Then everyone stood up.

The last time I’d been there I was sitting in our usual spot, on the left side about ten pews back. I turned my head, because I wanted to see if we were still there: Mom, Papi, Estrella, and me. But Buelita Fe was there, staring at me and grabbing her elbows like if she were hugging herself.

The whole time I felt like if she were next to me. Because she could’ve been. So what if she was, kneeling and praying the way she used to when Mom would get up and take communion. I wanted to hear her voice. But all I could hear was Padre Félix and the organ in the corner behind him.

Maybe she had nothing to say to me.

I stayed close to Tencha after communion because I didn’t want to talk to anyone. They’d want to know how I was doing or tell me how sorry they were. They’d tell me that things happen. Accidents happen. Or maybe they wouldn’t say anything at all.

When we were outside, Tía Hilda tried to get me to look at her, but I kept my head down and looked at my shoes, my black Adidas with the word SAMBA on them. Buelita Fe was the only one that didn’t push me. She grabbed my hand and patted it, then wiped my face like if it was dirty, and now it was clean. When I smelled her dishwashing soap on her hands, it was like my insides started folding and I started crying, keeping my mouth shut so they wouldn’t hear me.

In the car on our way back to the center I wanted to tell Tencha I was sorry for not wearing the dress she bought me. I was sorry I didn’t want to go to the cemetery or the reception. But all I wanted was to go see Papi. She kept driving and looking forward like if there was nothing else to do but go back to the center.

Then I said something, something stupid that came to my mind. It was the first time I opened my mouth since it happened. The first time I said anything.

“Why don’t we go back to Mexico?”

She paused for a moment, looking at me then back at the road. I guess she needed a moment to realize that I’d spoken. She tried not to make a big deal about it. Like if she knew all along it would come. “I love you. Lo sabes, ¿verdad? ”

“Yeah,” I said.

“But why would you say that?”

“Because.” I looked at her and wiped my face.

“You want to go to school in Mexico and leave your Papi? Is that what you want? I love you. You know that, right? But you don’t want to go back to Mexico,” she said. “It’s better for you here.”

I looked down at my lap with my palms over my thighs. “It doesn’t mean I don’t love her,” I said.

“I know, mama,” she said. “I know.”

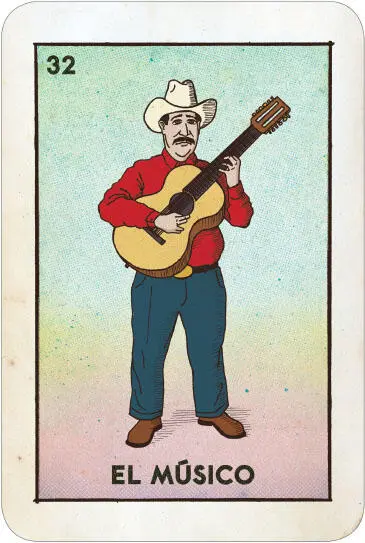

There was a singing competition on Siempre en Domingo for kids. We were sitting around the television at Buelita Fe’s one weekend, rooting for the ones we thought should win. Some of them came out wearing dresses like holiday decorations. They shimmied their shoulders and couldn’t sing to save their lives, but because they were show-offs they got a lot of applause. One little boy came out dressed as a mariachi and sang a Tony Aguilar song, singing as strong as a rooster with a voice that got everyone’s attention. Buelita Fe said she’d seen an interview with him earlier that day, and his name was Federico. He was from a town in the middle of nowhere and was real poor. This was his big chance. His mother and father asked the church for money so he could get to Siempre en Domingo for the competition. In the interview he said, “This is for my mother and father, because we don’t have any money. We only have one bed. If I win, I’ll work hard because I want us to move out of our small house. I want to buy my father a truck so he doesn’t have to take the bus anymore. And maybe on weekends, we can go to the beach.” Buelita Fe was crying by the time she finished telling us.

I looked at Papi and asked, “Why is she crying?”

“Because,” he said. “She cries at everything.”

“But what’s so sad about that? He’s good, he’s probably going to win.”

“He wants to buy his father a truck. And he wants to go to the beach.”

“That’s why she’s crying?”

“Yeah, that’s why.”

I listened to that boy sing. He stood with his arms down next to him and looked out to the audience with his eyes full of everything his mom and dad had taught him. When he was almost done, singing his last note, making a face like if he were trying to lift a car, I felt something light up inside of me. Not because he was poor or because he wanted to go to the beach but because his voice was so strong it pressed in the middle of my chest. When the song finished, Buelita Fe dried her cheeks with a bunched-up tissue she’d been holding the entire competition.

Mom was the last one to close the door, looking over her shoulder, as if to remind me, “That’s what you get for being una chiflada .”

I didn’t want to play with Estrella’s friends anyway. It was her birthday party. She turned twelve and all the presents were for her.

I was on my third cheeseburger when I saw the man walk in. He had a gym bag over his shoulder with red Bozo shoes on. He walked straight to the bathroom in the back of the restaurant, and ten minutes later he came out as Ronald McDonald with white makeup on and a red afro. When he passed me, he winked and said, “Our secret, right?”

I could see the stubble under his white makeup and he smelled like bacon. He thought I was playing along, but really, I didn’t care. He leaned over and asked who the birthday girl was. I looked outside. Estrella and her friend Angélica were swinging on a chained tire. Other kids were running around, screaming, “You’re it! You’re it!” Mom and her friends were sitting in their hips, looking at the highway. A girl with thick glasses sitting at the end of the monkey bars reminded me of La Chilindrina from El chavo del ocho , except she didn’t have any freckles. She lived on Market, in a red house that didn’t look like the others. Estrella didn’t hang out with her and neither did I. I don’t know how she was invited. Mom probably told her, because she wanted us to be friends with her.

Chilindrina was looking at us. I took a bite from my cheeseburger and pointed at her. With my mouth full I said, “The girl with the glasses.”

Ronald McDonald stepped out onto the playground and spread his arms open like an airplane. He had a paper crown around his elbow, gold with ruby stickers on it. Estrella ran toward him but he walked past her and straight to Chilindrina. He took the crown from his arm and placed it over her head and must’ve said Happy Birthday, or something. He grabbed her with both arms and lifted her off the wooden deck. Mom walked toward him, shaking her hand, while Estrella grabbed the crown and put it on. Then they turned, and he pointed at me.

I ran to the handicapped bathroom and locked the door and waited for an hour before I came out. By then I figured the coast was clear. When I walked out Ronald McDonald was sitting in a booth with his wig on the table. And when I walked past him I stuck out my tongue. “Our secret, right?” I said.

Nothing outside had changed. Everyone was still playing the same games as before.

On the table where I was sitting was the bent, deformed crown that was supposed to be for the birthday girl. I put it on and went outside and climbed the wooden deck, sat down next to Chilindrina and asked her if she’d ever seen El chavo del ocho.

Читать дальше