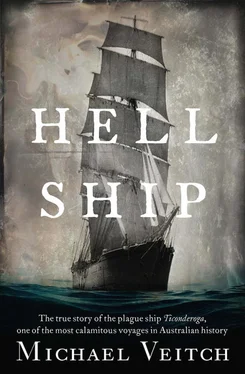

Dr Sanger’s urgent words, delivered to Captain Boyle as he too was preparing to enjoy the colour of King Neptune’s antics, were met with a dread. ‘Typhus?’ he could only repeat. ‘Not scarlatina?’ But Dr Sanger was certain. The scourge of typhus had come to the Ticonderoga.

A day or so later, his grim prognosis was borne out when 28-year-old Jane Gardiner joined her daughter, Eliza, the Ticonderoga ’s second victim, who had perished three weeks earlier at just four years of age. She left behind her husband, Alexander, and their sole remaining child, Robert, five. One of the Ticonderoga ’s English families, the Gardiners had left their home in Northumberland full of hope for a better life. Now, barely a month later, only a shattered widower and his son remained.

There had already been a regular procession of death on board the Ticonderoga. Besides Anna Maria Hando, the infant son of Alexander and Ellen Mercer, Andrew, had been buried at sea, as had one-year-old Mary Ann Ross, Christina Jenkins, also one year of age, and tiny Margaret McJames. In at least two cases, the children’s grief-stricken mothers had thrown themselves overboard as well. As ghastly a toll as this appears to a modern reader, it was still not regarded as very much out of the ordinary in this age of prevalent disease and short life expectancies.

The three other double-decked ships hired by the Board in 1852 to make the run to Australia had also experienced a high loss of life. In the case of the large 1495-ton Borneuf, which was in fact still on its way to Geelong as the Ticonderoga set sail, 88 of the 754 passengers had not survived the voyage. All but four of these were children—mainly Scots—and all under the age of seven, with the average age being much younger. Most of these deaths were attributed to the typical wasting diseases of the poorer classes of the day: marasmus, scarlatina, measles, diarrhoea and chicken pox. Despite this, the Borneuf ’s journey was regarded as a success.

The death of an adult, however, was another matter, and the passing of Jane Gardiner—an ostensibly healthy woman in her twenties—represented a grim turning point in the Ticonderoga ’s voyage. Drs Sanger and Veitch had watched, helpless, as over a few days the terrible symptoms had worked their damage on the young mother: first the rash that spread from her chest then across her entire body, sparing only the palms of her hands; the temperature that raged through her constitution at up to 105ºF; the nausea, exhaustion and vomiting; the terrible aches in limbs and joints. Then, almost unbearable for her husband and child to watch, the delirium. As the fever set in, the woman’s mind became unhinged in a verbal rampage that terrified those around her in the lower deck’s claustrophobic quarters, then in the ship’s hospital. After this, she fell into a coma. Attempts to both cool her down or administer any kind of medicine were fruitless. The awful smell then led the Ticonderoga ’s doctors to realise exactly what they were dealing with. It could only be typhus, and they were powerless to stop it.

* * * *

For centuries typhus had been one of the great scourges of Europe. Entire armies had been laid waste by the disease. During the wars against the Moors in 1489, it is estimated to have wiped out 17,000 Spanish soldiers during the siege of Granada. In Napoleonic times, it accounted for more French troops than did the Russians during the retreat from Moscow in 1812. In the 1830s, 100,000 Irish died in a series of severe outbreaks and during the Crimean War of the 1850s, war wounds accounted for no more than one in six soldiers’ deaths, the rest being attributed to a variety of diseases, principally typhus.

Even as late as World War I, 3 million deaths were attributed to typhus, and despite the advances of medicine at the dawn of the twentieth century, no one had any idea how it was transmitted. It was, however, observed to act upon large amounts of people living in close, often unsanitary conditions, and hence became known by many descriptive names, including prison fever and camp fever. [1]

It could tear through the populations of army barracks, slums, prisons, hospitals and particularly overcrowded ships such as the Ticonderoga.

The closest anyone could come to explaining the spread of typhus was via the generally accepted ‘miasmatic theory’, by which greatly feared diseases such as cholera, the Black Death and even chlamydia were spread not by infection and contact with germs, but rather by the foul air that seemed to accompany the rapidly expanding cities of the Industrial Revolution, and that appeared to emanate in rotting organic matter. Until the advent of powerful microscopes in the late nineteenth century, the contagion vs. miasma theories competed with one another for years, with even such luminaries as Florence Nightingale believing fervently that diseases she herself witnessed wreaking death and destruction on troops in the Crimea had nothing to do with proximity to others carrying the infection, but instead were carried on the breeze. It was an enduring theory, and it accounted for the notion that fresh, clean air was the key to health in crowded situations like hospitals and ships. In such a light, the Ticonderoga ’s canvas air vents were seen as a most forward-thinking innovation. Towards the 1880s, the miasma theory would gradually be overtaken by weight of evidence of germs and bacteria, but the exact causes of some diseases, including typhus, remained a mystery.

Discovering the causes of infectious diseases had been a lifelong quest for Brazilian physician Henrique da Rocha Lima and his friend, Czech pathologist Stanislaus von Prowazek, with both men taking a particular interest in typhus. At great risk to themselves, they followed outbreaks and epidemics right across Europe, travelling to Serbia in 1913 to study one outbreak, and observing another in Constantinople the following year. In the winter of 1915, as war raged across Europe, they worked to contain a sudden and devastating outbreak among Russian prisoners of war in a camp near Berlin. Here, both men became infected, and von Prowazek quickly died. Da Rocha Lima recovered, however, and became more determined than ever to track down the cause.

In 1916, after a period of intense research, he announced the discovery of an entirely new group of bacteria that, once introduced into a person’s bloodstream, induced the familiar symptoms of high temperature, aches, rashes, delirium, sensitivity to light, often coma and, above all, the terrible stench—all the indications of typhus. In honour of his late colleague and another prominent victim of the disease, an American researcher named Ricketts, da Rocha Lima named his new strain of bacteria Rickettsia Prowazekii, and further announced to the world that the means by which it had, for thousands of years, been introduced into the human system was via one of mankind’s oldest companions, Pediculus humanus humanus , the common body louse. The discovery revolutionised the treatment of typhus. Lice were hunted down and destroyed with purpose and vigour like never before and by World War II, when DDT and later a vaccine had been developed, the incidence had been so reduced that the vaccine’s production was actually halted.

For the passengers and crew of the Ticonderoga , however, such developments were far in the distant future and in 1852, doctors Sanger and Veitch lacked the benefit of any such knowledge. Nor could they have had any idea as to the pathology of the disease: how it will eventually kill the louse itself; how the bacteria contained within its faecal matter will keep living on the surface of human skin for several days; how the unbearable itching of the louse’s bite will cause the patient to scratch, forcing the bacteria directly into the bloodstream; how the incubation period can last up to two weeks; how one single louse can lay up to 200 eggs; and that the ideal environment for the creatures to propagate was in humidity above 40 per cent and in temperatures between 29 and 32ºC—precisely the conditions the Ticonderoga had been experiencing as she sailed slowly south over the warm waters of the equator.

Читать дальше