Those flights over the Mediterranean were a long time ago, the best years of his life, he often said. The capture of Pantelleria Island on June 10, 1943, then Linosa, Lampedusa, and the celebrated invasion of Sicily. Thirty-eight days of ferrying forces from the advanced base on Pantelleria, twenty-eight men to a Dakota. And leaving in his wake, as he shuttled back and forth, traceries of parachute canopies in the sky. Operation Avalanche against Salerno, and Slapstick to take the port of Taranto. The great battle, Monte Cassino, would come on May 11, 1944. Then parachute drops over Provence. In Casablanca, the Allied rear base, Jean would return to life. History was in the making, and he was part of it, an extra in the great theater of operations organized by Churchill and Roosevelt at the Casablanca Conference. De Gaulle, Giraud, a few demobilized veterans from the French Naval Air Force, and the French Army, which was now the second blade of the Allied operation — all these men, tenacious and battle-hardened, hungered for revenge and reconquest. In the postwar years, he brought his wife to the Max Linder cinema to see Casablanca with Ingrid Bergman and Humphrey Bogart. He took exception to the casbah, so much at variance with his own recollections, and laughed out loud at the singing of the Marseillaise led by the resistance fighter Laszlo. Total joke. Walking back up the boulevard Poissonnière, he described his Casablanca to Aurore. The hotel in the Anfa district and the restaurant with the panoramic view. The palm groves around Camp Cazes airfield and the barracks where the pilots were packed together. The runway, which features as the final set of the film, where Rick Blaine and Captain Renault celebrate the beginning of a beautiful friendship. He also told her about the history of the Moroccan airmail service, about the exploits of Mermoz and Saint-Exupéry, flying over the desert, over sand dunes, where you see nothing, hear nothing, and beauty is hidden in immensity.

On the night of October 27, 1949, Jean de La Noüe, captain aboard F-BAZN, has sixty thousand flight hours and eighty-eight transatlantic crossings to his credit. Next to him are Charles Wolfer and Camille Fidency, two former combat pilots. Since hostilities ended there has been no front to receive these soldiers. Like Jean, they chose not to pursue a career in naval aviation, adapting instead to this new line of commercial work. Assigned to the same flights, the two have become friends. And born the same hour on December 4, 1920, they are known in the company as the “astrological twins.” Soon, between stopovers, they will celebrate their twenty-ninth birthday. The radio is manned by Roger Pierre and Paul Giraud, the navigator is Jean Salvatori. And André Villet and Marcel Sarrazin, mechanics, complete the flight crew.

The airplane! The airplane! May it climb to the sky,

Soar over the peaks, and cross the watery divide.

— Guillaume Apollinaire, “L’Avion” in Poèmes retrouvés (Rediscovered poems)

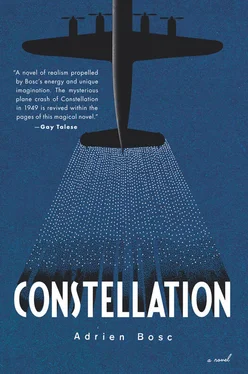

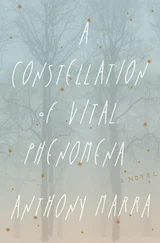

“The new comet from Air France,” read the advertising brochures. The Constellation was going to supplant luxury ocean liners and establish the dominance of air over sea. A chrome-plated bird born of the folly of one man, Howard Hughes.

The majority stockholder of Trans World Airlines, Hughes had launched the project to build the “Connie” in 1939. Working with Lockheed Aircraft, the film and aviation magnate proposed a new gamble: a pressurized four-engine passenger plane capable of traveling 3,500 miles in one hop. He drew the plans freehand, his sketches guided by a taste for elegance and eroticism, leaving to the engineers the task of adapting them to the laws of aeronautics. During that same period, for the shooting of The Outlaw , Hughes designed a cantilevered bra with steel undercup rods that turned Jane Russell’s breasts into missiles aimed at the screen and at the leagues of public decency.

Initially brought into the U.S. Army Air Force program and used for troop transport between continents, the Constellation logged its first commercial flight in 1944 when, with its eccentric billionaire at the controls, it shattered existing records by flying from Burbank, California, to Washington, D.C., in six hours and fifty-seven minutes. On February 15, 1946, the producer-aviator invited a group of Hollywood luminaries on a nonstop flight from New York to Los Angeles. At an altitude of twenty-five thousand feet, flanked by Paulette Goddard and Linda Darnell, and holding a megaphone in one hand and a glass of champagne in the other, Hughes presented his new toy. With the Constellation and its stars, aviation was entering an era of aluminized luxury. But though it was a symbol of the prop-driven transatlantic airliner at its zenith, the Connie’s early flights belied its eventual destiny. Singular law of series. On June 18, 1946, one of the four engines of a Pan Am Constellation caught fire. The pilot managed to remain in the air over the continental United States for eleven hours all the same. The Constellation, which the press dubbed “the best three-engine aircraft in the world,” suffered another accident twenty-three days later when a Connie made an emergency landing in a field, killing five of its six passengers. As a precaution, all Constellations were grounded until Lockheed could effect the necessary changes. Once the adjustments were made, a few months later, the Constellation again received its certificate of airworthiness and established itself as the premier long-range aircraft for transport companies worldwide. Among them was Air France, once privately held but now nationalized, which ordered thirteen planes from Lockheed. The first Air France Constellation, registration number F-BAZA, took off from La Guardia Airport on July 9, 1946, Roger Loubry captain. Starting on October 8, 1947, when Air France inaugurated its “Golden Comet” luxury service, the carrier could boast of being the only airliner to offer sleeping berths on transatlantic routes, reducing the sixteen-hour flight to a long night’s sleep.

Once the French coastline is behind them, the stewardess, Suzanne Roig, and the two stewards, Albert Brucker and Raymond Redon, busy themselves around the cabin. Marcel Cerdan, after a brief courtesy visit to the cockpit, sits next to his friend Paul Genser. In front of them is Jo Longman, in conversation with the journalist René Hauth, editor in chief of an Alsace daily newspaper. The latter is asking about the champion’s physical condition, his regimen, the training camp they have chosen, and any concerns the manager might have, for a dispatch he’ll telegraph to his editors from New York in the morning. A golden opportunity to gather firsthand information in mid-flight. Air travel’s happy coincidences bring about the most improbable encounters. In the back of the plane, Jean and Ginette Neveu talk in undertones and meet their neighbor, Edward Supine, a lace importer from Brooklyn returning from a business trip to Calais. Somewhat embarrassed, he admits to not knowing much about music but promises to listen to one of their recordings and asks the virtuoso to spell her name. Guy Jasmin, four seats back, starts reading Moby-Dick , which he bought the previous day at the Gallimard bookstore on the boulevard Raspail. The opening words are unmistakably engaging: “Je m’appelle Ishmaël. Mettons .” “Call me Ishmael. Some years ago — never mind how long precisely — having little or no money in my purse, and nothing in particular to interest me on the shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world.”

Читать дальше