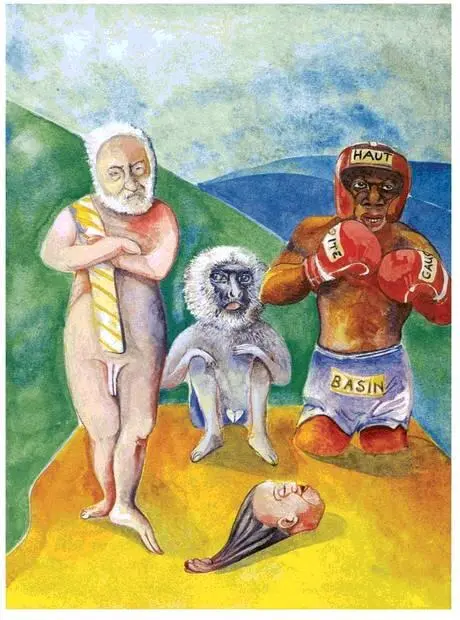

It is like going back to the concavities of my youth. How could I ever have forgotten? I must have grown up here. Here on the corner, surely, here our old house stood. I remember that it used to be filled with the groaning of the sea wafted up the heights at night by the wind. From the windows we would watch the birds — as big as humans with useless shoulders. Imagine picking your nose when you have only wings for arms. There was a big tree then, full of these many-coloured birds. And sometimes a hunter came by early in the morning: he would harpoon one of the huge ones, the others would squawk and flap their heavy feathers, the harpoon was attached to a long nylon line, the hunter could never dislodge the big bird, he would pull and pull trying to reel in his catch, and eventually the entire tree with its colony of violently vituperating birds would budge, shudder, start moving; the hunter would heave and ho the tree as far as the market square down there, then he would stand a ladder against the trunk, we a gaggle of kids would be clustered around, ‘watch out for falling birds,’ he would jest as he climbed up the rungs to knock down his quarry. We then thought that each bird wore a differently patched coat. And here too under the windows we watched the procession of musicians snaking down the street the morning after the revolution. There were not enough instruments to go around so that most of the participants — so young and so vulnerable but so enthusiastic in their patched clothes — carried candles only. Candles make soft noises. In the dawn of the new day we could barely discern the flames of the candles. Each troop had at its head an old exiled agitator or a tired greyhaired gladiator playing a violin or blowing down a dented saxophone. They wore extravagant ties. Ours was a revolution marked by poverty.

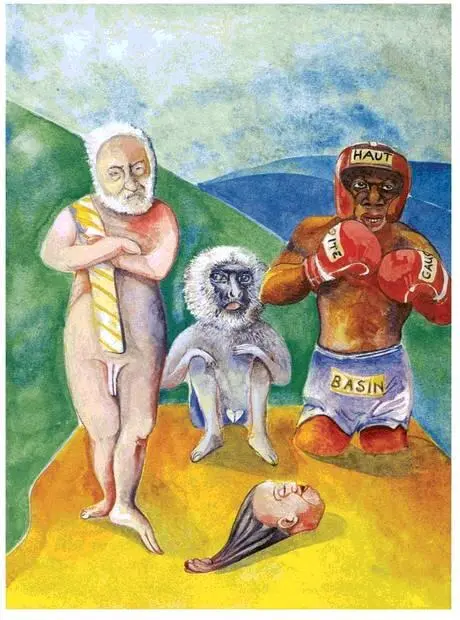

And there is That Place among the dying and the mentally destroyed and the basket cases drooling at the mouth and the vagabonds with their amputated legs and the debilitated jobless ones who have used up all their rights — there we find B. His hair is white. His eyes are still blue. His cheeks are slack. He sits on the ground studying a block of black ebony wood. From the minute grains, the discoloured patches and the whorls, he can read the past and predict the future. It is all written down. What has been will be again and so on forever. He is living below a given horizon. He keeps his eyes lowered. No, he does not recognize us, but at the level of his gaze he remembers very well. ‘I like your tie,’ he mumbles; ‘it is still the same.’ And: ‘When you listen to the shell you can hear the moon moaning.’ I kiss his hands. There is nothing to be done.

We go back to the building of glass coops. I have a life waiting for me, my mother must catch her plane. Charley is waiting for us on the top floor. He smoothes down his tie. ‘I know, know it all,’ he says. ‘Don’t forget that I’m the caretaker. Your brother used to work for us, the police. He was an extraordinary physionomist. Yes, we would let him look at the photos of the suspects and he would read and interpret the profiles for us. Nothing escaped his mind. Maybe that is the reason. Maybe there is a threshold of saturation. A point of no return.’

My mother clutches her cardboard box with gnarled birdlike hands. I return to the glass room of the thin man. The blood has dried on the dark wood. No moon will shine or slime in the liquid. I adjust his hat, bandage his mutilated hands. I bend down low to kiss the wounds and say: ‘You are my brother, you are my brother.’

We leave. We go to the airport. There is an old wind in the empty trees. The flight is announced. ‘Oohh…’ my mother moans. ‘Bebebebe… Don’t leave me…’ But she doesn’t recognize me. Her old black face is bathed in tears.

She washes up in her dinghy on the shore, she has no oars, she clings to the sides of the boat, the sea is insurrectional like a Japanese woodblock print depicting the engulfment of coastline and small human figures, waves sough and smooch on the shale of the beach, sprays give the air a glisten and a sparkle. Flotsam and jetsam. The dowdy dress clings to her shapeless body, grey locks plastered to her forehead, her eyes lie low and sullen in their sodden coffins. She gets out of the dinghy, the dinghy is rolled over by the crashing rollers and smashed to smithereens and rolling planks in the sud and the suck. Unsteady, difficult to keep the footing, slithering through loose pebbles smacked at by the foam-laced water. She goes to hide in the darkest retreat under the jetty, puts her back to a mouldy wooden pillar, turns upon her tormentor, now she is cornered, a snarl on the lips, she is brandishing a pistol. ‘I’ll kill him, I’ll kill him!’ she screeches above the slough and the slosh, the boom of the breakers, spittle flecking her chin. ‘If he comes near me I’ll shoot him like a dog. Imagine, good people, imagine. Why is he after me? Hew says I murdered his wife. Imagine! Why would I do so? I know them from nowhere, never saw them in all my life. Me shoot his whaif? Why ever? She’s exactly my age, I hear. I hear she has the same eyes. I hear without listening. What was there to gain? I’ll kill him, I’ll kill him!’

‘Indeed,’ an onlooker murmurs. ‘I knew the couple. Man and wife. This one here is the spitting image. Same dress. It is passing strange.’

‘Ah, yes,’ the second onlooker sighs. ‘I witnessed the shoot-out this morning. On the other side of the island. On the terrace of the hotel. A man came storming out screaming streams of curses at the mouth. Of his wife having been killed by his jealous mistress. People were knifing their breakfasts. The man was shooting at the air and the earth. People shouted hey hey there ! This woman shouted and shot back. Six people died with red flowers in their hair. She ran off screaming to the marina where the boats are kept like mistresses. I saw it with my own eyes.’

‘Indeed,’ a third onlooker murmurs. ‘Ah, yes,’ a fourth one sighs. What makes you think there ever was another woman?

Ka’afir, the brother, the Other, wrote a work called The First Book Of Slow Gestures . (Some refer to is as The Papers Of Guilt .) It is recommended there that one should cut up in small morsels this entity known as Life. If not, how is one going to digest it? And unless one digests it entirely, how is one ever going to die? These are the ordinary thoughts grazing through the mind of an ordinary guy. The state of death is probably very gentle: a rusting car with wheels gone, resting in a dislocated garden. All things are reduced to the skull of a horse. It is also said that in this garden was found the skeleton of the tallest dwarf ever unearthed. Seven feet tall. The earth is rich.

At the outset of this second paragraph there is indeed a garden. Around the garden there is a city which on certain nights of the month will bear a moon like a Solanum sodomaeum. The city has streets with apartment buildings and insurance offices, also other gardens and then hills with winding gravel paths, umbrella pines, oleander bushes in bloom. Brides go there to be photographed in their white veils. Where the hill falls away, overlooking other gardens, a marble statue stands, dreaming death. Around the shoulders it wears the remnants of a cloak. Its nose is missing. On the pedestal is carved:

Читать дальше