That’s when she saw that they were just about to pass an almost illegible sign that leaned toward the low birches behind it. She surmised the name more than read it; the sign was flecked with rust, half-eroded and erased, but it burned inside her like a branding iron. One by one, the letters of this name burned their way inside her and now she held the letter in her hand again where she’d first read it; now she felt the triumph she’d experienced when these same letters had appeared in the right order in the index of the big Nordic atlas in the library.

“I can’t do it,” she said at once with such determination that Arnold immediately hit the brakes and stopped the car.

“I can’t do it, I have to go there by myself,” she continued. “I have to do it alone.”

Arnold turned and looked at her with his iridescent blue eyes and she thought she’d corrode under his gaze.

“So we’ll have our excursion somewhere else today,” Lilldolly called quickly from the backseat. “We’ll go to Reindeer Head Rapids today!”

“I’m sorry,” Marta said.

“You don’t have to apologize. I thought you’d have us step out here in the middle of nowhere while you’d go up to Mervas by yourself. All right, let’s go to Reindeer Head Rapids. Absolutely. We used to do that all the time in the old days, Lilldolly and I, when our little Opel was still running. Yes, we’d go to Reindeer Head Rapids every spring.”

He backed up a little too fast from the road to Mervas and then pressed so hard on the gas that Tasso started barking with excitement.

“Hush, silly,” Arnold shushed. “You’re frightening the girls!” He peered at Marta and smiled a little. “I say, you’re a difficult one,” he said.

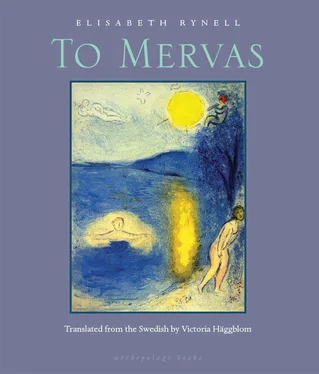

A week later, Marta found herself again in her car before the sign that had once pointed toward the mining community Mervas. Now it pointed mostly toward the low shrubs, down toward the ground.

She’d stepped out of her car and stood there staring. The solitude pressed against her, the silence pounded in her ears. The only sounds beyond her own were the wind and the hum of bird voices. The road to Mervas was very narrow, saplings crowded the edges and soon they’d start growing in the middle of the road. The budding green birch trees arched like a tunnel above her and light glittered through the braided branches.

She took a few loudly crunching steps onto the road and discovered that she was walking on asphalt, on cracked, shrinking asphalt. She shivered as if someone had touched her unexpectedly and could imagine what the road must have looked like once, before the woods started closing in from both sides, before the frost from below could freely gnaw it to pieces and partly swallow it. It had been blank and glossy and wide, with a demanding parade of yellow lines running down the middle, and like a general it had brought people through the desolate forests and wilderness into the new and neatly organized place that Mervas had been.

Now the silence was incomprehensible. Trucks and buses and cars had driven here, clusters of children and teenagers had biked down this road, Vespas and mopeds had sputtered down it. In some strange way, it felt as if all these things were still there, as if they’d been preserved and were still occurring somewhere below everything, hidden. Marta kicked the gravel a little as if to resist the impulse to shout to the past, to call out a sorrowful greeting, a lonely hello. She realized that her present was shared by a past that had, in a sudden gust, breathed on her.

Saturated, she walked back to the car, got behind the wheel, and began driving toward Mervas. Branches scratched the car’s paint with sad, faint sounds. She didn’t take her eyes off the unreliable road, riddled with potholes and rocks and fallen branches. She was forging a track, and she could feel it within herself. It had always been there, a creek, a flowing body of water inside of her; now it had surfaced.

Something large suddenly appeared in front of the car. Startled, she slammed the brakes before she had time to see what it was. It was a reindeer, nearly white, standing but a yard away from her. For some reason it refused to move; it stood glowering at her for a while and then started an easy trot up the road. Marta had to follow slowly behind.

She thought she’d been driving forever when the dense old-growth forest suddenly cleared around her. The reindeer was still running ahead of the car when she came into a birch forest with a patch of grass in the middle, almost like a rotary. The reindeer went to the right, down a slope. Marta stayed in the intersection, trying to figure out where she’d ended up.

A very sparse pine forest surrounded her and soon she discovered, both straight ahead and to the left, a residential area; except there were no actual houses. The foundations were lined up in neat rows, partly overgrown by moss and berry bushes. Staircases and basement windows were still in place. Since no houses obscured the view, the grid pattern of the streets was visible between the trees. A small flock of reindeer was grazing among the remains of the foundations. The scene was so still, so strange. Marta parked on the nearest street. Then she opened the door, but stayed in the car. This silence, would she ever get used to it? It was so serious, so demanding. Each and every little sound had to be let through it, nothing could escape, and the world seemed as close as skin against skin; everything was laid bare.

Mosquitoes flew inside the car; they had hatched in the recent heat. She shut the door. It felt difficult to step outside; the solitude ached inside her. Sooner or later she’d have to go out. Her fear battled her curiosity; she had to go out. The reindeer probably wouldn’t attack her; she’d never heard of that happening. If they weren’t afraid of walking around here, she shouldn’t be afraid either. There couldn’t be any bears around if the reindeer were here. Arnold had talked about bears and blueberries, but he’d never mentioned any reindeer.

She took a deep breath, and then stepped out of the car, closed the door, and turned her back to it. Her heart pounding, she looked out over the abandoned community. It appeared to her as idyllic as the neighborhoods of nicely decorated wood houses common in Swedish small towns. But the place also exuded something else. Like a piece of dynamite ready to explode, something was constantly threatening the village’s idyllic sense of sleep and stagnation. She sensed a presence, a very strong presence, palpable like a wall — the sensation of a body, a voice.

She forced herself to start walking. To avoid disturbing the reindeer, she walked straight ahead for a block and then turned onto the first street to the left. After about a hundred yards, she came upon the remains of a big building where surprisingly many of the walls were still intact. A cracked staircase led her down to the basement floor and she stepped through a door hole into the largest room. A great willow tree was in bloom there. The corridor behind the room had door frames that all opened to the woods. All floors and ceilings were gone and the ground inside the building was covered by last year’s leaves. On a wall in the corridor, someone had written: I went to school here from 1946 to 1952. There was an illegible name underneath, Astrid something, and a date from an earlier year. Others had written and scratched things on the walls too, but the text had faded.

She continued her walk up and down the streets. Everywhere were signs of habitation, moss-covered columns stood silent among the fir trees, foundations and collapsed basements, small houses and larger buildings. Right where she’d left the car she found the communal laundry room and its cast-iron washtubs. Here, the roof was intact, but a pile of rocks and mortar had sealed the front door. She stood looking in through a window, an oblong, square opening in the moss. The sun had found the same opening and illuminated the floor and the walls with its warm yellow light, a stream of honey on the gray stone. Shards of mortar and concrete covered the floor, and the cracked walls were covered with mold. But no objects were to be found, not a single thing had been left behind. You could tell that this place, this little town, had been abandoned in a very organized way. Even in its deterioration, the precise, businesslike order that had once ruled here was still very much present. A sort of bottomless rationality, an organized decay, seemed to surround her. All appendages had obviously been cleared away before the houses were disassembled. Windows and doors with frames had been removed; furniture, toys, buckets, and kitchen appliances had been carefully cleared out. Only the foundations that would eventually wither away had been left behind, the remains of stairs, the window frames. Mervas was a skeleton that had been picked clean.

Читать дальше