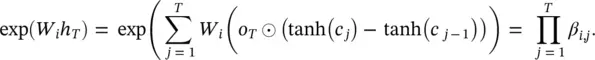

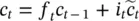

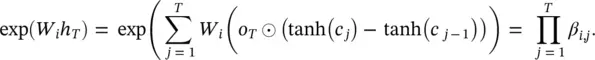

so that

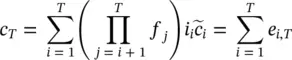

As tanh ( c j) − tanh ( c j − 1) can be viewed as the update resulting from word j , so β i, jcan be interpreted as the multiplicative contribution to p iby word j .

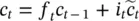

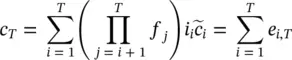

An additive decomposition of the LSTM Cell: We will show below that β i, jcaptures some notion of the importance of a word to the LSTM’s output. However, these terms fail to account for how the information contributed by word j is affected by the LSTM’s forget gates between words j and T . Consequently, it was empirically found [93] that the importance scores from this approach often yield a considerable amount of false positives. A more nuanced approach is obtained by considering the additive decomposition of c Tin Eq. (4.28), where each term e jcan be interpreted as the contribution to the cell state c Tby word j . By iterating the equation  , we obtain that

, we obtain that

(4.28)

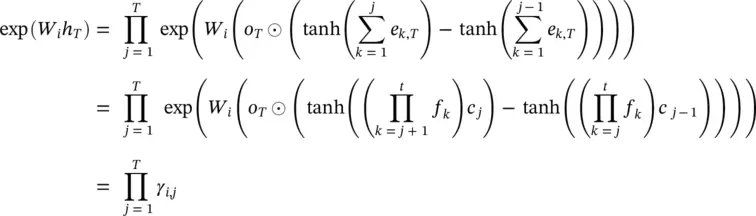

This suggests a natural definition of an alternative score to β i, j, corresponding to augmenting the c jterms with the products of the forget gates to reflect the upstream changes made to c jafter initially processing word j :

(4.29)

We now introduce a technique for using our variable importance scores to extract phrases from a trained LSTM. To do so, we search for phrases that consistently provide a large contribution to the prediction of a particular class relative to other classes. The utility of these patterns is validated by using them as input for a rules‐based classifier. For simplicity, we focus on the binary classification case.

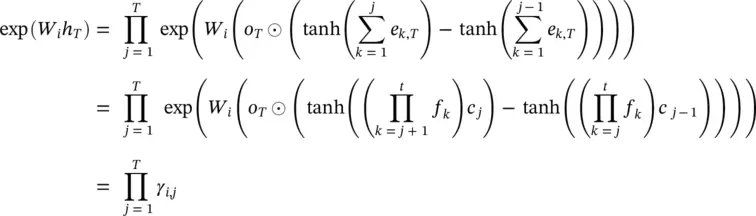

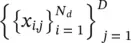

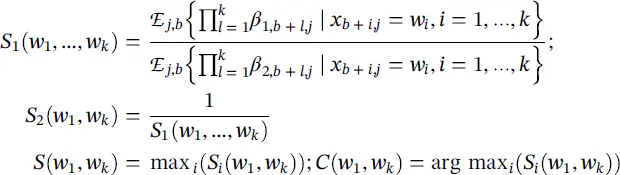

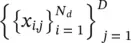

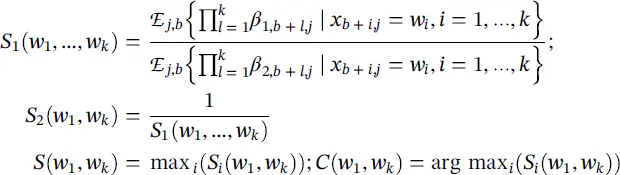

Phrase extraction: A phrase can be reasonably described as predictive if, whenever it occurs, it causes a document to both be labeled as a particular class and not be labeled as any other. As our importance scores introduced above correspond to the contribution of particular words to class predictions, they can be used to score potential patterns by looking at a pattern’s average contribution to the prediction of a given class relative to other classes. In other words, given a collection of D documents  , for a given phrase w 1, …., w kwe can compute scores S 1, S 2for classes 1 and 2, as well as a combined score S and class C as

, for a given phrase w 1, …., w kwe can compute scores S 1, S 2for classes 1 and 2, as well as a combined score S and class C as

(4.30)

where β i,j,kdenotes β i, japplied to document k and  stands for average.

stands for average.

The numerator of S 1denotes the average contribution of the phrase to the prediction of class 1 across all occurrences of the phrase. The denominator denotes the same statistic, but for class 2. Thus, if S 1is high, then w 1, …, w kis a strong signal for class 1, and likewise for S 2. It was proposed [93] to use S as a score function in order to search for high‐scoring representative phrases that provide insight into the trained LSTM, and C to denote the class corresponding to a phrase.

In practice, the number of phrases is too large to feasibly compute the score for all of them. Thus, we approximate a brute force search through a two‐step procedure. First, we construct a list of candidate phrases by searching for strings of consecutive words j with importance scores β i, j> c for any i and some threshold c . Then, we score and rank the set of candidate phrases, which is much smaller than the set of all phrases.

Rules‐based classifier: The extracted patterns from Section 4.1can be used to construct a simple rules‐based classifier that approximates the output of the original LSTM. Given a document and a list of patterns sorted by descending score given by S , the classifier sequentially searches for each pattern within the document using simple string matching. Once it finds a pattern, the classifier returns the associated class given by C , ignoring the lower‐ranked patterns. The resulting classifier is interpretable, and despite its simplicity, retains much of the accuracy of the LSTM used to build it.

4.4 Accuracy and Interpretability

This section focuses on the accuracy and interpretability trade‐off in fuzzy model‐based solutions. A fuzzy model based on an experience‐oriented learning algorithm is presented that is designed to balance the trade‐off between both of the above aspects. It combines support vector regression (SVR) to generate the initial fuzzy model and the available experience on the training data and standard fuzzy model solution.

Fuzzy systems have been used for modeling or control in a number of applications. They are able to incorporate human knowledge, so that the information mostly provided for many real‐world systems could be discovered or described by fuzzy statements. Fuzzy modeling (FM) considers model structures in the form of fuzzy rule‐based systems and constructs them by means of different parametric system identification techniques. In recent years, the interest in data‐driven approaches to FM has increased. On the basis of a limited training data set, fuzzy systems can be effectively modeled by means of some learning mechanisms, and the fuzzy model after learning tries to infer the true information. In order to assess the quality of the obtained fuzzy models, there are two contradictory requirements: (i) interpretability , the capability to express the behavior of the real system in a way that humans can understand, and (ii) accuracy , the capability to faithfully represent the real system. In general, the search for the desired trade‐off is usually performed from two different perspectives, mainly using certain mechanisms to improve the interpretability of initially accurate fuzzy models, or to improve the accuracy of good interpretable fuzzy models. In general, improving interpretability means reducing the accuracy of initially accurate fuzzy models.

It is well known that support vector machine (SVM) has been shown to have the ability of generalizing well to unseen data, and giving a good balance between approximation and generalization. Thus, some researchers have been inspired to combine SVM with FM in order to take advantage of both of approaches: human interpretability and good performance. Therefore, support vector learning for FM has evolved into an active area of research. Before we discuss this hybrid algorithm‚ we discuss separately the basics of the FM and SVR approach.

Читать дальше

, we obtain that

, we obtain that

, for a given phrase w 1, …., w kwe can compute scores S 1, S 2for classes 1 and 2, as well as a combined score S and class C as

, for a given phrase w 1, …., w kwe can compute scores S 1, S 2for classes 1 and 2, as well as a combined score S and class C as

stands for average.

stands for average.