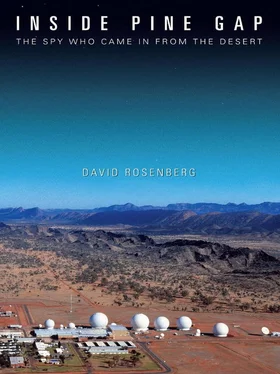

█████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████ and this was the initial, specific purpose for which Pine Gap was constructed. [6] Ball, Pine Gap , p. 16.

This enabled the United States to monitor various weapons development programs in order to prepare effective countermeasures against their use. The treaty formally required both countries to disclose the telemetry frequencies used on their ballistic missiles [7] http://www.dod.mil/acq/acic/treaties/start1/protocols/telemetry.htm

and, although a treaty was in place to monitor telemetry, mistrust to some extent did exist. One of President Reagan’s favourite maxims involving arms control was:

‘Trust, but verify.’ [8] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trust,_but_verify

There are numerous open-source references to Pine Gap’s ability to intercept telemetry, and this supports Professor Ball’s assertion that ‘Pine Gap is an espionage operation’, [9] Ball, Pine Gap , p. 92.

specifically one involving technical espionage. Eventually anything transmitting in the electromagnetic spectrum had become fair game for collection, with the exception of communications involving US citizens without their consent or other legal authorisation as described in United States Signals Intelligence Directive 18 (USSID 18). [10] http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB23/index.html

Similar restrictions apply to Australian citizens.

Decades before I’d arrived at Pine Gap, Russia had constructed weapons testing facilities well within its borders. The answer to the question of how to monitor the testing that occurred at these various ranges was implicit within Prime Minister Hawke’s statement mentioned above. █████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████ As Australia was allied with the United States, Prime Minister Hawke’s statement that Pine Gap ‘supports the national security of both Australia and the United States’ was proven to be true. █████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████ whenever they were positioned against forces that used advanced Russian weapons. The threat of this type of encounter was, and still is very real, as Russian military hardware (and subsequently weapons from other countries) is readily available around the world.

Pine Gap isn’t the only collection facility that provides information to the United States and Australian governments. Likewise, traditional adversaries Russia and China also have their own ground-based, naval and satellite SIGINT collection programs manned by operators who look for signals of interest around the clock. [11] Ball, Signals Intelligence in the Post-Cold War Era , pp. 25–36, 50–6.

The value of these collection sources is recognised around the world, and whether this provides additional justification for the existence of Pine Gap is subjective, but acknowledgement by the highest levels of various governments for the presence of these types of facilities reaffirms their contribution to the security of these nations and their people.

I had read historical data that documented Russia’s pace of weapons testing, but with the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union and the thaw in the Cold War, ██████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████████ as Russia established its new identity around the relatively young independent republics. The intelligence community therefore continued to monitor Russia, as weapons testing and production remained integral to its national identity and security.

Another area of interest to the intelligence community was the simmering war in the Balkans and the disintegration of the Yugoslav Republic as Bosnia and Herzegovina declared their sovereignty in October 1991. Bosnian voters then voted in favour of independence from Yugoslavia in a March 1992 referendum that was largely boycotted by the Bosnian Serbs.

However, the religious/ethnic composition of Muslims (44 per cent), Serbs (31 per cent), and Croats (17 per cent) saw a fight for control from within Bosnia, even as the Croatian and Serbian presidents had planned to partition Bosnia between themselves. [12] http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0107349.html?pageno=1 ; http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0107349.html?pageno=2

The Serb minority within Bosnia, along with the invading Serbian Yugoslav army, began a ruthless campaign of ethnic cleansing—expelling or massacring tens of thousands of Muslims.

While the internal war raged for three years, in August 1995 NATO forces began bombing Serb positions within Bosnia. [13] ibid.

In preparation for this, one of the intelligence community’s roles was to discover whether any of the Serb weapon systems had been modified. It was also important to locate these systems and provide this information to tactical planners; satellites would play a role in obtaining this information.

With bombing taking place, NATO aircraft and their pilots were at risk of being shot down by SAMs that were located throughout the Balkans. To help rescue any downed pilots, the intelligence community actively looked for their search-and-rescue beacons when a pilot was in trouble. Our worst fears were realised when an F-16 fighter aircraft piloted by Air Force Captain Scott O’Grady was shot down while patrolling the no-fly zone during Operation Deny Flight. A Russian SA-6 Gainful missile operated by the Bosnian Serb army is credited with the shoot-down that occurred over Mrkonjic Grad, Bosnia-Herzegovina on 2 June 1995. Allied search-and-rescue capabilities immediately mobilised and listened closely for signs of life from O’Grady and his call sign, ‘Basher Five-Two’, but hope for his safety diminished with each passing day. As it turned out, O’Grady had decided to hide out and delay transmission in case his signal might be detected and located by Serbian forces. Four days later, signs of life appeared when O’Grady’s first transmission was confirmed. ‘He’s alive!’ we chorused with relief. There were many throughout the intelligence community who persisted in looking for O’Grady until he was rescued two days later, on 8 June, by Marine helicopters from the USS Kearsarge . [14] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mrkonji%C4%87_Grad_incident

At Pine Gap we watched the television news and saw the bearded, smiling O’Grady among his fellow soldiers, thankful that his rescue had spared him from being taken prisoner and used as propaganda by the Serbian Government.

Читать дальше