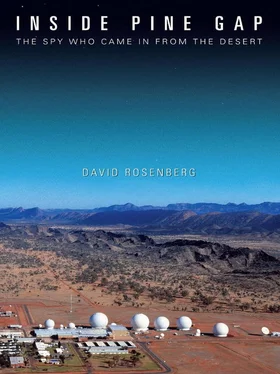

David Rosenberg

INSIDE PINE GAP

THE SPY WHO CAME IN FROM THE DESERT

FOREWORD

by Professor Desmond Ball

Pine Gap is one of the largest, most important and most secret US intelligence collection stations in the world. Specifically, it is a ground control and data processing station for a small number of geostationary signals intelligence (SIGINT) satellites, which collect a wide range of foreign signals, including telemetry associated with tests of advanced weapons systems, radar emissions, other forms of electronic intelligence (ELINT) and microwave telecommunications (providing communications intelligence, or COMINT). The first generation of these satellites was codenamed Rhyolite; its successors have been called Aquacade, Magnum, Orion, Advanced Orion, and Mentor.

The station officially became operational on 19 June 1970, when the first Rhyolite satellite was launched, and operates under an agreement between Washington and Canberra signed on 9 December 1966. It was initially managed by the Office of SIGINT Operations (OSO) of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), under the direction of a super-secret intelligence satellite coordinating agency called the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO). The NRO’s executive role at Pine Gap was officially declassified on 15 October 2008. The ELINT analysts at the station were provided by the National Security Agency (NSA).

David Rosenberg was one of these ELINT analysts. Having joined the NSA in February 1986, he worked in the Office of ELINT, analysing foreign radar emissions. He worked at Pine Gap for eighteen years, from October 1990 to October 2008.

When David first contacted me in early 2010 and told me about his plans to write a book about his assignment at Pine Gap, ‘an insider’s view of what really happens within the Facility’s secure walls’, I expressed my scepticism. This is the station that was originally called merely a ‘defence space research facility’, and which the Minister of Defence, Allen Fairhall, said in 1967 would not do ‘anything of military significance’ and in 1968 was only ‘an experimental project … concerned with upper atmosphere and space phenomena’. Only in 1988 did then–Prime Minister Bob Hawke acknowledge that ‘Pine Gap is a satellite ground station whose function is to collect intelligence data which supports the national security of both Australia and the US’, and that ‘intelligence collected at Pine Gap contributes importantly to the verification of arms control and verification agreements’. In fact, this statement by Hawke remains the most informative official explanation of Pine Gap’s purpose and role ever released. I thought that the intelligence mandarins in both Washington and Canberra would have apoplexy when they learned of David’s intention.

Only one account of experiences at Pine Gap has previously been published by a former employee: an Australian, Leonce Kealy, who worked there from 1970 to 1975. Kealy’s book, The Pine Gap Saga , referred to by David, is entirely different to this one. Kealy worked in the main computer room before Australians had access to the operational areas, and hence was ignorant of operational matters. His story is primarily about the conditions of service at the facility and the discrimination faced by Australian employees, a situation that changed in 1979–80. Since then the Australian staff have had full access to all operational areas, in what David describes as an ‘extraordinary partnership’ between Australians and Americans.

David stresses that this is a personal account, not a technical one. The reader is left with no doubt that he thoroughly enjoyed life in Alice Springs, participating fully in community events and charitable activities, and that he loved the natural wonders of the central Australian countryside—Uluru (Ayers Rock), Kata Tjuta (the Olgas), the flat-topped Mt Connor, Lake Amadeus, Kings Canyon, Simpsons Gap, Standley Chasm, Ormiston Gorge, and Emily Gap, just outside Alice Springs, the ‘special meeting place’ where he went for several years with his wife-to-be, Lou, when she visited him in Alice, and where he proposed to her in 2006.

Nevertheless, this is a revealing book. It describes not only Pine Gap’s ‘general intelligence-gathering functions’ but also the role it plays ‘in support of military operations’. When David arrived at Pine Gap in October 1990, two months after Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, the United States was preparing for military action against Iraq, eventuating in Operation Desert Storm in January–February 1991. Pine Gap is a part of the intelligence community, and he describes the role of providing intelligence through intercepts of electronic transmissions, which included identification of the location of leadership elements and weapons systems and which, coupled with imagery from both reconnaissance satellites and aircraft, provided important information about troop movements and, David believes, helped shorten the war and save the lives of many Coalition fighting men and women. He describes how monitoring the emissions of End Tray radars, co-located with mobile Scud missiles, enabled Scuds to be located.

David recounts searching for various leaders in Somalia in 1993–1994, including Mohamed Farah Aideed; intercepting Serbian military-related signals during the conflict in Kosova in 1998; the interception of communications and weapons-related intelligence just before Operation Desert Fox in Iraq in December 1998; how intercepting the communications of Al-Qaeda leaders had become a high priority by 1998; how, after 9/11, analysts ‘worked diligently assessing Afghanistan’s weapon systems and communications networks’; and Pine Gap’s concerns in the Gulf War in March–April 2003, including analysis of the signal characteristics of Iraq’s GPS jamming systems.

Pine Gap’s most important original function was to intercept the telemetry associated with the testing by the Soviet Union of new ballistic missiles and other advanced weapons systems in their development phase. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, it has continued to monitor the testing of Russian weapons systems. It has also provided important intelligence on the development by China of ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and surface-to-air missiles. David includes a fascinating account of how technical analysis provided ‘key insights’ into China’s development of airborne warning and control system (AWACS) aircraft. He also alludes to the role of the facility in monitoring nuclear and missile developments in North Korea.

In addition to the provision of ‘national’-level intelligence and the support of military operations at the strategic and operational levels, there is sometimes also a personal dimension to Pine Gap’s operations, as evidenced by its involvement to locate and assist the rescue of ‘downed pilots’ by intercepting the signals transmitted by their ‘distress beacons’. On 6 June 1995, for example, four days after US Air Force Captain Scott O’Grady was shot down by a Serbian antiaircraft missile over Bosnia, his distress signal was detected; he was rescued two days later.

I remain amazed that David received permission to publish this story. He does not disclose technical details that might compromise the future effectiveness of Pine Gap and its remarkable satellites but he does relate a litany of activities that would previously have been regarded as being beyond ‘Top Secret’. Publication was approved presumably because this is ultimately a great success story, not only in terms of operational achievements but also in terms of the ‘extraordinary partnership’ that has rendered it so successful.

All of this makes this book compelling reading. It is a subject redolent of mystery and secrecy. It involves the recounting of marvellous achievements and the depiction of an extraordinary working partnership by someone who worked at this exceptional facility for nearly half the period since it became operational. But it is more than just a great read. It is also represents a substantial public service, providing the material that permits an informed public discussion of the value and merits of Pine Gap’s operations.

Читать дальше