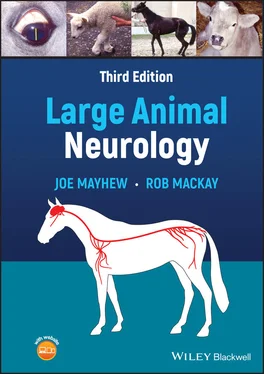

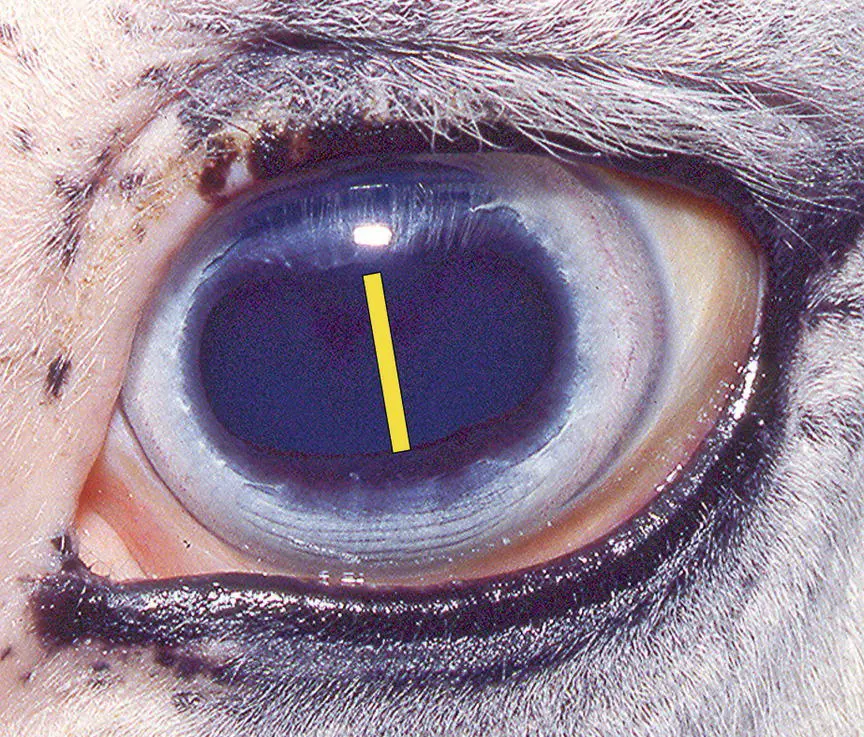

A mydriatic pupil with normal vision is seen with parasympathetic oculomotor nerve involvement in large animals, although this is not commonly seen in isolation. The accompanying classical lateral and ventral (down and out) strabismus with ptosis due to somatic motor CN III lesions is also not often seen in large animals but occurs with basilar and sphenoidal sinus diseases. When mydriasis with an inability of the iris to constrict is found with no other neurologic abnormalities, previous atropine therapy must be considered ( Figure 10.2). Many asymmetric inflammatory, traumatic, and vascular brain diseases can result in midbrain oculomotor involvement and anisocoria. Space‐occupying and other forebrain lesions associated with brain swelling can result in subsequent ventral pressure on the midbrain and hence onto the oculomotor nerves ( Figure 4.8). When such lesions are asymmetric, they then cause anisocoria with poorly responsive pupils that can be accompanied by degrees of blindness, depending on whether the optic nerves and light pathways are also affected.

Figure 10.2 With this degree of bilateral pupillary dilation found in normal ambient room light (yellow bar), the possibility that it is due to a frightened or painful patient must be considered. Especially if this is asymmetric, the effects of previous application of a mydriatic have also to be considered. This patient had received one application of atropine in this left eye 36 h previously and even in sunlight left mydriasis was maintained (see also Figure 13.2).

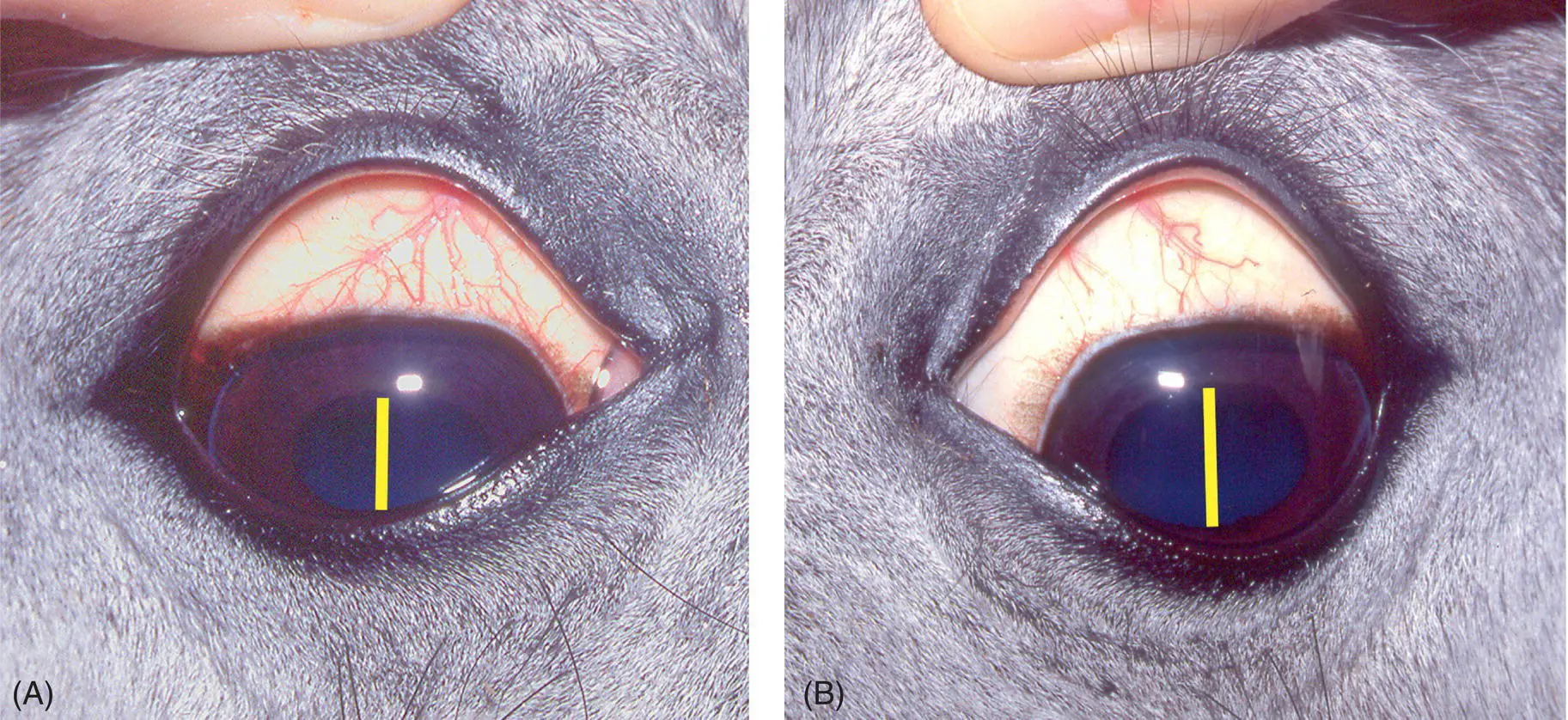

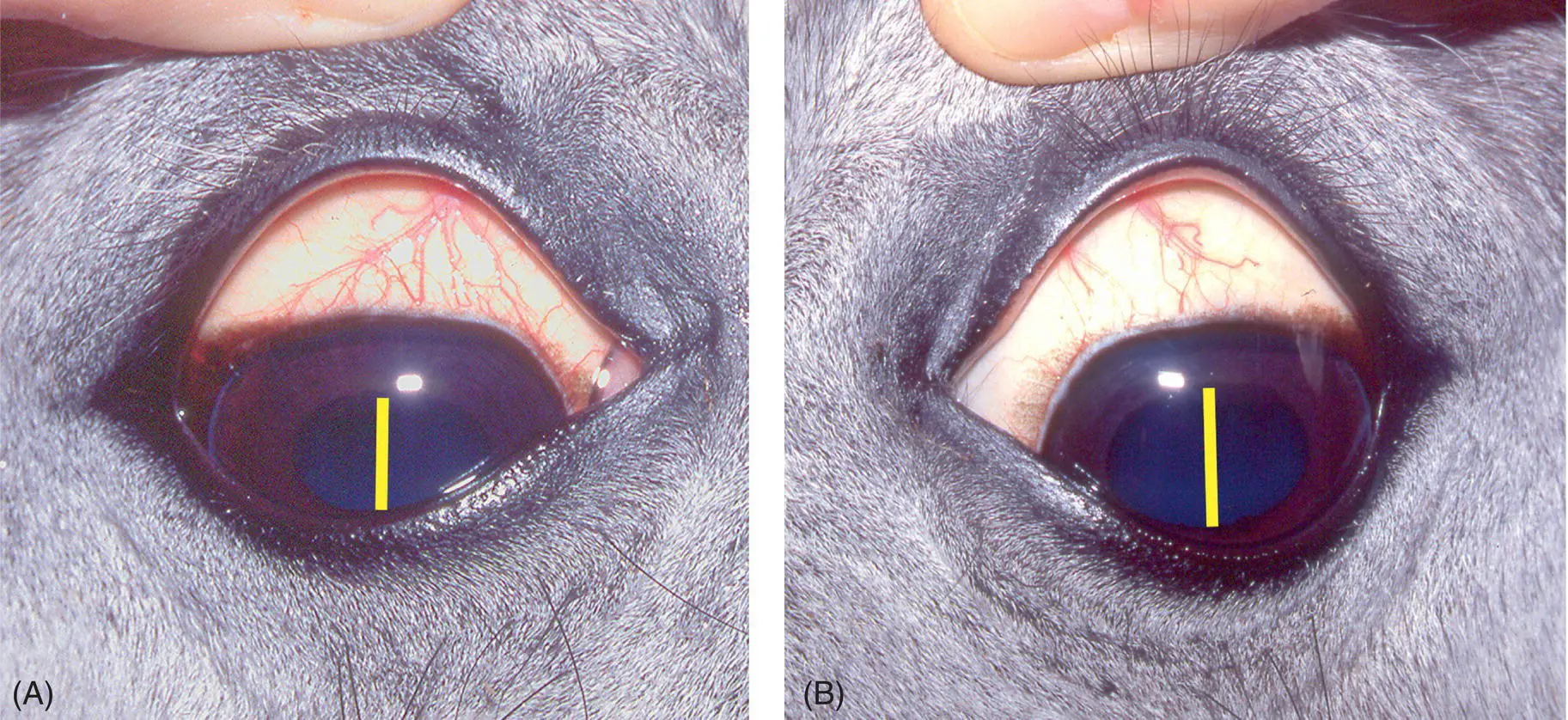

In accordance with the global trend for the use of nonpossessive eponyms, 12we shall use the descriptor Horner syndrome —as opposed to Horner’s syndrome—to describe the signs associated with sympathetic denervation (decentralization) of the head of animals. The degree of miosis seen in sympathetic denervation of the eye (Horner syndrome) is very variable and not dramatic in large animals, and neither is enophthalmos and protruding nictitating membrane ( Figures 10.3and 10.4). 313–19Horner syndrome in horses consists of miosis and ptosis of the upper eyelid as in other species, and these signs alone can be seen with retrobulbar lesions involving postganglionic sympathetic fibers. Ptosis is due to paralysis of the sympathetically innervated Műller superior tarsal smooth muscle. In addition, hyperemic mucous membranes of the head ( Figure 10.3), hyperthermia of the face, 20,21and in horses sweating of the face and cranial neck are evident with more proximal sympathetic lesions ( Figures 2.10, 10.5, and 10.6). These latter findings are caused by the interruption of sympathetic fibers to the skin (blood vessels and sweat glands) of the head and neck. 19Although sweat glands in horses, as in other mammals, may not be directly innervated, 22sympathetic denervation of the head causes cutaneous vasodilation so that more circulating adrenalin is brought to the sweat glands, and this neurohormone has powerful sudomotor effects in horses. 22,23If the sympathetic fibers are affected at the level of, or distal to, the cranial cervical ganglion in the wall of the guttural pouch, sweating over the head projects caudal only to the level of the atlas. Preganglionic lesions proximal to this level, as in the neck, result in sweating further down the neck to the level of the axis to C3. 18, 21Cranial thoracic lesions can affect the sympathetic fibers not only in the cervical sympathetic trunk, but also those innervating the skin of the remainder of the neck traveling with the vertebral nerve and segmental dorsal spinal nerve roots ( Figure 2.10). Then, there is sweating over the whole neck and head ( Figures 2.10and 10.6). A first‐order sympathetic neuronal lesion in the descending, tectotegmento‐spinal tract in the brainstem or cervical spinal cord results in sweating on the whole side of the trunk, neck, and head as well as the eye signs of Horner syndrome. 18Of some diagnostic interest is that at least for horses with acute sympathetic lesions and distributions of sweating, the administration of α‐2 agonist sedative drugs will result in expected sweating over normal skin of the body but often reverses the vasodilation and sweating over the sympathetically denervated skin such that it becomes dry.

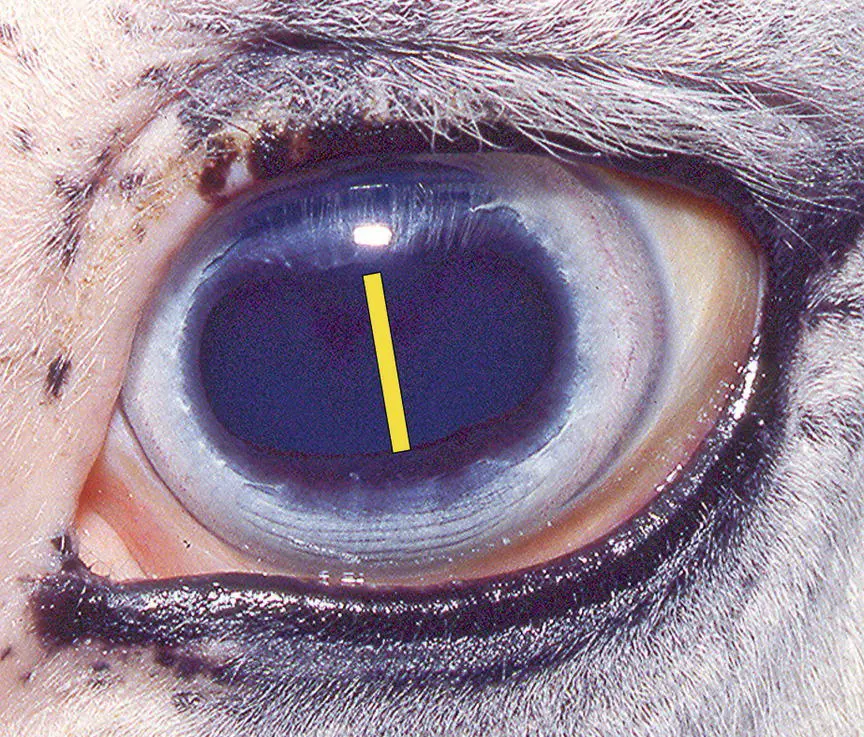

Figure 10.3 Left Horner syndrome present in this horse (A) is evident as moderate ptosis, lowering of the upper eyelashes and miosis (C) compared with the unaffected side (B). Note that there is still an angle present at the medial margin of the upper lid that is usually much less apparent with the ptosis seen with facial CN VII paralysis.

Figure 10.4 In this case of acute, temporary, experimental Horner syndrome induced by local anesthetic blockade of the cervical sympathetic trunk, a slightly constricted pupil is evident (A) compared with the normal eye (B). In horses, loss of sympathetic tone to superficial blood vessels induces vasodilation and this can be seen on any affected mucous membrane such as the pharynx and larynx, and the bulbar conjunctiva in this case (A). Ptosis is not evident as the eyelids are being held open.

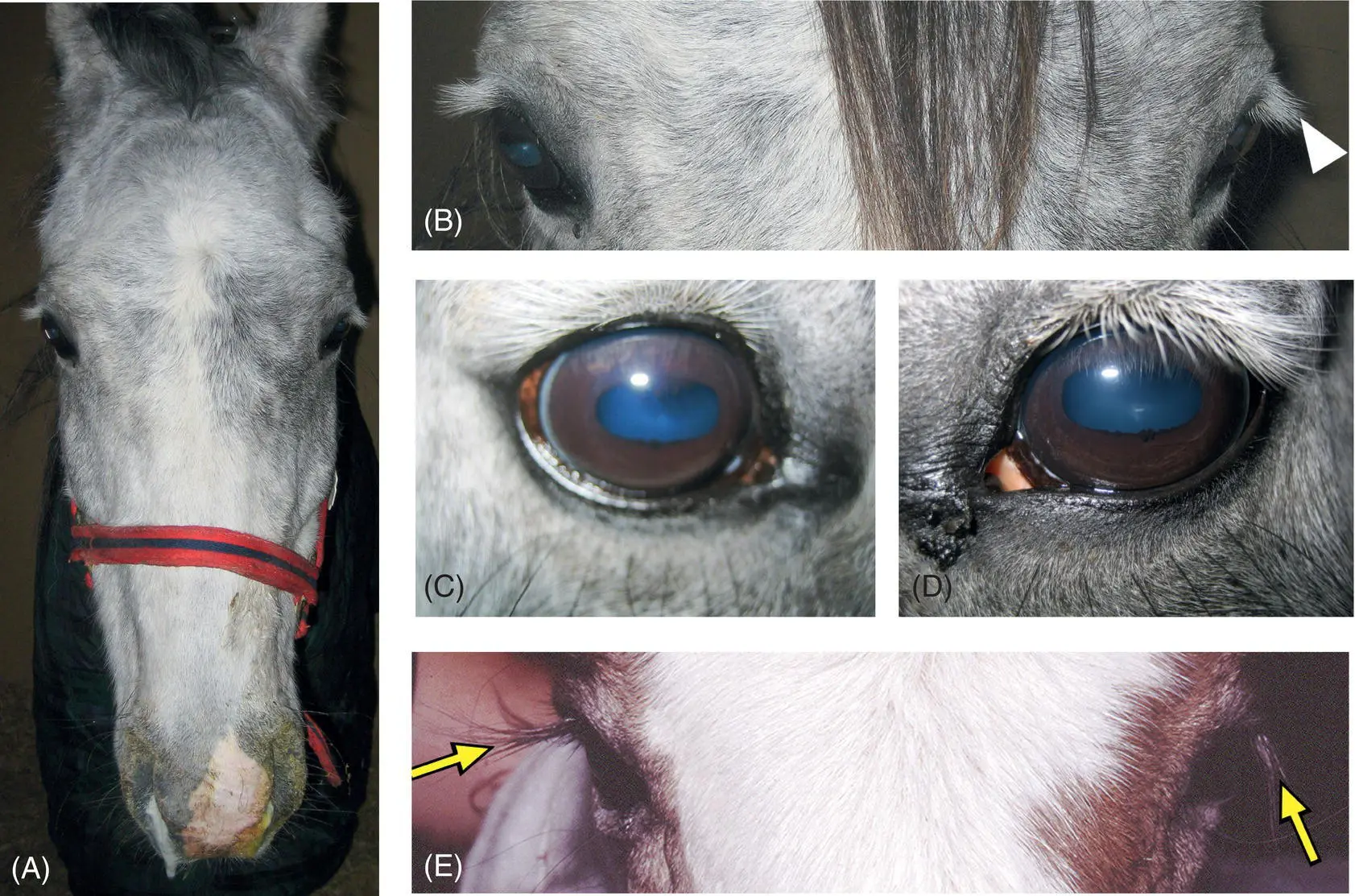

Figure 10.5 This horse is suffering from guttural pouch (GP) mycosis with evidence of pharyngeal dysphagia (A) along with left‐sided Horner syndrome shown as mild ptosis of the upper lid (arrowhead in (B)) and accompanied by facial sweating (A) down to the level of C2 on the neck and even evident under the eye on the left (D) compared with the right (C) side. This is to be distinguished from facial nerve paralysis in that there is no weakness to closing the eyelids when there is loss of sympathetic tone to the eyelids. The classical signs of Horner syndrome are seen in the horse’s left eye (D) when compared to the normal right eye (C). Mild miosis and enophthalmos with slight protrusion of the nictitating membrane are evident along with the ptosis. A prominent component of the ptosis in this syndrome compared with facial paralysis is the lower angle of the upper eyelashes (D) rather than marked lowering of the upper lid, especially the medial aspect, that more typifies facial paralysis. A useful test to help confirm the presence of Horner syndrome is to instill 0.5 mL of 0.5% phenylephrine into the conjunctival sac and observe for correction of the lowered eyelashes. This is shown in (E) where a case of bilateral Horner syndrome has been treated on the right side to correct the ptosis (yellow arrows).

Figure 10.6 This horse was injected with local anesthetic solution in the caudal cervical region. It demonstrated Horner syndrome and sweating over the face and cranial cervical region, especially at the base of the ear. Additionally, there was prominent sweating on the neck over the C 3to C 6dermatomes. The local anesthetic solution almost certainly spread caudally along the cervical vagosympathetic trunk to the region of the cervicothoracic ganglion. This would then produce blockade of the sympathetic supply to the skin of the neck at the levels of C3 to C6 in addition to blocking the cervical sympathetic trunk that causes sweating over C1 and C2 only (See also Figure 2.10).

Читать дальше