Jean-Louis Arambel, nineteen, is the youngest of the group from Aldudes. He leaves behind his parents and three brothers. It will mean one less mouth to feed, and he is hoping for a better future. There won’t be tears at his departure. He plans to live with his uncle, a farmer in Los Banos, California. His sweetheart, Maritchu, to whom he gave a long kiss the night before he left, will surely wait ten years for him. They have sworn a solemn promise to each other and sealed their pact on the crest of a hill. When he comes home, they will buy a piece of land together, down below, in the valley.

Jean-Pierre Aduritz has less to lose and little to gain. But he’s going. At twenty-one, he has been a domestic servant in Aldudes since the age of five. The shepherd’s contract he has in his pocket is enough to make him happy. His four sisters can maybe join him over there someday. At least he hopes so.

Jean-Pierre Suquilbide, twenty-five, a servant like Aduritz, is the eldest of seven children. He is not particularly ambitious, but he is glad to be going to Pocatello, Idaho. He wants one day, in ten years maybe, to buy a white house in his village. He has met them in the shade of the pelota courts, the elders who returned from America, and has heard their stories of horses, of cowboys, of vast grasslands in Wyoming, Texas, Colorado. They even spoke some English for amusement.

The five young shepherds are emigrating so as to come back, leaving so as to settle later in the valley, a huge detour, the only solution open to them. Their hope is to find the cousins, brothers, friends who went before, the famous shepherds who exchanged trails through the Pyrenees for other, unknown mountains on a ranchman’s contract of ten, fifteen years, after which they returned home, wealthy and proud, to become, in the villagers’ eyes, “the Americans.”

Basque shepherds had earned a good reputation, were known for their love of work and animals. Landless shepherds in their own country, they found tracts of land on the boundless frontier to clear and cultivate. The vast distances were new to them, the seasonal migration stretched over several months — winter in the desert, spring at an altitude of almost ten thousand feet. The salary was $170 a month, and the currency was strong, with the exchange rate at 350 francs to the dollar. Hundreds of shepherds and farmers from the Basque country immigrated to the United States in the decades from the 1930s to the 1960s, forming a Basque diaspora. They retained their language from across the Atlantic, a unified community, improvising matches of pelota in the barns of the New World. Some never returned, some married there, some died in the United States. Ohore zuri euskal artzaina , “All honor to you, Basque shepherd,” would read the epitaph, or else these verses by Grégoire Iturria:

Tranpa gorria

Hunarat etorria

Untsa urrikitia

Fitesko hustu behar tokia .

Coming here

Is a trap

A regret

A place soon to be left behind .

In the train, the five shepherds, escorted by M. Monlong, talk loudly back and forth. The three Jeans from Aldudes — Jean-Louis Arambel, Jean-Pierre Aduritz, and Jean-Pierre Suquilbride — joke with one another as distant relatives do. The three villagers soon find that they share a cousin with Guillaume Chaurront and Thérèse Etchepare. In the valley, everyone is family. The shepherds’ compartment in the second-class carriage echoes with the local dialect of the Quint region, on the border of Navarre and Lower Navarre, featured by Prince Louis-Lucien Bonaparte in his Map of the Seven Basque Provinces , published in 1863. They sing airs from the home country, with Jean-Louis offering a chorus of “All summer long, the nesting quail sings his sweet song.” The sadness of departure, the nostalgia for their home valley, is displaced by the foretaste of the great adventure ahead, of the internal boundaries dropping away as they advance. Behind them are the 920 residents who stayed, the pelota courts, the white houses with brown doors and shutters, the landscape divided by the Nourèpe, the village’s river. They talk about the airplane, about flying, how crazy it is.

At the Gare d’Austerlitz, the five youngsters and their chaperone discover Paris for the first time. From their base at the Hôtel du Terminus, they pore over a map of the city and identify the key spots to visit. On Thursday, October 27, at the top of the Eiffel Tower, M. Monlong immortalizes their voyage. The group photo shows, from left to right, the two Jean-Pierres, Guillaume, and Jean-Louis; and seated in the middle, a short, dark-haired girl stares into the lens, Thérèse. Across the top of the snapshot, a pen scrawl in the sky over Paris gives the place and date.

The shepherds cling together inside Orly Airport and reconvene at the back of the airplane, picking up the conversation that has been going nonstop since they left the train station in Bordeaux. At first excited, they grow apprehensive about the flight, then as the plane tucks itself between two clouds, the conversation flows again. Cerdan is just a dozen yards away. They can’t get over it.

Dawns are heartbreaking.

— Arthur Rimbaud, “The Drunken Boat”

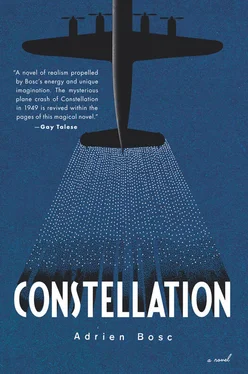

Dawn is breaking over the Azores archipelago. Boats belonging to the Portuguese authorities are still hoping to find traces of the Constellation. Eight airplanes take off from the Santa Maria airfield looking for F-BAZN. They fly over the island, the mountainous ridge of the Serra Verde, the Pico Alto, scrutinize in length and breadth this rock thrust upward by the sole force of a volcano. Santa Maria is an oceanic island, a few thousand herders and fishermen are isolated on this steamboat stalled in the middle of the Atlantic. This morning, Friday, October 28, 1949, the airplanes trace the outlines of a boundary scrawled with the diagonals of contrails. White cross-hatching, like a map of the archipelago.

Several hours elapse, the Constellation remains unfound, vaporized in a triangle of the Azores. Paulo Gomes’s search plane strays from the area targeted by the authorities and explores to the north, farther out, toward the islands of São Miguel and Terceira. A hunch. Halfway between Santa Maria and São Miguel, the pilot sees, rising from Mount Redondo like an Indian signal, a smoke cloud, a coiling scroll of smoke that adds several yards to the mountain. Above its belt of haze, the telegraphic puffs sing:

Scrolls of coiling smoke

Your toils gone

Clouds broken open

Paulo Gomes continues north and flies over Mount Redondo at an altitude of four thousand feet, circling the summit, and discovers the dislocated carcass of the Constellation smoldering on the mountainside. The ripped-off wings and, a few hundred yards below, the remainder of the four-engine plane. A pool in the center burns with the last liters of kerosene from the aircraft. Around the dismembered wading bird are figures in motion, seemingly survivors.

Scrolls of coiling smoke

Drift past the dimmed eyes

Of flashing dragonflies

Hope rises again in the search plane, and the pilot sends the information to the control center. A few minutes later, the authorities on Santa Maria send a telegram to Lisbon: F-BAZN AIRCRAFT FOUND ALGARVIA PEAK LOCATED NORTHWEST SAO MIGUEL STOP PLANE SAYS THERE ARE SURVIVORS STOP GOING CLOSER TO LOOK STOP. The message was intercepted by Air France in Paris during the early afternoon. As boats from the island made their way to São Miguel, the airline sent its own rescue mission by plane.

Scrolls of coiling smoke

Drift in plumes

Читать дальше