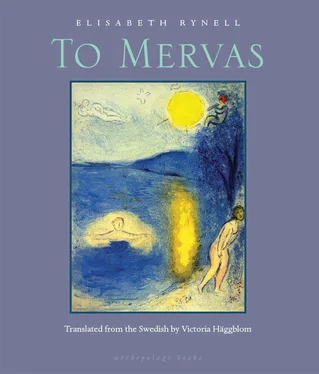

Elisabeth Rynell

To Mervas

Life must be a story,

or else it will crush you.

I’ve been thinking that just like a fire,

a story too has its place, its hearth.

From there it rises and burns.

Devours its tale.

A letter came. Just a few lines, jotted down on a piece of copy paper.

Marta, Mart! I’m in Mervas. It’s not possible to get any farther away. And no closer either. Your Kosti.

That’s all it said. And he hadn’t been in touch for over twenty years. Not that I’ve been counting the years; I stopped doing that a long time ago. But now he’d sent me this message and it was like being filled with air, like being hit in the face by a gale so strong it made me gasp for breath.

I read the letter again and again. My first thought was that it was fake, that someone wanted to taunt me. But who would want to do that? I have no friends; there’s no one who would know that such a cryptic little note would weigh on me. No one, except perhaps Kosti himself. And now he had written it. A faint cry from one end of life to the other, a cry straight through the years. And from Mervas. What kind of place was Mervas?

I wept. A sadness so vast washed over me I wasn’t sure I’d be able to contain it. In some ways, it was myself that I mourned. I mourned my own life; it was as if I’d been invited to my own funeral and now stood above the coffin, where everything had been completed and settled, where for the first time my life could be looked upon as something finished and concluded, and there was nothing, absolutely nothing, that could be added to it. And I cried over everything that was lost, everything that had gone wrong and been led astray. My tears were unnaturally hot, they ran down my neck and onto my chest and I felt their entire path, felt how hot they were, strangely, remarkably hot, as if there’d been boiling, volcanic wells hidden inside me, and now they were overflowing through my eyes.

To keep from falling to pieces, I started pacing. I covered every room. The small, dismal apartment became a dreamscape. My tears made everything blurry, almost blotted things out, and in this intense and charged absence, I reached for objects like a blind person. I used my fingertips to see, my eyes were elsewhere.

I must have plodded for hours. The entire time, I thought I would implode from sadness, that I would break like a clay vessel in pressured heat. I touched potted plants, rocks, books, furniture, and lamp shades. It grew darker in the rooms, I could sense the gloam through my skin. The midday gray seeped inside and settled on the floor, the walls, and grew denser.

In my head echoed the idiotic little saying “A letter means so much.” I couldn’t get rid of it; the insinuating voice followed me wherever I went. I knew that the letter I’d received wasn’t much of a letter, but still, the few words he’d written were alive inside me, they’d awakened and shaken me, struck me with something I’d nearly lost. They’d reminded me of my life and the fact that I was still living it, that I was supposed to live it. I’d forgotten that. I’d stayed away from that truth. And a person can actually hide inside her own life, hide from life itself within the minutiae and everyday chores, hide from herself inside herself. She can do it, I know this, I knew it even then, but I didn’t pay it any mind.

Finally, I went to the bathroom and turned on the light. Avoiding my reflection in the mirror, I filled the sink with cold water and submerged my hot, tear-swollen face. I held it in the ice-cold water until it ached. Then I straightened slowly and met my image in the mirror. I have never liked my face; I’ve somehow never been able to pull it together. Here it was, large and unignorable, looming in the mirror like an approaching storm. It was an old face, I could see that. Ugly. The ugly face stared back at me and simultaneously, in an alarming maneuver, crawled inside me and stared out at itself. I was old and ugly and here I stood. A letter from the other end of time had arrived and the blind and complacent one-day-at-a-time existence I’d been living for so many years had instantly burst to pieces. Instead, I now held my entire life, my whole story, in my arms, and it looked like a skinned animal, a skinned yet still living, struggling animal. I shook from holding it, shook from the very core of my being. And as I stood there, the thought went through my mind that I’d waited for him my entire life. My whole adult life I’d longed for him, kept a small place ready, a little backyard, a secret, hidden place for him, for Kosti. I knew that this place had been the only one that mattered, the one thing that had kept me alive, even though I myself didn’t even know it existed. Now I’d discovered it. I’d caught myself in the act. I too had been carried along by a dream. Simply being alive isn’t enough. Perhaps that’s how it must be.

I stood captive before the bathroom mirror and stared into the face that was supposed to be mine. Once you get lost in your life, I thought, you just keep getting more and more lost. Meanwhile, the years close in on you like a thick forest. They tangle and grow denser, they become tangled forests of years.

The apartment now lay in darkness. Mervas, I thought dimly. What kind of place is Mervas? I stood in the kitchen and the lamp over the kitchen table was lit. His letter lay there, exposed. Written in blue ink. I’d avoided letting my tears fall onto it. He’d always used blue ink that tears could dissolve. Your Kosti, it said. Your Kosti, he’d written. How could he? Only those who are truly alone know what it’s like to be a lost child in the world, a lost child in a great war. But all of us are alone, more or less. Someone lost us along the way. With my hands still trembling slightly, I refolded the paper and put it back inside the envelope. No more tears were coming, no hot tears. The wells had evidently dried up. All I felt was a dry cramping in my chest, a feeling of something inconsolable draining me, feeding off me. I wasn’t feeling sorry for myself, I think, not even then. I’m not worth pitying. But my life hurt inside me. It moved like a child, like a fetus inside me, a bundle of hammering, kicking willpower. This is unbearable, I remember thinking. Only that single word: unbearable.

Somewhere in my life is a city shrouded in darkness. It’s a big city, probably a capital. All roads lead to it, into the dark, where they dissolve. I know this city exists, that like all cities it has houses and streets, that a kind of living takes place there, stories are formed, meetings and scenes. But nothing can be distinguished in that darkness. It is like a mute weave that has been pushed into the center of my life, thread upon thread of silence. And I’m afraid of this darkness, I know that from it, anything can break through: a bright, blind violence, a rage like a forest fire igniting even the air. There are monsters living there that have courted me, monsters that hatch in darkness, and I don’t want to see them, don’t want to know about them. Sometimes I imagine that the city gulps down the darkness, that it greedily fills itself with more and more darkness and grows, swells — and in this way, it is active, a volcano in reverse. A crater that drinks and devours rather than spewing things out.

Standing there by the kitchen table looking at the envelope where I’d just put Kosti’s letter, I suddenly caught a glimpse of the dark city, as if it had been illuminated in a flash of light. A bright white sheen pumped through it like a heartbeat, and I realized I had to enter it, perhaps it wasn’t always sunk in darkness; light could blow into it, a wind of light.

Читать дальше