COMODOR

NAERATIVS

CE REALISVC

CONS ORD

CONDITOR

BALNEARVM

CENSVIT

Comodor was the son of Marcus Aurelius. He didn’t want to be a philosopher like his father, it was his wish to be a gladiator. To hack with the axe and to chop with the broadsword. All the statues of the city have mutilated faces. Somewhere an ancient Hungarian wanders through the streets with two plastic bags filled with chopped-off noses. Sometimes he goes to hide from the sun in another green reverie where there are marble slabs set in the soil and the nosy shadow of a pyramid. He considers it his duty to bring modest bites of food for the dead. But he can’t stand birds. He tries to give them the evil eyes. He believes them to be the uncontrolled thoughts of the deceased. He throws marble noses at them, trying to kill them. What is the sense of death if thoughts can continue?

In Ka’afir’s book there is the description of the life of a masterful sculptor. The apotheosis of his work was to be his own grave. It was of imposing dimensions as he was seven feet tall. For many years he carved and moulded — fashioning the friezes, twining the limbs, sculpting the horses, situating the snakes. It was to embody the eternity of life bearing the kernel of death. He often used to snigger up his sleeve and because he had a long nose his nickname was Horse. He completed the tomb, died, was laid away, the earth grew over it as if to heal a scar, nobody remembers its position. Death is on the side of awakening. It lies on its side next to awakening. It is awakening’s love-partner. When they make love, horses pull back their lips, flare their nostrils and paw the air; all time is effaced.

Dead birds litter the streets. Ants, small and black like words, are busy deconstructing the bodies mouthful by mouthful, remembering through dismemberment. In Ka’afir’s book there is the numbering of the thoughts of a man. Impressions and images litter the ancient capital of the man’s mind. He never wanted to be a thinker, he didn’t want to have a long nose. It was his wish to be happy, like a radio playing all to itself on the beach. The spy and the actor are after all in the same line of work, they occupy similar fields of entertainment, they paint the birds white. On balconies old women are sunning their varicose veins, old men are picking dead leaves from pot plants. The sun is so bright it must be refracting all available light. Young women arch their backs: they wear wee panties with just a touch of fur sown to the cleft, or a live butterfly. It will be good to sit on the roof, to follow the sun’s labours by nose, to think or to dream of T’ai chi , of slow tongue-gestures, of beheaded statesmen in the grip of stone, of marble slabs in grass greened by a pyramid’s shade, of killing birds as food for the dead gods, of the earth munching the light and integrating all dreams, of mirrors and of Horse. Consciousness drags thoughts behind it, as the jumper his billowing parachute along the ground. One must jump.

Then there is also the description of the man and his image. The man has a mirror in which he tries to locate and capture the sun. It is the Other. The mirror is black, but as the man leans forward to think he imagines seeing in its depths the mythical beast always at the back of his mind. The white horse. He emits a shuddering sigh. ‘He whose horse is the first to whinny at dawn will be king.’ Those who come to visit death first of all see the head of the horse. I don’t need a master, the man says. Does one have to have one to go for a shit? The man says: I shall write you down and I shall give it the title of All One Horse . You are black. You could be my brother. When the sun goes down the man shoots the mirror. There is a shuddering sigh. One must jump.

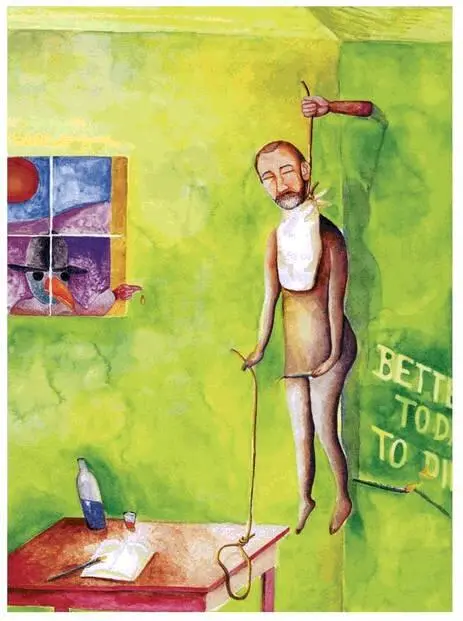

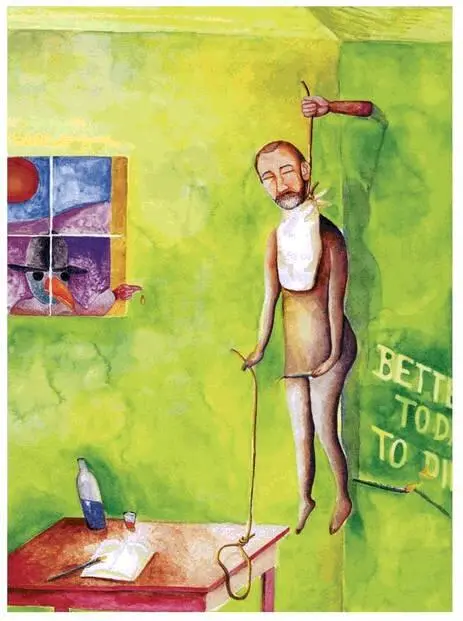

Then, in the seventh paragraph, there is the man. Name : Wormfood, though some know him as Bird-dream. Appearance : Hair like wool which has gathered dust. One cheek curving carved from the sun. Dried blood from one ear. The weal on the neck still fresh, angry, red. Lips drawn back so that the blue tongue protrudes. Eyelids half closed but eyes are looking at the back of the mind. Throat swollen with silence, stuck in the gullet a raucous word as purple as congealed blood. Soiled collar. Cheap jacket. Nothing in the pockets except an ear of paper with the words: I am your brother . Pants, a frayed hem. Underpants stained by ejaculated seed, traces of excretion. No socks. One shoe missing. Body smooth, shoulders drooped, belly slumped, sphincter relaxed, veins on hands swollen, feet loose at ankles, toes with corns, some dirt between toes, about seventeen inches between black toes and floor. Purpose : truth. Truth : no longer.

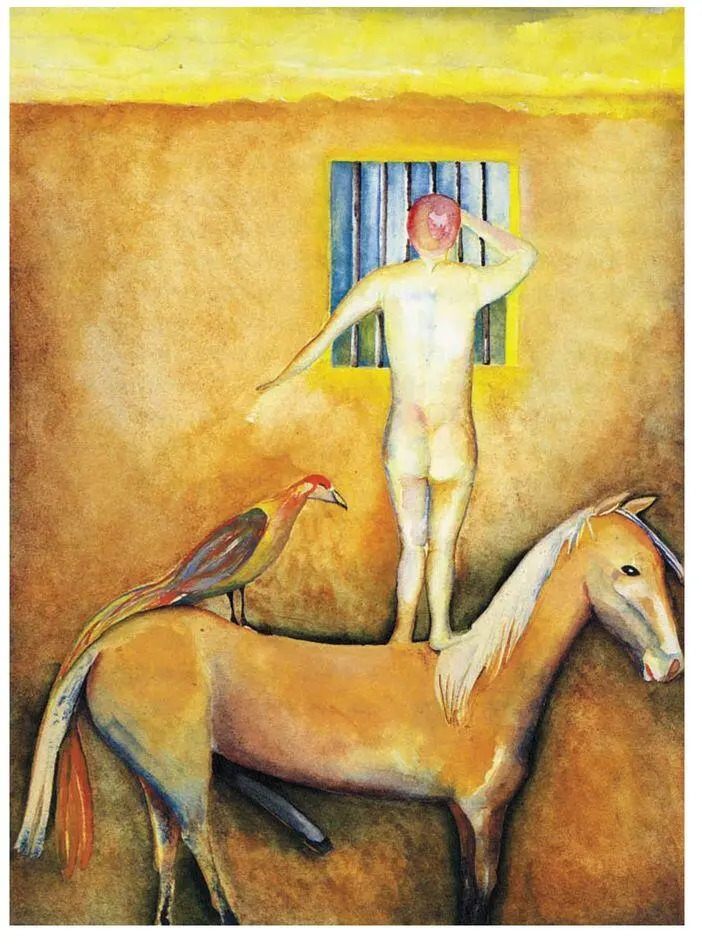

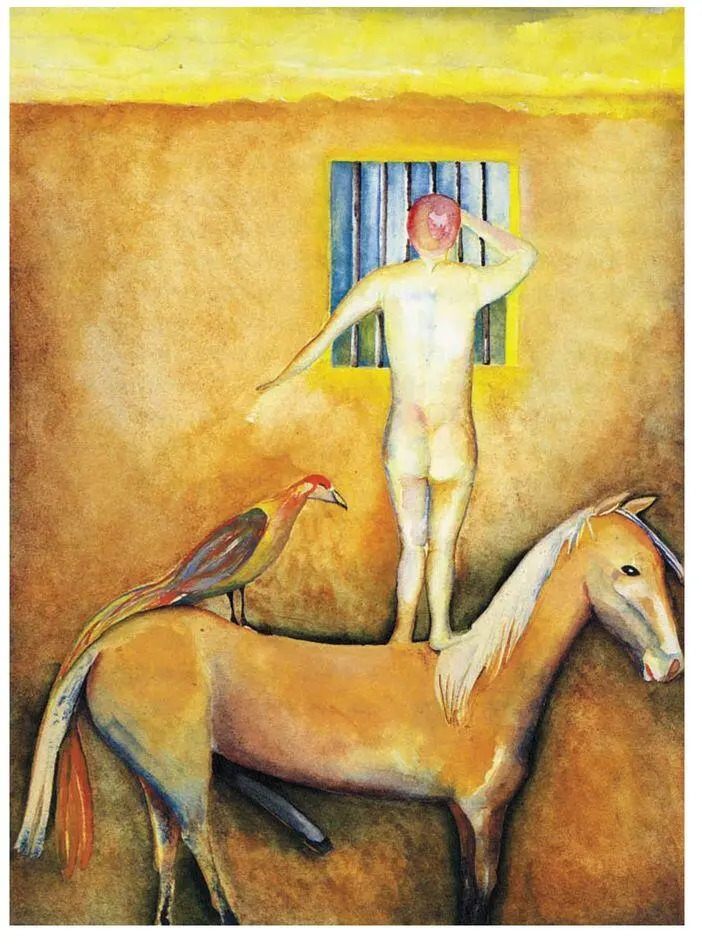

When you are all in prison, the walls are thick, the windows barred, it is too late now. Strange animals may be howling at night. When you are all dressed in tuxedos very smartly, it is essential to keep up appearances. Drinks are doing the rounds, bottoms up and mud in your eye, ‘For he’s a jolly good fe-hello and so say all of us!’ The walls of the cell are of an autochthonous yellow colour, plaster is flaking off, detainees have over the many years been urinating in the corners when they couldn’t hold it any longer and banging against the door brought no attention. Traces of saltpetre, of animal fear. You may be in a stable and you cannot see far enough. Far away the sea is eating the land. Along the blind wall of the prison Jean Genet lies buried in a clifftop koimeterion where the restlessness of the waves gather regularly to impart to the dead the illusion of hearing, but tides will undermine the rockface and his bones will end up in the wash of the waters, like a perfectly pigeoned word never to be pronounced.

I know the story. At the time of the revolt of the Buddhas in Urbos, when they ran through the streets like flames in their saffron robes, when the land was set on fire and later when the floods came because the dykes had been breached and the hedges burnt down, and when all the olive trees had been removed from the face of the earth — after that time, I also went looking for my grave. I came to the island where my father had lived his life and found that the grave had been effaced. I went to the prison where Charley, the caretaker, helped me consult the records. We found the corresponding number, signed and countersigned. Then he took me to the cell. The sea had been there well before us. He showed me the corpse with its caking of white mud, stuffed into a plastic bag together with another, older cadaver. ‘We are economizing space,’ Charley explained.

You may even be free to circulate within the blue-printed confines of the penitentiary. You can don your tuxedo and walk to the courtyard. If possible, if you have the time to do so, if the reaction provoked by fear is not too instantaneous — the freezing of the spine and the finger tightening around the trigger — if you could take a step backwards (let your face be eaten by shadows): you may realize that there’s no need to kill the animal. Admittedly the ‘foreignness’ of the beast is hard to stomach. You may have to clench your mind so as not to slide into a dark snarl, losing all control, that is, the observation of self. Keep the distances alive!

It is hunched against a distant wall of the courtyard, its back turned to you, its haunches big and awkward. Give it a chance. It will turn its big yellow head and the welling up of liquid in its eyes will make you think twice. Give it a free rein, give it time to learn the slow words. When the time is due it will have mastered the words of the script. It will become a better than average actor. Let it play the role of the valet in ‘The Blacks’.

Читать дальше