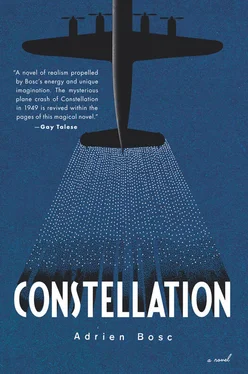

In the Azores, the Day of the Dead, November 1, 1949, has never been more aptly named. Mass is being celebrated continuously on the island in honor of the Constellation’s victims. The locals have begun to feel affection for the passengers, their mourning tinged with pride, the fleeting sense that, for a few days at least, they are at the epicenter of a global tragedy. They learn the names of the dead, Ginette Neveu, Marcel Cerdan, and wear mourning for the crash victims, who by the will of providence have become their own dead. It will take almost a week before the bodies are returned to France. The French consul, Morin, has arrived in São Miguel and now coordinates operations. The thirty-three French coffins wait at the Ponta Delgada barracks while the experts continue their investigations and establish the identity of each victim. On Monday, November 7, in the early afternoon, the grim cargo is loaded onto a vessel plying between São Miguel and Santa Maria, where airborne hearses await it on the landing strip, three LB-30 Liberator cargo planes provided by the International Air Transport Society (SATI). Huge, slab-sided aircraft, built in Detroit’s assembly plants and destined for the British Allies, they fly according to the dictates of the commercial world. Fanned out across the tarmac, the identical triplets, their loading ramps deployed, will swallow — like the whale in Walt Disney’s Pinocchio — the mortal remains of the Paris — New York flight. On Tuesday, November 8, at dawn, cargo aircraft F-00AF takes on board the bodies of the thirty-three French nationals for a two-tier flight: a jink to Casablanca to drop off Cerdan, then a second leg to Cormeilles-en-Vexin, Orly’s annex.

The trade winds at its back, the cargo plane flies over the Strait of Gibraltar, then begins its descent toward Casablanca and the Camp Cazes aerodrome. Is anyone aware that the Constellation’s pilot, Jean de La Noüe, is returning to a land he knows well? A land that Bernard Boutet de Monvel painted? The throng crowding the runways mourns a boxer named after an airplane. At 10:00 a.m. local time, carried down the boarding ramp of a cargo Liberator on four shoulders, comes Cerdan, the Bomber. A continuous double line of grieving fans attends the coffin along the palm-fringed road to Lyautey Stadium. In the sports arena, at the end of the avenue d’Amade, in a hastily built hotbox of a chapel, thousands of Casablancans file past the catafalque where the champion will lie until his burial.

Don’t ever tell anybody anything. If you do, you start missing everybody.

— J. D. Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye

I had read, in a contemporary press cutting, an anecdote about one of the passengers aboard the Constellation. His name was Ernest Lowenstein, the owner of two tanneries, one in Strasbourg, the other in Casablanca. It said he had divorced a month earlier in Reno and was going to New York for the sole purpose of trying to reconcile with his wife. The story struck me, I imagined the telegram sent a week before the plane flew, something like: ARRIVING NEW YORK 28 OCTOBER STOP CONSTELLATION F-BAZN STOP LET’S MEET STOP I MISS YOU STOP. I was fascinated by the history of Reno, Nevada. The city became the divorce capital of the United States at the beginning of the twentieth century and continued in that role until the late 1960s. A federal law had made divorce proceedings easier, no proof of adultery was required, a claim of “incompatibility” or “mental cruelty” was enough to obtain the precious document. Wanting to kill two birds with one stone, the local authorities gradually decreased the residency requirement from six months to six weeks, making Reno a tourist town with a sideline in divorce. I learned that Mary Pickford, the silent film star, came to live there for six months in 1920 to speed her divorce from Owen Moore and fly into the arms of Douglas Fairbanks. There were also tales of the Riverside Hotel, the great stars of Hollywood staying there when they wanted to expedite their breakups, including Paulette Goddard coming in 1935 to end her marriage to Charlie Chaplin. I discovered an American popular song:

I’m on my way to Reno ,

I’m leaving town today

Give my regards to all the boys

And girls along Broadway

Once I get my liberty ,

No more wedding bells for me

Shouting the battle cry of Freedom!

I pushed my research further, hoping to find more information about Ernest Lowenstein. Finally, on November 2, 2013, I came across an article that appeared on October 31, 1949, in the Ironwood Daily Globe , a Michigan newspaper. At the time, I was stupidly enjoying the paper’s name, Daily Globe , it reminded me of the paper for which Peter Parker worked, the photographer-hero of the Spider-Man comics. An article entitled “The Hope That Failed” described the victims’ families, waiting at New York’s Idlewild Airport. It told how the rumor of possible survivors, debunked a few hours later, had encouraged a vain hope and exacerbated the despair of friends and family. The photograph accompanying the article captured the precise moment of that hope. The caption read: “Mrs. Ernest Lowenstein of New York hugs her nine-year-old son, Bobby, having heard from a friend that her ex-husband, Ernest Lowenstein, of New York and Casablanca, survived the Air France crash in the Azores. The rumor shortly proved to be false. There were no survivors. Mrs. Lowenstein said she had obtained a divorce in Reno a month ago, but that her husband was returning to the United States to discuss a reconciliation.” Bobby, nine years old, he should be traceable, Robert Lowenstein, born in 1940, there can’t be tons of them, the child in the photo would be seventy-three now, there’s a good chance he’s still alive. Google turned up three possibilities, one of them a child psychiatrist in Pittsburgh, Robert Aaron Lowenstein. I found his e-mail address on the clinic’s website and wrote him this message:

Date: November 2, 2013, 00:57:54

Topic: Ernest Lowenstein

Dear Doctor Lowenstein,

My name is Adrien Bosc, I am working on the plane crash F-BAZN Constellation.

I’m not sure you’re the son of Ernest Lowenstein, if so may I ask you a few questions?

Best regards,

Adrien Bosc

Two hours later, I received a reply, which I read when I awoke:

I am his son. What questions do you have?

Sent from my iPhone

I’d written on the off chance, and the truth is I didn’t think I’d find him so easily. When I reread my e-mail, I was a little embarrassed. I’d begun my query abruptly and without any real precaution, not considering the strangeness of my topic line, “Ernest Lowenstein,” sixty-four years after what had surely been the major tragedy of his son’s life. There was a vulture side to it, crassly journalistic, in fact.

After several exchanges, we agreed on a telephone conversation on Sunday, November 10. I explained my project to him, told him that I wanted to hear his version and not rely just on the press clippings. Reassured, he told me the story of his parents:

My father, Ernest, was a German Jew, who was born in Westphalia and immigrated to Paris in the late 1930s. He worked for my uncle in the leather business. My mother was Polish and had also immigrated to France. They met in Paris. In 1940, when the Germans arrived, my father was away. He had enlisted in the Foreign Legion and was on a combat mission in Algeria. My mother, then pregnant with me, decided to leave Paris. She managed to cross the Pyrenees into Spain. A French family helped her by giving her a ride in their car. From Spain, she took a boat to Casablanca, where I was born. My father came from Algeria to join us. We spent the entire war in Morocco, with my father working first as a policeman, then starting a tannery. In 1945, we immigrated to the United States. My father’s business took off after the war, and he traveled a great deal between New York, Morocco, and France, where he had started a second processing plant. We spoke French at home, it was my first language. We also spoke German and Polish. Then, in the summer of 1949, my parents divorced. I remember the trip to Reno, which seemed like a vacation. My mother and I lived there for six weeks. I didn’t understand everything that was happening. It was summertime and it just seemed like a holiday. Then there was the Air France flight, they told us he had survived, and then they told us there were no survivors. A few days later, his body was identified. Lots of reporters staked out our house. The story of the reconciliation is true. I knew that was the point of his trip, and that my mother was favorable to the idea. She was a very energetic woman. After my father’s death, she became one of the first female stockbrokers in New York. My mother was very enterprising .

Читать дальше