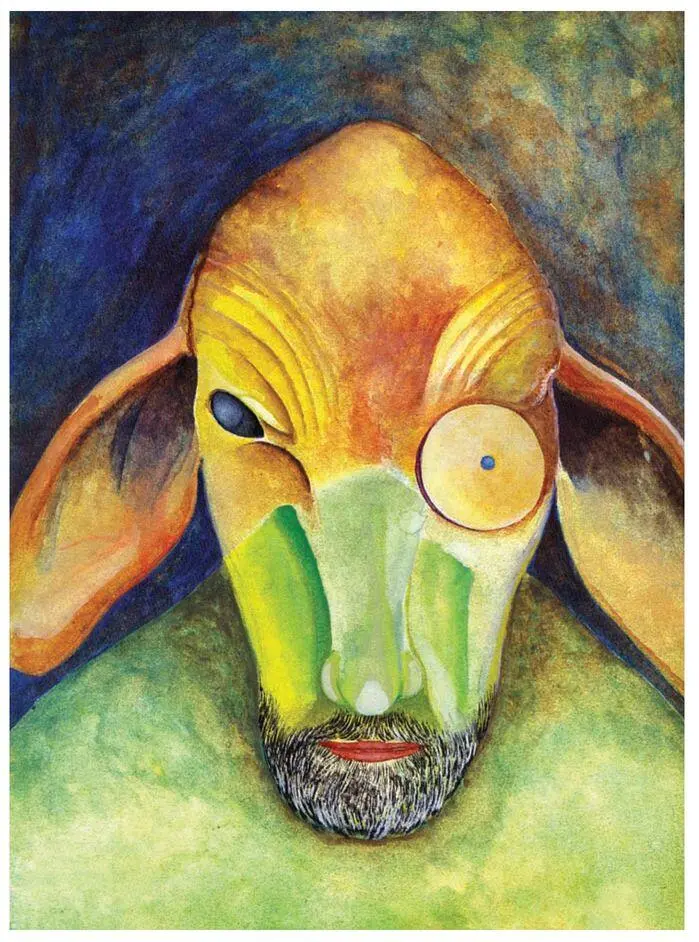

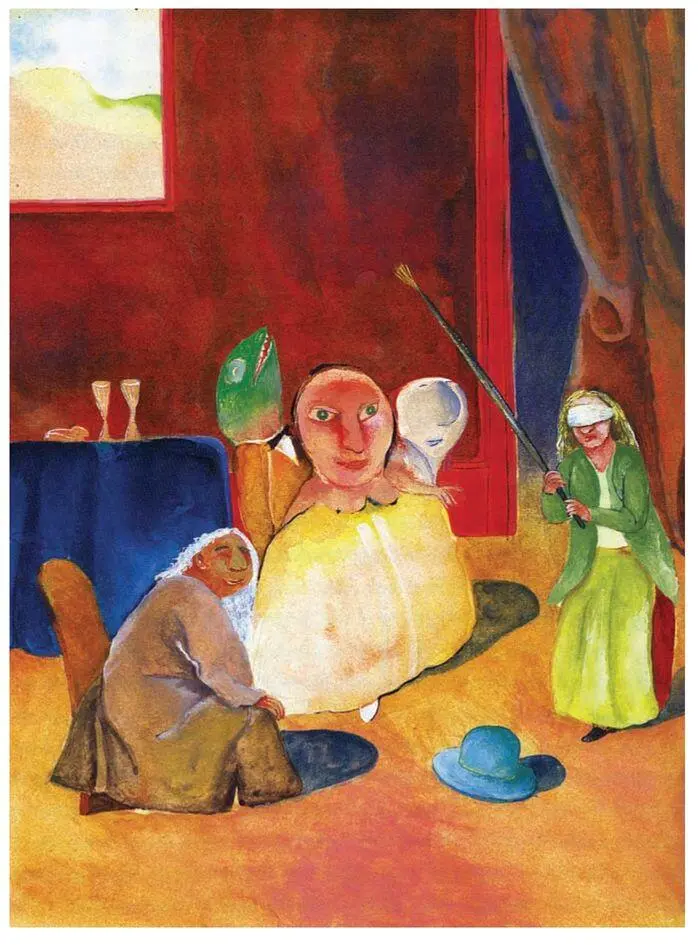

Sometimes when the chlorophyll shrubs flickered during a week-end with wind, and the gurgling of effluent water in the long street of shades imitated birdsong, and the beasts in the square without moving desultorily sniffed for dust, Levedi and Juan also went to visit their neighbour, the old curator, to be informed about the treasures of his house and of the clever ways in which to add to these. Then there was nothing macabre, no apostasy, the air was fresh, the city deployed in its eternal crépuscule, the future very beautiful and very close. The host smiled three or four times and caressed his wrists with sensitive fingertips as if to ascertain that neither fringe nor fimbria dangled from the pale flesh. He would then escort them through the halls over the mirror-floors and always end with the guided tour in the smallest room of all perched practically over the African square. The space — in fact it was a bathroom — they never entered, they just looked in from the outside. On the unmade bed next to the bath, among the warm sheets and as though protected by two pillows, lay the loveliest female head you ever could expect to behold, carved from a nearly transparent rosehued jade or alabaster.

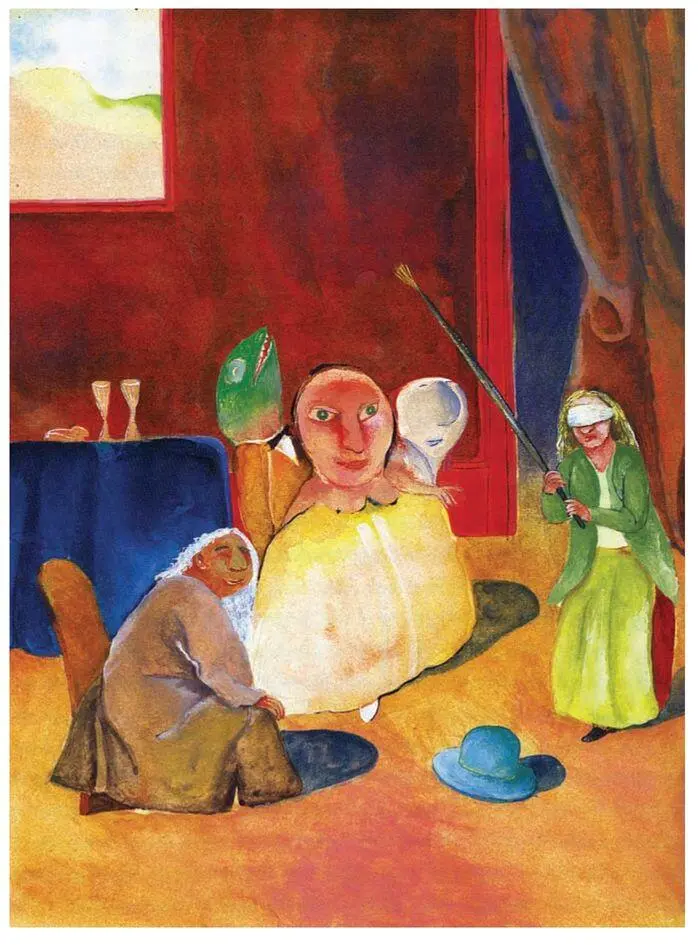

We sailed for long distances in boats on subterranean rivers. We leaned over the deck-railings and saw the corpses drifting by, their loose white clothing nearly filling the baskets. We saw the baskets languidly bobbing in the stream and how some of them became enmeshed in the bulrushes along the banks. Through funnels we hoisted ourselves upward to the light of day. In enormous buildings whose function has become greyed over with time we queued up for food and the dishes were handed out to us through hatches set low in the doors so that we had to go down on our haunches to receive our rations. We stood on a balcony high above the street and watched the procession coming by, sluggish, gloomy, the sluggish and gloomy black banners, and when the shuffling crowd started clapping hands heavily and rhythmically we lifted the arms with open palms to the sky in a solemn salute. Now we are sitting in the narrow room draped in black crêpe. The plates with the greasy grey rests of food were next to our shoes on the carpet. No sunlight illuminated the carpet. Through the french doors giving onto the balcony an oblong strip of blue heaven could be seen. And sometimes clouds like the reflection of the shadows in the street. The bald-headed man rose without letting go of a single word and walked to the lady in the grey dress. His own wife, the spouse of the bald-headed man, looked up from the litter of fingers in her lap and followed her husband’s movements expressionlessly. She never once lowered her gaze. Before the armchair of the lady in grey the bald husband stopped, stooped, propped his hands on the armrests, came even closer, and started rubbing his slightly damp bald dome in a soft caress against the chin, the nose and the forehead of the lady dressed in grey. Without a word. But we could hear the silence growing. After a while the lady pushed him away gently (they had never been introduced, after all) and got up. She preceded him through a slide door to an adjoining room entirely ensconced in twilight — not even the relief of dissipating cloud-floats could bring a glimmer of light this far. The man with the bald head, the pinstriped trousers and the outmoded black jacket followed her without letting slip a word. They did not close the door. The man’s wife remained in her chair, the soiled plate with the crumpled napkin traced with lipstick by her feet, and she continued staring at the spot where the grey lady had been seated just a short moment ago. Only the pale hands in the lap started tightening jerkily as if spasmed by some sort of ecstasy. We experienced the prickly presence of perspiration between shirt and skin. From the neighbouring room the sounds emanated. First the rustling of material being stroked. Thereupon a gasp, or a sigh, or the slow suck of teeth being bared. And then the murmurous monologue of the lady in the grey dress. Was she still wearing her grey dress? We couldn’t see anything. Not what we wanted to. Our eyes were averted to the carpet which was too dark ever again to capture the sun. The wife of the man with the damp baldness softly started to sing-talk. We sat there thinking about our thoughts, listening to the contrapuntal voices of the two women. (The man uttered not a sound.) The streets were once again deserted. People had left for the underground harbours to exchange their black banners for white clothing, to be divided in groups of observers and corpses.

— Yes, said the voice of the lady in the room, softly. What? What? But my lord, you may not… Oh…What are you doing there now… I don’t know you. Don’t you think it will be better if we… Oh… Oh… It will be too… Don’t, please don’t… You, oh, you’ll make that I… Oh, it’s, it’s so… It’s so… Here, a little lower. What are we doing? My lord, but it’s unheard of! Are you taking me for a.. I am, oh I am!… Can it be?… So… More! Again! Don’t… Do! Do! Now! Now! Go! Now! Go! Now! No-oh-ohaah…

— No, the woman in her chair muttered quietly. Can it be?… It is so… Oh… Oh… There?… But I don’t know you… My lord, but it’s unheard of! You will make that I… You, oh you… Are you taking me for.. What? What? Don’t… Oh, what are you doing there now… So?… So… It will be too… Don’t, please don’t… I am, oh I am!… You are!… Don’t you think it will be better if we… Oh, but my lord, you may not… What are we doing?. . Now? What? What? Oh, it’s so… It’s such… There, a little lower. So… Again! More!… Oh… Do! Do! Now! Now! Go! Now! Go! Now! Ye-ah-ah-ee…

the essence of his teaching

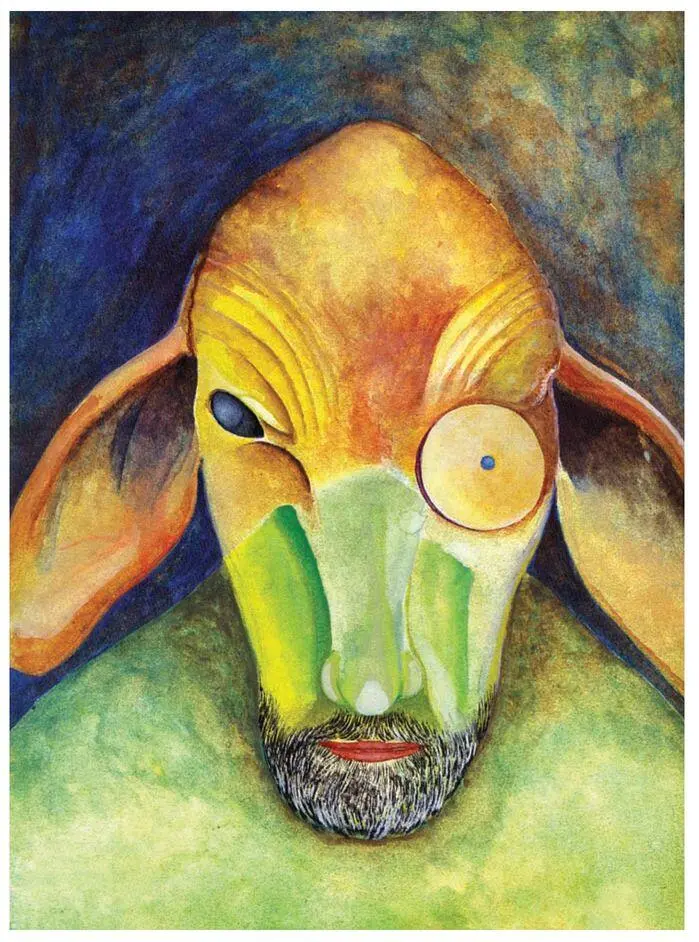

We all know Nascimento Watsenaam, the man who doesn’t dare laugh in public. For reasons of correct behaviour, no doubt, or decorum, or selfesteem, or having to satisfy the tax inspector. He holds it back, he keeps it bottled up until the darkest movement of the night. Then he betakes himself to a secluded spot where he can place both hands on the knees, pull his back in a knot, and vomit up the hot laugh like a jet of undigested mirth. Tears are squeezed through tightly closed eyelids, his facial muscles hurt, his earthly body heaves and shakes. He travels all over the world — from Spain to Rome to Lusaka to Canberra to Bombay. Everywhere the man has to go looking for dark alleys or uncultivated fields or the secret places in the lee of buildings — away from the geometry of the moon — where the penumbra is turgid. We hear him. People are broken from their sleep with shudders and with shivers. Hands fumble for eyeglasses, false teeth, pistols and alarm clocks. ‘What? What was that? Ooohhh…’

On his way from Nomansland to Wet Country, Nascimento Watsenaam stops over in Australia. He goes for a run along very high cliffs, down a brown cracked-mirror path, where only very rich people who can afford to lose a child come jogging in the dew. He is looking for the solitude of unconstrained laughter. He so much wants to see his gurgles writhing on the spear of the sun. The cliff-face is red. He sees carved there in even a deeper red: Now whitefellow has made of the Dreamtime a nightmare . Night can not be trusted. It is too distant.

Читать дальше