When she opened her eyes again, Arnold and Lilldolly were drinking coffee on the pelt next to her.

“You fell asleep in the sun,” Arnold said. He handed her a knife and a piece of dried meat he’d been carving from.

“Eat!” he told her. “It’s salty. Good for you.”

She pulled herself up into a sitting position and cut off a small piece of meat.

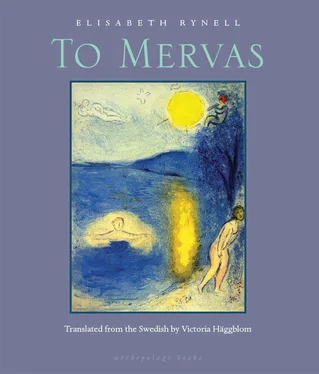

“You see, we’re talking about Mervas,” Arnold continued. “We’re wondering if we should go on that excursion tomorrow. On the radio, they say the weather’s going to be nice now. Lilldolly says it too; summer’s here now, she says. So we’re considering taking tomorrow off and heading up there.”

Marta nodded. She felt confused. Mervas, she thought. Would it become real now? For real? Perhaps she ought to go there alone? She wasn’t sure. But if Kosti was there, if she was going to meet Kosti, did she want Arnold and Lilldolly to be there too? No, she wasn’t sure.

She nodded again.

“It’ll be fun,” she said.

Arnold laughed and looked from Marta to Lilldolly and then back at Marta again.

“Well, let me tell you, it’s been a while since we went anywhere. There was the dental appointment last winter, of course, a couple of tooth extractions and such. The pharmacy, perhaps the social security office.”

“And the grave,” Lilldolly added. “We went to the grave.”

He seemed taken aback, paused for a moment.

“Yes, the grave. We do have the grave, Lilldolly and I.” He inhaled.

“Yes,” he said, focusing on Marta. “You see. That’s how it is. It was a good thing that you got lost and ended up here. This way we get to go on a little trip before we get stuck to this place like moss on the rocks.” He laughed again.

“We can go shopping too,” Marta said. “And to the grave, if you want. Now that we’re going.”

“No, that’ll be another day,” Lilldolly decided. “Mervas is in the opposite direction altogether. That’ll be a whole other trip. No, let’s go to Mervas. That’ll be something else.”

She peered at Arnold.

“Yes,” he said. “It’s another world. Mervas.”

After some discussion, it was settled that Arnold would drive. He was the one who knew the roads the best and was used to being on them, he argued. Lilldolly wanted to sit in peace in the back and have space for her own thoughts and Marta would sit in the passenger seat. She’d have a good view from there and that was important, Arnold reasoned, because she had to learn the way to Mervas. Tasso was also coming along, and he got to sit next to Lilldolly in the back, as he used to. They put sheepskins, food, and the coffeepot in the trunk. Then they took to the road.

Arnold was driving fast, Marta thought, but she didn’t say anything to him about it. After Deep Tarn’s road, they’d ended up on a narrow gravel road that wound through a steep, undulating forest and small ponds like hollows strewn everywhere in the landscape. The spruce trees were sparsely spread; no shrubs or low trees obscured the view. Here and there, a big boulder covered in gray moss rose from the ground. Small ridges pressed against the ground like the backs of animals. Without warning, the trees came to a halt at a gorge that led straight down to another kind of world. Here, everything seemed small and inviting. You wanted to enter among the trees and walk around in those woods. The ground seemed to be padded; perhaps the huldra * moved there on her soft, springy paws.

But suddenly, the narrow road ended and Arnold veered right onto a wider gravel road that cut straight through a landscape that was completely different. Vast and endless, it stretched out with its enormous lakes resting in depressions between the mountains. It was mostly woods and no vistas, young trees and old growth, the sun like a golden caress over the carpet of berry shrubs between the trees. Sometimes they came upon clear-cuts, large, empty areas, but these areas were forests too — missing, petrified forests without trees, woods in waiting.

They didn’t talk during the trip. It was still early in the day and night hadn’t yet wholly left their senses. They sat focused, looking out the windows, and stayed silent while the road crunched beneath them and the landscape rushed past. The road continued straight and wide and they passed yet another big lake. Marta thought there was something odd about these large, desolate bodies of water; there were no houses around them. They just lay there as if undiscovered by man. Nowhere had they seen a single house or farm. Only in one place, in a small clearing by a little lake, was there an abandoned trailer. They traveled through the woodland as if they each had their own small part in it. Mile after mile it belonged to itself; trees and animals and people were nothing but visitors there.

The sky was a blue stream lined with the tops of scraggly fingered firs, floating above the road. Marta looked up, following the stream; it was easier than trying to look into the forest. The trees obscured the view, she thought; they were in the way. It takes time to discover that the forest is a place where the space between things matters more than the trees, that it is a swaying in-between world where light and shadows rule. Someone is playing an instrument in there, sometimes slow and gliding, other times jerky and bouncy, a bow of light and shadow slides across the strings of all the tree trunks and branches and twigs. If you want to see the forest, you have to avoid looking at the trees; you have to learn how to look where there’s nothing, to the side. That’s when you hear the music.

Marta’s internal view was also obscured today; inside her, the trees were also in the way. She saw the calf with its crushed, hanging head and thought about Lilldolly and Arnold, thought about what Lilldolly had said the first night she met them, that with this man she shared neither table nor bed. She was now sharing the place where she slept with Marta. But Arnold and Lilldolly seemed like a couple in any case. They didn’t seem to be enemies. It was obvious they liked each other. But still, Lilldolly’s story had pushed Marta into a place she couldn’t escape; something tugged at her. She was caught up in scattered thoughts about the boy and Anna-Karin and the calf, about Mervas and Kosti. Caught up in sudden fragments of childhood memories that kept appearing — her father’s spirit inside her, his constant, commanding presence, the fear of his voice raging through the mail slot. Then, her mother’s austere features, immovable and stern, enduring it all. She remembered her own feeling of being on fire and freezing simultaneously, of being completely naked and walking powerless across the floor of the stage, of existing without form. She had to be there, had to be there. Caught up in all this, she desperately tried to see over the edge of her own life. But the blue canal above the road flowed through her like a ribbon of forgetfulness, a blue thoughtlessness, a blue oblivion free of longing. It told her she didn’t have the strength to figure out what the chafing images and memories had to do with her. It told her she didn’t want to know if they were about her life. Or about herself. She really didn’t even want to know that they were now on their way to Mervas; she’d soon be there, very soon she’d actually be there.

They’d just passed another lake and come up on an elevated plateau when Arnold suddenly, in the middle of a steep upward slope, slowed down and almost stopped the car.

“Here’s the road up to Mervas,” he said. “It’s easy to miss. You can barely detect it.”

“We’re here?” Marta asked, newly awake. “We’ve arrived?”

“No, we’re not there yet, but this is the road. It’s about two kilometers, as I recall. A lousy road.”

Читать дальше