I wish to introduce you to my twin brother. If I haven’t spoken of him any earlier it is only because he has been until now quite content to live in my shadow. He doesn’t eat very much. Now that he is to appear in broad daylight, I should like to give him a helping hand. Perhaps I should say ‘re-emerge’ like a shadow from the night, because this brother in fact set foot in Urbos long before me and he still has here a network of friends unknown to me. Since that time immemorial, it is true, I had eclipsed him. And as this is a feudal state where success is a story of pulling strings and drawing straws, that is to say of having an obsequious spine and a ready dirk, I ought at least to try and light him on his way.

When we were born my parents were right short on originality which is why they named him simply Brother .

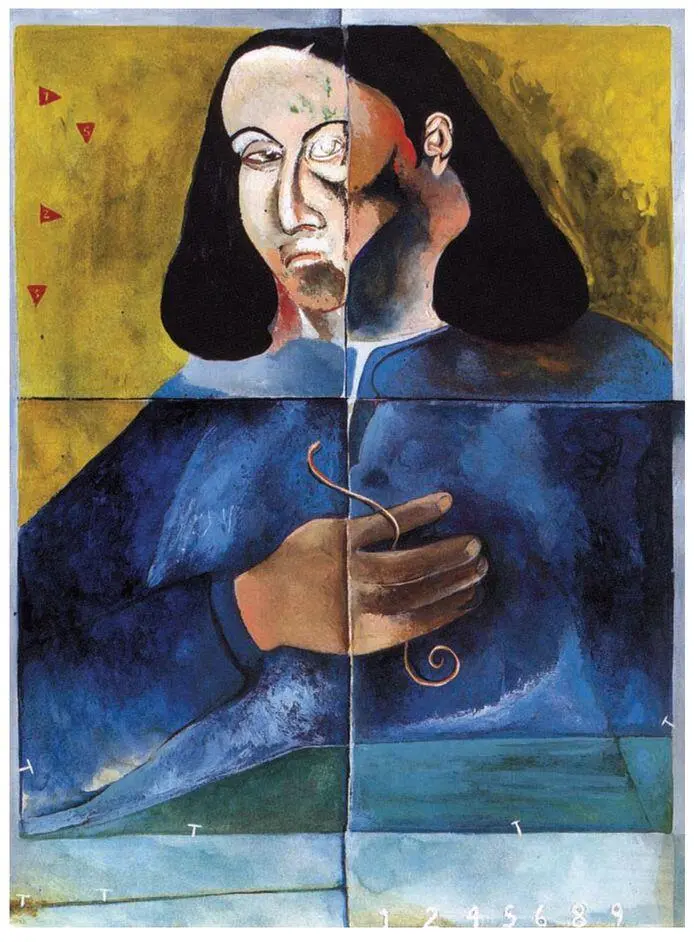

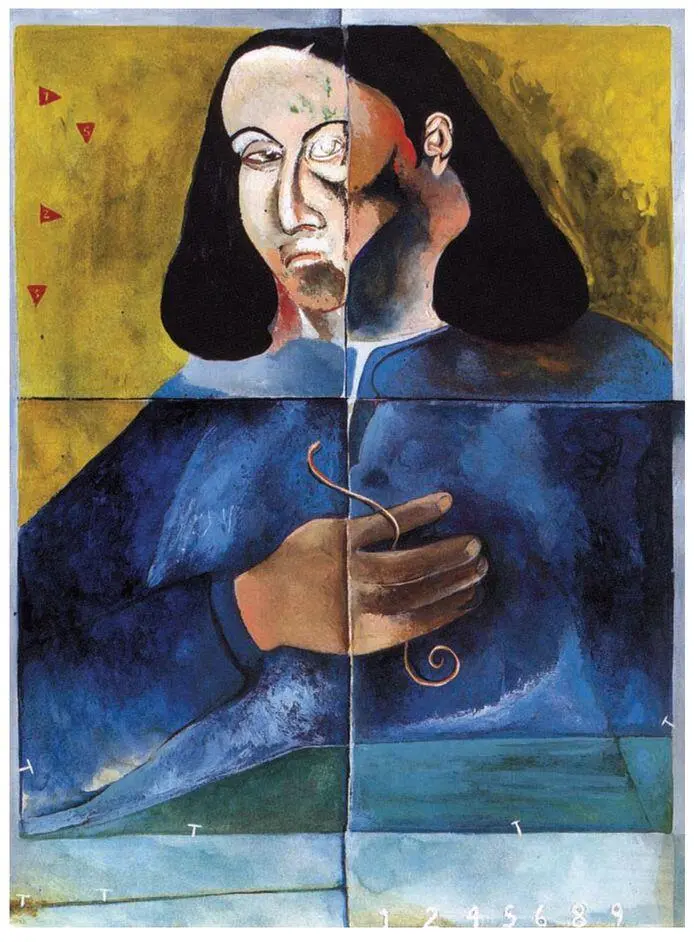

Physically he is my spitting image. To the extent that when he does a self portrait I often wonder whether he’s not trying to picture me. (I forgot to specify that he’s a painter.)

Let me tell you about his favourite painting. It is the Mona Lisa , or La Gioconda as some people think they know it.

‘Why do you like that one best?’ I ask.

‘Because it is a self portrait,’ he answers. ‘More precisely; because it is a painting of myself. I mean it. You smile? Look at my smile and then try to remember. Isn’t it exactly the same? And the trees and rocks in the background, the dead fish light all over — are they not elements of my mind? Some people claim that the thing was done by Leonardo painting himself without a beard. Bullshit! Did you see him do it? And anyway, Leonardo is a figment of the communal imagination. When I die I shall leave my portrait to the king. Of course one can no longer see the painting as it has become invisible. Too many people with framed expectations have looked at it. When a thing is looked at too often it loses its reality. Too many eyes kill the light and fade the pigment. But that suits me fine. In this way it has become a mirror. The original black mirror. Bring it to your face! Can’t you see the self portrait?’

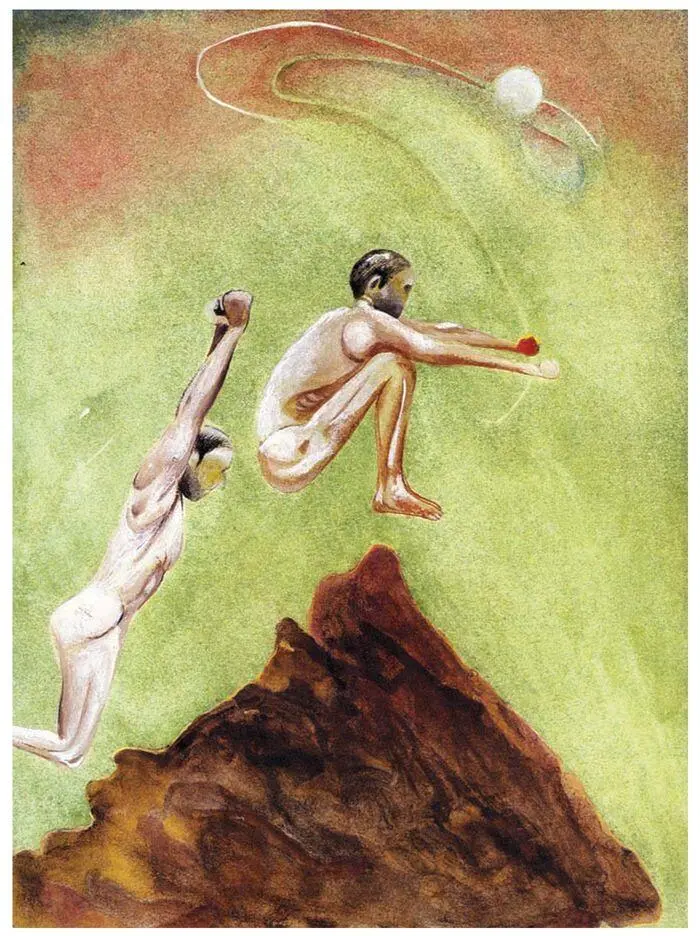

We have been around the world together. We share and share alike the same experiences, or so very nearly so that you may be fooled, but you will never believe it since we have reacted in such totally different ways. Perhaps it is due to his being so much younger than I. Or is it a matter of language? Each tongue is its own boat looking for its own sea. Sometimes it sinks under the dead weight of memories.

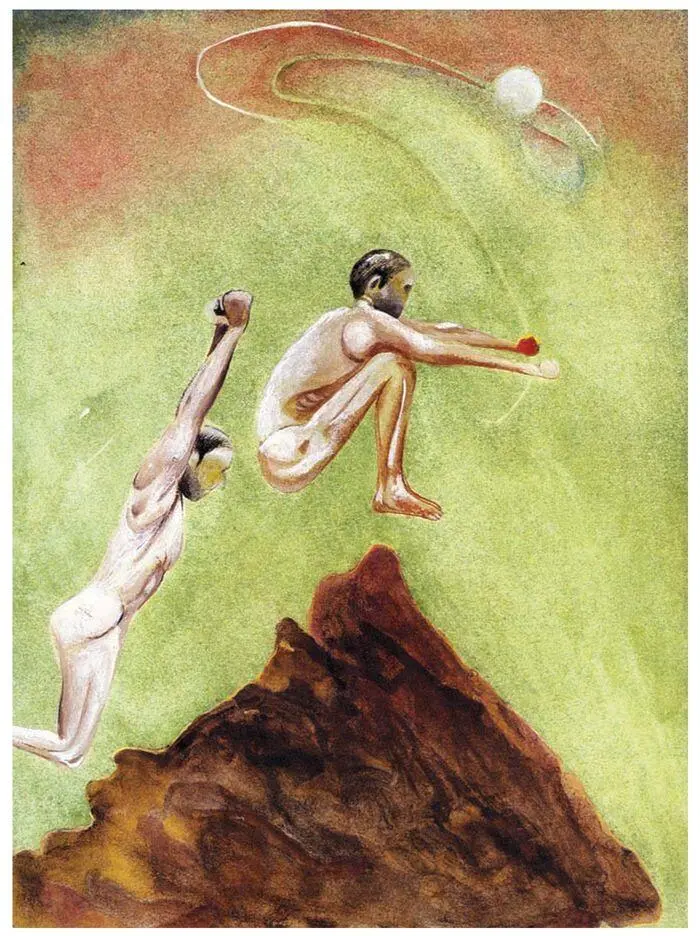

I find him a little primitive still. Primary, you may say. He is a hunter of images. I never know what he thinks and it is hard for me to pinpoint his Africanness. I do know that he is dying to die in a tree like an unfolding of blossoms, that he loves the deserted streets of night and the dead fish light of this town. My wife quite likes him. He may not be the most handsome man or woman on earth, but at least he’s not intelligent. He in turn probably considers me already too smoothed by the life of a Shiny Face in the distant land where you have to explain yourself to be understood, where it is fashionable to be à la mode, where images must be codifiable and digestible. He doesn’t eat very much.

I sincerely doubt if my displaced brother will succeed in being inserted among you, or that he will enter your mind, but I shall nevertheless try and give him his chance. With these words of presentation. And this mirror.

They lived on an estate as big as a park, once upon a time long ago it might have been some sort of citadel beyond the city enclosure, but it is many a memory since it became an integral part of the agglomeration, netted by streets, alleyways, small squares, the hubbub and the teeming of traffic. The park had nevertheless remained a stretch of pristine nature — even if planned, laid out and cultivated — in the midst of the grey city. There nested an old manor house built on a gentle incline with luxuriant gardens all around it. The building itself with its courtyards and the grounds bordering on it was divided in two. One half belonged to them and it was indeed in a dilapidated state but they had started restoring it, creating new spaces as they went along — dining halls, salons, pool rooms, bedrooms. The builders, the plumbers, the electricians were diligently at work and under the grey accumulation and decay brought about by generations of neglect the virile lines of a new deal could already be decried clearly. To gain access to their part of the house you had to pull at a rope outside the gate; it was attached to a bell cast in the shape of a female head which swung comically to and fro and there was the tinny sound of clapper against metal when you jerked the bell-rope. You would hear something, but not know the rights of it. The female bell was mounted on the protection wall just outside the dining-room window. Levedi’s brother had to oversee the alterations; he’d taken up lodgings in a smallish bathroom from where he could direct the activities and the white sheets of his unmade bed hard by the bath were still warm.

The other half had as inhabitant the retired curator of one of the city’s most prestigious art museums. He was a flabby old fellow with an international reputation, tender hands perfectly matching his white cuffs, and two thick wings of snow-white hair sticking out above the ears. His portion of the mansion and the terrain was beautifully manicured, ancient and rampant and soaked in tradition and care, but then he had helpers enough to keep it all in check. His garden was a labyrinth of glistening green lanes, an entanglement for the sun, the foliage in places twice as high as the crown of a man. A couple of ex-prisoners looked after the property — tried clearing the bosky corridor, polished the leaves to a shine, and they puffed at long hand-rolled cigarettes as they walked with a swivelling of the hips while muttering away in an argot which only God could understand. You also heard birds winging by very closely though you would never catch sight of them. The house was stuffed with antiques which the occupant himself would comment upon, and it might be that visitors discreetly paid an admittance fee to come and gape at all the riches, thus perhaps helping to defray the expenses of keeping up the maze.

From the very top floor a view could be had over the city. It was like a décor, layer upon layer, when the sun touched it with the dramatic goldtinted finger of death: chunky constructions with reflecting domes, smoking hills, slim dark red towers — all far off and suggesting perspective but with neither depth nor dimension — and, interspersed with the above, the grey and darkening scurry, the zones of uniformity. One of the narrow passages running along the shadows of a cathedral, an enormous cloister and the blind walls of other strongholds, could be followed by eye for quite some distance from up here. On Sundays few people trod the paving stones: now and then a person in a black robe lugging a rope-bag heavy with groceries and vegetables from the market, and that street had its own wind. Not very far from the estate one could see, looking down, a walled-in square which used to be frequented by Africans only, and then just over the week-ends. Some enterprising money-maker had horses and camels brought there. True, the mounts had shed their hair and the hipjoints jutted out and they were so tame that they must have been as deaf as stones, but the Africans from Mali and Togo and Cameroon and Chad and Mauritania closed their eyes to the alienation and the decadence and clambered on the backs of the docile animals to be thus transported to the larger, desert-deeper spaces of memory and nostalgia. There were swords also, with which you could gird yourself for a brief span, and those too poor to afford a riding-animal could still hire a weapon to handle, to fondle the grip and let the red blade slide from its sheath. Is there life before death? These people did not speak to one another; the dark bodies in the voluminous garbs were silent, under the caps with the sprinkling of sparkling beads the heads were bowed as each communicated with his own absence of mind. The emaciated animals too were immobile, carved from the light, the flared nostrils turned in the direction of a wished-for wind.

Читать дальше