The studies of chirality are closely related to medicinal chemistry and 3D organic electronics. So far, the introduction of a chiral carbon atom into the structure can be regarded as the main source in designing chiral compounds. Interestingly, the TPP cage here also possesses a chirality though no chiral carbon atom is incorporated. Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy indicates that a Cotton effect occurs in the absorption regions of the phenyl rings and TPP units in both the solution and aqueous suspensions ( Figure 1.3c, d). It is due to the clockwise or anticlockwise rotation of the phenyl rings of TPP against the pyrazine ring caused by the steric effect. Such a special molecular conformation enables it to possess mirror asymmetry to show chirality. Theoretically, the TPP cage with the clockwise or anticlockwise propeller is often obtained in a ratio of 1 : 1 after synthesis, and the resulting racemic mixture should quench the chirality. The reason for inducing chirality awaits further investigation. On the other hand, only a stable right‐handed crystal can be obtained in the air, which shows a positive Cotton effect that originates from the crystallization‐induced asymmetric transformation by destroying the mirror symmetry. Moreover, the CD signals of the TPP cage in the aggregates are much larger than those in the solution, indicative of an aggregation‐induced chirality that has rarely been reported.

Читать дальше