It is unknown in exactly what section of the Portsea Island Union the young Dr Veitch worked, but it was here that he would face his first test as a physician in an outbreak of one of the most brutal and least understood diseases of the time. In July 1849, a series of inmates began to exhibit certain symptoms that sent a deep chill through the doctors of the Portsea Island Union workhouse. One after another, both men and women began to experience nausea, then vomiting, quickly followed by terrible diarrhoea and drastic fluid loss. Every sign pointed to the dreaded cholera morbus , the unstoppable disease that fifteen years previously had swept Britain in a pandemic lasting two years and killing more than 50,000 people.

First noted among the troops in Bengal in the early nineteenth century, cholera spread across India, Asia and Europe before arriving in the north of England by boat. It spread quickly across the British Isles—believed, like many other ailments, to be spread by airborne miasma, due to its terrible associated stench. It was not until the discovery of germs in 1864 that its true nature as a water-borne disease was understood.

By the time of the next outbreak in 1849, some improvements in sanitation had occurred, even though another 50,000 would again perish across England and Wales, exacerbated by the arrival of already weak and under-nourished Irish fleeing the effects of the recent potato famine.

Portsmouth at the time was lamented as having some of the most dire poverty and poorest sanitation conditions in the country, due in part to it being a walled and fortified island town with a compressed network of dank and narrow streets compounding any illness that took hold. Set a little way back from the fine high street along which the wealthy wives of senior naval officers would regularly promenade, Portsmouth’s poorer houses were badly built, allowing damp to permeate into badly clothed human bodies through broken windows and dilapidated cellars. Rates of poverty and malnutrition were high, with mortality rates—particularly for children under five—being well above the national average. Out in the harbour, rotting convict hulks housed their own cargo of human misery.

In just two months, the epidemic tore through the Portsmouth area, taking 676 victims. The confined spaces of the Portsea Island Union were not immune, but the resident doctors did their utmost to limit the impact on their inmates. In the crisis, James Veitch proved himself a resourceful and capable physician, his tireless efforts in reinforcing cleanliness and seeing—to the best of his abilities—to the comfort of his patients at great personal risk coming to the notice of the medical authorities. Letters praising the young Veitch were written, the most effusive being that of the district medical officer, countersigned by six other prominent members of the medical establishment of the day:

We the Committee of Public Health in the Portsea Island Union, do hereby certify, that Mr James William Henry Veitch, Surgeon, was engaged by us as an additional medical assistant in consequence of the prevalence of Cholera in the union in the months of July, August and September last, and that during the whole period of his engagement he shewed very considerable skill and was most attentive in the performance of his duties; and we accord to him our best thanks. Dated the first day of October, 1849, JT Pratt, Chairman [11] Private letter in collection of Veitch family history of Pat Hocking

The commendation, as well as his prestigious name, brought Veitch to the attention of the Board. In particular, his proven ability in the face of an epidemic led them to conclude that he was the perfect candidate to assist one of their most respected surgeons, Joseph Sanger. In the middle of 1852, an offer was made to the young Veitch and, to the delight of the Board, it was accepted immediately. Should this first appointment go well, he was told, there would be many more such appointments, as competent and reliable physicians were highly sought after. For this initial journey, the fee would be limited to not more than £80, but—the Board was at pains to point out—this could escalate quickly.

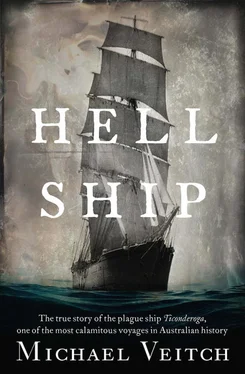

Veitch was told he would be travelling on board the Ticonderoga , a fast American double-decker clipper, one of four such vessels hired by the Board to sail to Port Phillip this year, each carrying close to 800 passengers to cope with the acute demand for travel to the Australian colonies due to the discovery of gold.

The regulations regarding the amount of children, it was explained, had recently been relaxed, so there would be a large number of youngsters on board and the risk of disease would be high. The ship, however, had been meticulously fitted out with many new innovations to ensure the highest standards of cleanliness and hygiene, and her master, Captain Boyle, was as capable and as conscientious a master mariner as could be found anywhere. Only when pressed, James Veitch said that he indeed felt himself qualified for the role, and the men of the Colonial Land and Emigration Commission wholeheartedly agreed.

Eight hundred people did, however, seem rather a lot for one ship.

‘Captain, I believe we have a case of typhus on board,’ said Dr Sanger to Captain Boyle, bringing him out of earshot of a group of passengers standing nearby on the upper deck. Boyle’s blood ran cold at the news, but he maintained his demeanour, not wishing the passengers to observe his unease. After all, everyone seemed to be enjoying the party.

In the first week of September, at latitude 3 degrees 19’ north; longitude 20 degrees 24’ west, the ship’s company of the Ticonderoga was in a festive mood, preparing in the next day or so to cross ‘the line’ of the equator—a significant moment on any sea voyage. Despite the heat of the tropics and at times enervating humidity to which no one was accustomed, the mood of the passengers was high. The day before, the first of the monthly scheduled changes of clothes had taken place, and the crew, assisted by many of the single men, had hauled up some of the hundreds of colourful boxes and trunks to allow people to reacquaint themselves with their possessions, transforming the Ticonderoga ’s normally functional upper deck into something resembling a lively and colourful market. For many, handling again something that was personal and familiar seemed like a brief but blessed return to normality.

Meanwhile, some of the sailors were busy preparing their costumes for the time-honoured ceremony of the line crossing. In reality, these amounted to little more than bits of whatever scraps and flotsam that could be found around the ship, but the stage was soon set to welcome the King of the Deep, Neptune, his ‘wife’, Amphitrite, and several of their cohort, who would be ushered aboard and, with great flourish, interrogate the captain. ‘Where are you from?’ the sea god would ask rhetorically. ‘How long have you been out? For where are you bound?’ The captain would also be asked how many ‘children’ he had on board in need of a ‘baptising’ to mark the occasion of their first crossing. The assembled passengers, enjoying this moment of levity, ooh-ed and aah-ed at all the appropriate moments, as if watching a music hall show.

Then there was an announcement from the top of the wheelhouse through a loud hailer that those who had never before crossed the line would now be sought out and should prepare themselves for the ‘ceremony’. In the case of the Ticonderoga , this was almost everyone, so the practicalities of performing the often revolting ‘initiation’ of being shaved, covered in tar or other filth or, for the ladies, simply soaked to the skin were quietly abandoned in favour of a good deal of noise, cheering and parading around the upper deck as the equatorial sun blazed high overhead. For good theatrical measure, a few first-timers were rounded up and locked into the forecastle for a while.

Читать дальше