The sergeant and his team were assets of such importance to the U.S. that the Philippine light infantry company they were instructing had been cut off from the Philippine military’s normal chain of command. It had been placed under the direct control of the Chief of Staff, Gen. Narciso Abaya, a West Point graduate known for his upright character. Only by removing whole levels of bureaucracy was it possible to guarantee the integrity of anything here.

———

My final days in the Philippines were spent at the World War II shrines around Manila. At the American Cemetery and Memorial at Fort Bonifacio (formerly Fort William McKinley) stand the graves of 17,206 American servicemen killed in the Pacific theater in World War II. In addition, on two extensive limestone hemicycles, are inscribed the names of 36,282 Americans missing in action. From the tower of the devotional chapel bells continually peal the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

On the fortress rock of Corregidor, at the head of Manila Bay, stand the monumental remnants of the Topside and Middleside barracks, home to thousands of American servicemen and bombed in 1942 by the Japanese. Each year the moldy wall fragments become more and more like the medieval ruins at Angkor Wat in Cambodia.

Because the Philippines stood at the heart of the fighting in the Pacific in World War II—and because the Japanese occupation was so brutal—the Americans have always been seen here not merely as colonialists but also as liberators. The words inscribed on the Pacific War Memorial on Corregidor may explain why, ultimately, Americans gave their lives in such numbers in the Philippines and lesser known archipelagoes:

TO LIVE IN FREEDOM’S LIGHT IS THE RIGHT OF MANKIND

Yet, it was a long way from those lofty words to the reality of freedom in the Philippines at the time of my visit. Coup rumors dominated the headlines for weeks. The last day that I was in Manila there was a mutiny by 296 junior officers, who seized a shopping mall in the financial district of Makati and ringed it with explosives. Their rage was directed against the rampant corruption in President Arroyo’s government, in which senior officers were accused of selling ammunition to both communist and Islamic insurgents. Moreover, an international terrorist associated with Jemaah Islamiyah, Fathur Rahman al-Ghozi, had simply walked out of his cell at a maximum security facility in Manila after the requisite payoffs had been made to high-ranking Philippine officials. [38] The Philippine Armed Forces later tracked al-Ghozi down and killed him.

Those young mutinous officers were arguably the most idealistic people in the country. They knew that democracy was only a procedural definition for how the Philippines actually functioned. Almost six decades after liberation from the Japanese, and almost two decades after dictator Ferdinand Marcos had been toppled, the Philippine political system was more accurately defined by the compadre network of sordid personal contacts than by any notion of Western civil society. But those young officers were also incredibly naive, for the worst dictatorships can emerge from an excess of idealism.

Not one American noncom or middle-level officer whom I met spoke to me in terms of “saving” or “improving” the Philippines. Rather, these men saw their charge in terms of developing a cadre of Westernized officers and useful contacts in both the Christian and Muslim communities who could be influential even in the event that the state broke up. None of the Americans were cynical, yet all of them were aware of America’s limitations amid vast and roiling cultural and political forces. But they persevered, finding deep personal meaning in their jobs. Soon after I left they found a way to embed individual Green Berets into Philippine units at the battalion level, thus stretching the rules of engagement, so as to better coordinate the hunt for terrorists. Imperial powers know no rest.

CHAPTER FIVE

CENTCOM AND SOCOM

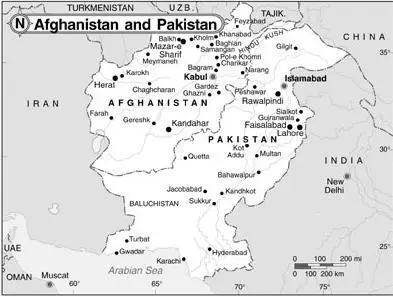

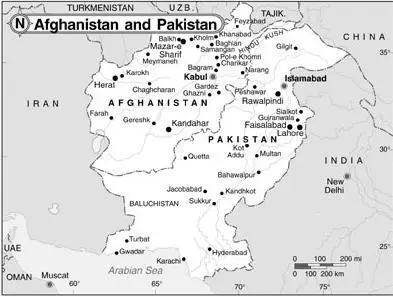

AFGHANISTAN, AUTUMN 2003

WITH NOTES ON PAKISTAN’S NORTHWEST FRONTIER

“Because al-Qaeda was a worldwide insurgency, America had to fight a classic worldwide counterinsurgency… here, amid the field mice and the mud-walled flatness of the Helmand desert, there was only constant trial-and-error experimentation in light of the mission at hand.”

By the time I had returned from the Philippines, the postwar stabilizations of Iraq and Afghanistan were in jeopardy. Both the Pentagon and the American public had thought in terms of final victory and victory parades. Yet the fact that more U.S. troops had been killed by shadowy gunmen in Iraq after the dismantling of the Saddam Hussein regime than during the war itself indicated that the real war over Iraq’s future was being fought now, and Operation Iraqi Freedom—the American-led invasion of the previous March, featuring hundreds of thousands of infantry troops—had merely shaped the battlefield for it.

The low-intensity violence in Sunni-inhabited central Iraq was an example of how the early twenty-first century constituted a universe in which war, to some degree, never ends because it is inextricable from politics and social unrest. In this universe, first defined by the Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz, the military becomes an unceasing instrument of statecraft even as diplomacy remains a principal weapon of war. Such an admixture of military combat and politics means that cultural and historical knowledge of the terrain is more likely than technological wizardry to dilute the so-called fog of war. As an avid reader of poetry and a product of the Romantic age before the Industrial Revolution—an age which respected the primacy of passion over rationality—Clausewitz had eerily intuited this.

But a never-ending state of war was a principle that Americans repeatedly found difficult to accept. Indeed, the first Gulf War in 1991 had seen a complete disconnect between America’s military aims and its postwar political strategy: by abruptly declaring victory, quickly withdrawing its military forces, not creating a demilitarized zone in southern Iraq to weaken Saddam’s surviving regime, and avoiding military links with anti-Saddam insurgents, the administration of George Bush the Elder ended up bolstering the very regime it had sought to undermine during the fighting itself. 1

Now, more than a decade later, with post-Saddam Iraq an exercise yard for unconventional Economy of Force attacks carried out by small groups of hit men and lone suicide bombers, yet another truth was laid bare: the modern battlefield was continuing to expand and empty out, so that it was characterized by a dispersion of forces. 2Massive tank and infantry movements were of less consequence than the lethal actions of a few individuals, magnified by a global media.

In Afghanistan, too, a rapid and seemingly decisive military victory had been followed by a dirty and bloody peace. “Militant Islamic extremism,” wrote New York Times correspondents Amy Waldman and Dexter Filkins, reporting from both Afghanistan and Iraq, was proving to be an ideology that could be “contained but not defeated.” 3Small-scale eruptions of war, with few enemy troops visible, were now a feature of the Near Eastern landscape. It was something the U.S. would have to get used to, whatever party occupied the White House.

The unrest in both countries had different origins. In Iraq, the Baath party, like the KGB and the Communist party of the Soviet Union, had constituted one huge mafia. When the Soviet Union collapsed, the ruling mafia splintered into many smaller ones, leading to low-level chaos for nearly a decade, manifested in crime, murder, and corruption. The same situation obtained in Iraq, except that Iraq also offered significant numbers of U.S. troops as targets. Moreover, Iraq’s sprawling, hard-to-control desert borderlands and its linguistic and ethnic affinities with neighbors like Syria made it possible for al-Qaeda’s foot soldiers to slip inside the country and amplify the threat.

Читать дальше