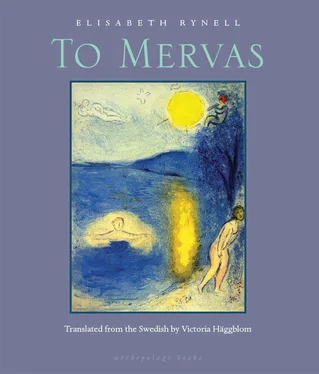

“By midsummer, lilies of the valley will be blossoming here by the tarn,” Lilldolly said when they carried blueberry branches inside the cabin. “Tons of lilies of the valley. Then you have to come and visit and pick some!”

Marta never felt as lightheartedly chatty as Lilldolly. In some way, she was speaking the wrong language, and she felt everything she said sounded artificial and stiff, like a newscaster on television. Arnold and Lilldolly spoke as if they were in love with every word and expression they used; as if they caressed them inside their mouths and shamelessly enjoyed using them.

“My, it’s fun to have company,” Lilldolly now exclaimed. “Even to haul out the sour dung to the potato field! Now, let’s see if we can get the woodstove here going, so we can make some coffee.”

She’d already started a fire that was snapping and crackling behind the stove door and the coffeepot jerked suddenly from the heat on the burner.

“Yes, out here, we’re on our own,” she continued contently. “Just you and me.”

They were sitting on two small stools by a little table attached to the wall right by the stove. Lilldolly took out a piece of the tart-smelling cheese, a vat of butter, and bread cut into triangles. There were cups in the hut and she’d brought sugar in a little bag. They were quiet for a moment while waiting for the coffee. The low door was open toward the water, and on the other wall, the only window in the hut looked out over the forest. It was too early for mosquitoes, and the only sounds came from the birds outside and the low murmur of the woodstove.

Lilldolly settled her searching, vibrant gaze on Marta, carefully studying her, sort of feeling her way across her face little by little.

“This is a good place to talk,” she said. “After all, we haven’t told each other very much over these last few days. You don’t say much, do you? You keep things close to yourself.”

She turned the stool around and dealt with the coffee, pouring it into cups and continuing:

“I can see you’ve got your own story. It’s the story that brought you here, and that will take you up to Mervas. I’m not blind, but I’m not going to question you about it. Anyone has the right to keep as quiet as they like. I’m a curious person, of course, but not so much that you have to tell me. You can keep quiet if you want. If you want to talk about yourself, you’re welcome to. But stories have to come on their own accord, they’re alive like everything else. If they’re going to come out, they’d better come out alive, otherwise there’s no point.”

Marta felt hard and mute during Lilldolly’s speech. When she lifted the coffee cup to her lips, she noticed that her hand was trembling; from the corner of her eye, she saw that Lilldolly had noticed too. She desperately tried to think of something appropriate to say, but there was nothing to say, she found nothing. Somewhere inside her, there was a small rupture, a faint desire to place her life in Lilldolly’s hands, to simply let her receive it.

“But if you don’t want to talk, perhaps I can tell you something? It’s something I’ve never told anyone before, not in its entirety at least. It’s not a secret I want to share with you; it’s just that it so rarely happens that someone I can talk to comes here. I really feel the urge to tell you, if you want me to, if you want to hear it.”

Marta nodded. Of course she wanted Lilldolly to tell her, she wanted it very much. She couldn’t remember the last time anyone told her something important, had it even happened before? Yes, of course it had, but a very long time ago. She now sensed something resembling undernourishment. Her life was arid and gray, lacking in stories, people, and fairy tales. This meager existence had made her thin and weak, sort of translucent.

“Yes, please tell me,” she said at last, smiling uncertainly at Lilldolly. “I mean it. Tell me. It doesn’t happen often to me either. I mean, I’ve lived alone most of my life.”

Lilldolly chuckled, placed a lump of sugar in her mouth and let it dissolve as she sipped her coffee. After this, she put butter and cheese on the bread and chewed and ate for a while. Outside, an osprey shrieked high in the sky, and Marta sat with her hands in her lap letting the stillness envelop her. She had made the right decision setting out on this journey, she thought. She had not been brought off track.

Humans are so careless. That’s the worst thing about them. They’re so impatient, so rough. Why are they in such a rush? What drives them? Why are they grabbing things so angrily, always causing harm? They push and pull their poor animals instead of sitting down, listening to them, and talking to them so they can feel at ease. It’s as if everyone is walking around with a constant storm inside; there’s always a headwind inside them, always pouring rain and hail. They trample gentle flowers, tear up moss from the ground in big chunks. They clear-cut the forests as if there were a war going on and everything had to be obliterated. They are so harsh, everywhere and with everything. Children get slapped and banged around. The very earth itself gets skinned and dismembered as if it were a slaughtered animal, nothing but a dead, numb, lifeless body. All this brutal ravaging has made me afraid for life; it has somehow injured and hurt me deep in my heart, at my core. It’s as if everything that’s beautiful, wise, and simple has been stepped upon, stomped upon. You know, everything beautiful in the world goes straight to your heart as surely as the birds come flying here in the spring. Beauty is reflected in the heart, it places its reflection in our hearts as true and as real as you see the forest reflected here on the lake. Of course you think I’m being childish. But I’m old too, I’ve lived a long, long time and have been able to think these things over so many times that I know they’re true. I’ve also experienced how all the mean and ugly things in the world have argued with my heart, pierced it so I’ve had to defend myself with all my might. Yes, I’ve learned, I’ve learned that the only thing worth listening to is the longing, my own longing, my heart, you see. That beautiful call inside me is the only thing worth listening to.

Lilldolly’s a bit weak for the animals, isn’t she? That’s what they said when I was a girl and didn’t want to come into the woods and watch the reindeer be slaughtered. Or when I ran away at the mere sight of my father returning home from a hunt with quails and rabbits hanging dead from his belt. The rabbits were hung on the wall, their big black eyes staring empty, and their long soft ears now useless. I used to sneak out to them at night and tell them I was sorry they’d been shot and cut open, their bellies filled with prickly spruce needles. I’ll help you, I told the rabbits. When I grow up, I’m going to help you, I said, still believing that when a person grows up, they can do whatever they want.

But I did eat the meat after all, it was like that in those days, you ate what was put on the table. Sometimes there wasn’t much of anything. No. But that wasn’t what I was going to tell you about; this was mostly an introduction of sorts because what I was going to tell you happened when I was a married adult.

You see, Arnold and I, we couldn’t have children. It was as if fate had decided we weren’t going to have any, we were forced to live without little ones even though we longed deeply for them and sort of had waited for them during the years we’d been together. We were already living here in Deep Tarn, it was where Arnold grew up and his mother was still alive and lived upstairs in her chamber like a spider guarding her web. God Almighty, that woman blathered so much nonsense. She said that Arnold ought to find himself another woman so that there’d be children on the farm. She said worse things too, things that made me say no when she wanted me to bring her food upstairs when her legs were too weak to come downstairs. And let me tell you what I think. I think Arnold’s mother was a real witch. She put the evil eye on me because I’d taken her sweet boy away from her. As long as that hag was alive, no children were conceived in Deep Tarn. She lived for a long time too. Goddamned stubborn she was, almost rotted completely before she stopped breathing and died. She rotted both inside and outside, her body and soul. Yes, curse her! But finally, she was dead and then she was buried and after that it didn’t take long until I got pregnant. I was right, I said to Arnold. I couldn’t help myself, I had to tell him. Now you see that I was right, it was that mother of yours who kept us from having children! Arnold said there was no way of knowing if that’s how it was. Children come of their own accord and there’s no way we can know what they think, he said, and then we didn’t speak about it anymore. She’d been his mother, after all, and he didn’t like anyone but himself to be speaking ill of her. She was also dead and gone now, the room where she’d lived was scoured clean and repainted and all her old rags had been burned.

Читать дальше