People who had lived and worked on farms all their lives came on deck and gripped the handrail. It was lush land, they thought to themselves, green and fertile. After what they had been through, this at least they needed to believe.

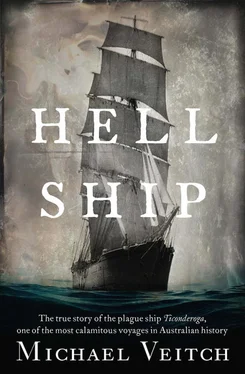

On a clear and bright early morning, after a journey of nearly 13,000 miles, the Ticonderoga arrived outside the entrance to Port Phillip Bay. Negotiating the formidable Heads was not a task to be taken lightly, particularly for those unaccustomed to its tricks and peculiarities. Beyond its entrance stretched a vast, almost entirely landlocked, inland bay measuring nearly 800 square miles. But first, the infamously treacherous passage between its two guarding promontories, known appropriately to sailors everywhere as ‘the Rip’, needed to be navigated. Although 2 miles of water separated the Heads—Point Lonsdale on the west and Point Nepean on the east—the intervening Rip was riven by a chaotic pattern of reefs reaching out from both points, reducing the true navigable distance to a gap little more than half a mile wide. A mistake made here would not be forgiven. So treacherous was the Rip, in fact, that even the government pilot vessels were reluctant to traverse it to bring vessels in. That risk, in most cases, would have to be undertaken by the captains themselves. According to his Notes to Mariners, Boyle was required to make his own way through the Rip to a small outcrop on the western arm near the fishing village of Queenscliff named Shortland’s Bluff. Once here, he was to signal for a pilot to guide him through the fairways to the shipping channel and eventually up to the port of Melbourne, Port Phillip itself. With the sandy floor of the bay at an average depth of only 26 feet, this was not a course Boyle wanted to tackle unaided.

He would have appreciated that same help with tackling the Rip itself, where unpredictable waves, eddies and currents abounded. Then there were the tidal streams that ran through it at up to 6 knots, and vastly differentiating depths—between 5 and 100 metres—making for surges that had already trapped scores of vessels, such as the 500-ton Isabella Watson. Eight months previously, this passenger barque had come to grief, taking nine lives with her, executing exactly the manoeuvre that Boyle, in a much larger ship, was now about to attempt. He could clearly see the Isabella Watson ’s broken carcass washed up on a tiny cove just inside Point Nepean, as if placed there as a warning of the dangers that confronted him.

Boyle had studied his Notice to Mariners for the approaches to Port Phillip. Likewise he recalled the warnings to take particular care with the Rip. Slack water between the surge of the tides, he had been advised, would be the safest time to make his approach, but even then a sudden squall or current from below could drag a ship onto a reef or into the infamous natural feature of Corsair Rock, which lay guarding the Rip’s entrance like a sentinel.

Until deemed safe, it was customary for ships to pause outside the Rip, sailing back and forth under half-sail several miles out into Bass Strait, awaiting the most opportune moment to enter, then picking up the pilot to Melbourne. Captain Boyle, however, did not have time on his side. With his passengers dying like flies and 300 suffering various degrees of illness, his priority had to be delivering them to better care, and quickly.

A mate then announced that one of the sailors had in fact sailed to Melbourne several times previously—albeit not recently. Conditions were not ideal, but the water looked calm, a breeze was blowing in his favour and so Boyle decided to make the attempt. Even approaching the entrance from the ocean side was dangerous, as jutting nearly a kilometre into Bass Strait was the Rip Bank, another obstacle that needed to be avoided. A brief conference took place on the upper deck, with charts and notes consulted once again. Standing by the captain and behind the helmsman stood the unnamed seaman who, several years before, had likewise attempted the passage, the weight on his shoulders now feeling much heavier than he would have liked. Boyle looked up and ordered more sail. When all was ready, he then gave the command to bring the Ticonderoga about, and with men placed fore and aft giving soundings, in the great ship went.

Even in calm weather such as this, Boyle felt the surge of eddies tugging at the ship as it negotiated the bottleneck . Around him was a true patchwork of ocean temperaments: white water here, a smooth glassy upsurge from deep below there. Shadows flitted by as she glided over alternating patches of dark reef and pale sand. Boyle quickly appreciated the reputation of this torrid piece of water among sailors the world over. Running before the wind, the shore now began to move past. A line of little white stone cottages became visible, the first signs of habitation of this new land.

Then the soundings indicated more water beneath them and the sea settled to its dark bluey grey. They were past the Heads and through the Rip of Port Phillip Bay. Rounds of ‘Well done! Well done!’ made their way along the upper deck from the captain and first mate. Boyle trimmed the yards as the Ticonderoga ’s bow edged towards the low hump of Shortland’s Bluff. Then came the order that every soul on board had, for 90 agonising days, longed to hear, ‘Come to anchor!’

‘Ay, Cap’n,’ came the response, and the magnificent clanking of the great anchor chain, finally released, reverberated throughout the ship. Finding a sound bottom, the Ticonderoga swayed for a moment, then rode at her anchor, still.

* * * *

Henry Draper had been part of the Port Phillip pilot service for less than a year, but his time thus far had been anything but uneventful. As first mate of the barque Nelson, he had arrived in Melbourne from England in 1851, disembarked a load of privately paying passengers, and was preparing to load up for the return journey with a cargo of 2600 bales of wool and 9000 ounces of gold, which arrived under escort by steamer. After loading, his skipper, a Captain Wright, unwisely chose this moment to go ashore for a last carouse before their departure the next morning. Riding at anchor at Hobson’s Bay, Draper was awakened in his cabin during the night by sounds of scuffling on the deck. Emerging, he soon found himself surrounded by an armed gang who were preparing to liberate the ship’s store of gold. In the drama, a pistol was discharged at one of the mates, the ball missing him but grazing Draper’s hip. The bandits then locked the entire crew up and made off with the gold.

The ship’s cook, who had escaped attention by hiding under his bunk, released Draper, who then swiftly raised the alarm upon rowing ashore. The bandits were soon rounded up. Draper would have liked nothing better than to have simply left as planned the next morning, but as a witness to a robbery, he was now compelled to cool his heels for several weeks awaiting a trial. He was in the meantime feted as a minor hero, awarded a total of £170 for his troubles and visited by Port Phillip’s Chief Harbour Master, Charles Ferguson, who promptly offered him a job. ‘I received the request with astonishment,’ Draper later wrote, ‘as I considered my position far above that of a pilot’s.’ His pride quickly recovered, however, when told that his salary would be in the range of £100 per year. [1] H. Draper, ‘The Narrative of Captain H.J.M. Draper, One Time Port Phillip Sea Pilot’, reproduced in The Log: Quarterly Journal of the Nautical Association of Australia Inc , February 2002, vol. 35, no. 1, issue 47, p. 6

A year into the job, Draper was being kept busy at the pilot station at Shortland’s Bluff. The discovery of gold had seen a huge increase in shipping entering the bay, but his small group of pilots still had just two oared whale boats and a cutter at their disposal to guide as many as ten vessels a day both through the Rip and into the shipping lanes that cut their way through the shallow sandy banks up to the busy port of Melbourne. Early November was a particularly active time, and the records show that on the day the Ticonderoga came in, another nine ships also entered, many needing assistance. Few days of his career, however, would be as dramatic as this bright November morning when he answered the request of a large, dark emigrant ship lying at anchor off Shortland’s Bluff. She was, he could see, an unusually fine clipper, but as he approached her in his pilot’s cutter, he sensed all was not well. He could see people on deck, but they were few in number and appeared unsettled. Then, as he came within earshot, a series of desperate shouts could be heard, ‘Don’t come on board, pilot,’ he was told. ‘We are dying of fever!’

Читать дальше