… I’m so happy to love you the way I do. Only twelve days and I’ll be able to touch you and kiss you as I want .

Your own tiny tiny

In August on the Côte d’Azur, and then on the ocean liner Île de France , he had sworn that he would make a decision after his victory. He would stop his career, have the time to think. Step back before taking a leap. Then the news came, the match was delayed.

Marcel Cerdan, ensconced with his family near Casablanca, was killing time, hanging on LaMotta’s decision. Marinette was there, his three children, his brother Armand, and his nephew René, who had become his sparring partner. He bounced between the farm at Sidi Maârouf, the villa under construction at Ansa, and the ASPTT boxing gym, where he practiced his scales. Batting rhythmically at the leather hide of the speedball. Bif, baf, bif. Harder, left, right, left, punish that punching bag, whumpf, whumpf, whumpf. The jump rope snicks against the wooden floor, whack, whack, whack.

Marcel had trouble accepting the fact that he’d been taken by an outsider who came out of nowhere, out of the pocket of some Cosa Nostra godfather. A bitter-tasting defeat to the world’s tenth-ranked middleweight, a confluence of events that were suspect, to say the least, and had erased any possibility of victory. At Briggs Stadium in Detroit, on June 16, 1949, the bout had been moved forward half an hour. Marcel was unable to complete his ritual warm-up before entering the ring. Cold, he slipped in the first round, dislocating his right shoulder, and was forced to absorb the epileptic flurries of the Bronx Bull. It hadn’t been a washout. LaMotta had battered his tender shoulder until the pain was unbearable. In the eleventh round, pressured by his cornermen, the Frenchman conceded.

He knew that at full capacity he was unbeatable. And the Cerdan flying toward the United States in October 1949 was at the top of his form. “Today, defeat is unthinkable. I have to beat LaMotta, I’m going to beat him. I’ll be perfect on December 2. Believe me, I’ll return to France firmly wearing the world middleweight crown,” he told a journalist from France-Soir .

In the departure hall at Orly, Marcel is wearing his lucky blue suit. Over it, further bulking up his giant frame, is a heavy gray tweed coat. The boxer is superstitious and has his habits, never departing from them in the ring or out. In fact, he blames his defeat in Detroit a few months earlier on the disruption to his ritual. If the conditions for his ritual preparation had been respected, if he had been able to warm up as he’d planned, his shoulder would have been fine, and they wouldn’t be facing a return match today. Instead he’d be defending an inviolate title. Athletes give inordinate importance to these details, which allow them to contain the unpredictable within a series of well-determined causes. If fate can’t be absolutely mastered, then at least let’s ensure the lead-up, encase the details of preparation inside a subjective magic, a prematch paganism. Crazy tics, raised to the level of ceremonial rites, some might say. But adhering rigidly to details is not more odd than using a thousand-year-old liturgy that has hardened into dogma. Ordained a champion, you must never fail in observing the religion you have settled on yourself. Since his first professional fights in Levallois, Marcel has worn the blue trunks with the white stripe that his mother made for him, sewing a medal of the baby Jesus between two tucks. And only by winding the ACE bandages just so can you conjure victory.

Despite his superstition, Marcel Cerdan paid no attention to Arista’s prophecy. The famous fortune-teller met the boxer at Paul Genser’s apartment on the rue d’Orsel in early October. Tickled, Marcel took part in the game. Laying his two big hands on the table, upturned, he exposed the deep creases across his palms. Cartography of a life, traced by furrows in the skin, where the crisscrossing lines of heart, head, fate, and luck reveal, by their branching and interconnection, the ineluctable workings of providence. Pausing at the mound of Saturn below the index finger, symbol of good or bad luck, Arista delivered a lapidary prophecy that echoed like a warning: “You travel too often by airplane, be careful.” Jo Longman, sitting at the back of the room, dispelled the ominous forecast with his laughter and, imitating the fortune-teller’s voice, predicted that Cerdan would soon meet a man-bull, a kind of Minotaur, whom he would knock to the ground, and he added that, Theseus-like, he would emerge from the labyrinth of New York with an Ariadne called Édith on his arm and that the prophecy would come true on his return, when, like Icarus, he would perish from his flight. The augury was buried under general hilarity. The next day, Arista, troubled by his prophecy, asked for and insisted on getting the boxer’s birth record, so as to draw up an accurate horoscope. A week later, Marcel received a letter with a second warning: “Avoid air travel, especially on Fridays.”

The lesson of Cassandra is that the more specifically an oracle speaks, the less she is listened to. And if a prophecy is heard and heeded, every action taken to ward it off helps bring it about. To struggle, to reverse course, is all part of the game, that’s the lesson of the oracle at Delphi. In short, no one escapes his fate.

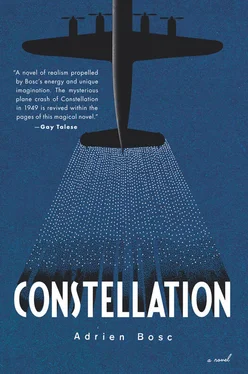

“Take the plane, the boat is too slow!” Édith pleaded over the telephone the day before. The Constellation crossed the Atlantic on Thursday night and arrived in New York the next morning. He could come wake her up, they would spend the day together, and that night he would hear her sing at the Versailles. The prophecy is forgotten. Marinette calls a few minutes before the flight to tell him she has a bad feeling, is anxious. He has never known her to have such fears. He reassures her. Meanwhile, Jo Longman wrests three seats from the Air France receptionists, even though the flight is full. The world champion deserves to take precedence all the same, which he does at the expense of Mme Erdmann, director of a perfume company, and a young American couple who have been honeymooning in Paris. At the airport bar, his sidekicks to the right and left of him, Marcel drinks to his comeback.

“LaMotta has got it coming to him for stealing my title!”

Below the kirk, below the hill,

Below the lighthouse top.

— Samuel Taylor Coleridge, “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”

During the night of Sunday to Monday, a final expedition ascends Mount Redondo in search of the last victims of the Constellation, over which three infantrymen from the local barracks stand guard. At midnight, the rescuers bring the remains back to the village. The hamlet is under siege, the traffic of military vehicles blocks the only street and carves deep ruts in the ground. Housed in the presbytery adjoining the church, the members of the Air France commission gather their notes and draft their first reports. Hundreds of details, which they match with the typed passenger list. Their first priority is to attach a name to each corpse before it is transferred to Ponta Delgada. The technical report on the accident’s causes can wait. What do they feel, these men at the forefront of the disaster? Discouragement at the sheer size of the job? Weariness from a day at the center of the volcano, grubbing through and analyzing the smoldering entrails of the Constellation? Anger that the site was looted?

Читать дальше