‘It’s best if you get in back,’ said the woman.

I turned to her colleague: ‘Do you know what happened?’

‘Sir, as far as we know your son was hit by a car at approximately four-thirty this morning on the Stadhouderskade. Somewhere near Max Euweplein. We’ve been told he’s in the Intensive Care unit at the AMC. They’re operating on him at the moment. That’s all we know. The driver of the car is being questioned at the Koninginneweg bureau. We’ve just come from there.’

‘He must have just left Paradiso,’ I said, mainly to myself. And then to him: ‘Could he have taken that footbridge over the canal, towards the Stadhouderskade?’

‘We don’t have any details, sir. Only that the driver of the car remained at the scene of the accident. He phoned the police immediately.’

‘Adri, just get in , will you,’ Miriam said. She was already sitting on the back seat. ‘Before it’s too late.’

I got in next to her.

‘We’ll get you there as fast as possible,’ the policewoman said before slamming the sliding door shut. ‘It’s still early, the A10 won’t be too busy. Although … with the holiday weekend …’

She got in next to her colleague, who had taken his place at the wheel. I pulled the sobbing Miriam up close to me. She was now crying uncontrollably.

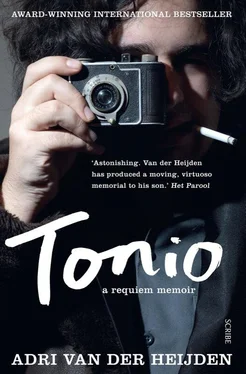

‘Our sweet Tonio … he might be dead already.’

7

H&NE. For more than thirty years, this was my secret code for the woman — even she didn’t know about it — whom I held tight on the back seat of the police van.

‘How’d that rice get into the pasta?’

Miriam’s question, on a warm summer evening in ’79, had set everything in motion. ‘Memory is like a dog that lies down wherever he wants,’ writes Cees Nooteboom. In this case, it cannot have been purely dog-like that there on the back seat, with this shuddering body in my arms, I thought back on the first time I met her. The two police officers up front had more or less dragged us out of bed because Tonio was badly injured — the son that, nine years after that rice in the pasta, we had made together. The child whose life was now in danger. The boy who we were following a terrible, careening path to be with.

The official story that I had foisted on the world began at her birthday party, 23 November 1979, three days after she turned twenty. Not many people know that she had already come into my viewfinder six months earlier.

I wanted to have a short novel finished by the end of the summer, having started it that spring in Perugia. I had hoped to catch up with a young woman, Mara, whom I’d met the previous year in Sicily. I didn’t have her address, but did have a phone number, although I didn’t dare ring her — and so it happened that I just bumped into her on a Perugia street. A hasty and sloppy romance ensued, which was at the very least detrimental to my book. I fled to a tiny island in Lake Trasimeno, with 99 or 102 inhabitants, and set to work. I stayed there until the end of July. On Sundays, Mara came over by ferry. It was a good arrangement, until she started to insist that I join her and a small group of friends on Sardinia for the remainder of the summer holidays. I had nothing against Sardinia, but didn’t much relish six weeks of enforced loafing, especially while the publisher at home was waiting for his text.

So I took the train back to Amsterdam and my stuffy third-floor walk-up in De Pijp. It was a hot summer. In the evening, I’d sit working at my desk in front of the open balcony doors until dusk, not wanting to turn on lights because of the mosquitoes. I was lucky with late-afternoon sunlight: where, according to the architectural logic of the neighbourhood, one would expect a parallel cross-street between the Van Ostadestraat, where I lived, and the houses on Sarphatipark, there was only an expanse of low-rise sheds belonging to an assortment of shops and small businesses. Two doors further along, behind a squatted building, one such shed had been torn down and a sort of wild garden had sprouted up among all the rusty scrap metal and rotting wood. The squatters barbecued there on warm summer evenings. One of them was Hinde, whom I knew because one day she brought me a huge bunch of pink tea-roses as thanks for having let her tap into my water main. I knew she had a younger sister who also hoped to move into the squat, but until then only visited once in a while.

On one of those never-ending summer evenings, Hinde and her housemates organised another barbecue and invited me along. ‘My sister’ll be there, too,’ she said, but I wasn’t sure if it was intended as a fix-up. I politely turned down the invitation. I hadn’t come back from Italy to go to parties: shit, if I wanted to party I could have spent the summer with Mara and Ivana and the rest of them on Sardinia. But my work didn’t amount to much that evening. The barbecue, a rusty three-legged thing, billowed smoke. My balcony, with its open doors, acted like a fireplace flue, so that I spent most of the evening looking at my papers through watering eyes.

‘A rat!’ cried one of the fellows. ‘I just saw a rat. There, by those crates!’

‘Onto the barbecue with him.’ Hinde’s voice, I recognised it already. Laughter from down below.

‘How’d that rice get into the pasta?’ A distant voice that resembled Hinde’s: that had to be the sister.

‘From the salt shaker,’ Hinde called back. ‘The cap came unscrewed.’

The wind was apparently blowing my way, so the sausages and drumsticks on the grill made my mouth water, but it was above all the voices cutting clearly through the fading light that made me regret not being down there, too, where it was alive with rats and girls, and where I would have relished spooning up a mouthful of macaroni-and-rice. I sat there, not doing much myself, listening to their talk and laughter, to the tinkle of clinking glasses, until the bats began to circle above the sheds, and it became altogether too dark to put another letter on paper.

It could have been the swerving of the police van that made me feel slightly queasy, but more likely it was the memory of the desires sparked by that summer evening. Later, that desire got itself a future: Miriam and me … me, Miriam, and Tonio … But this, too, was part of that future: us on our way to the hospital to be told just how critical our boy’s condition was. If he stood a chance. If he was still alive.

8

H&NE. In the late summer or early fall of ’79, one of the backyard barbecue voices got a face.

The squatters’ pad, Van Ostadestraat 205, was next door to a primary school with a playground at the back and a widened sidewalk out front where mothers waited to pick up their brood. This is where I saw her, kick-coasting her granny bike, manoeuvring between clusters of chatting women, some of whom cast her a disapproving glance while stepping demonstratively off to one side. With her left foot resting on the pedal and propelling the bike along with her right foot, she caused just as much inconvenience as regular cycling, except this way the police couldn’t give her a fine.

I had just closed the door to no. 209, where I lived, behind me. I can’t remember if there was a threat or forecast of rain, but the kick-coasting girl wore a raincoat several sizes too big. The garment, in a men’s cut, must have been beige once, but was now shockingly filthy — it was an eye-catcher even in this neighbourhood of dilapidated squats and rusted-through bikes lying half in the gutter. The front was particularly grubby, full of random smudges, while the fabric around the buttons was pretty much black, as though the coat had once done service as a coalman’s apron.

I would have just shrugged it off, were it not for the very pretty head that stuck out of the equally grimy collar, shiny with grease and buttoned up to the chin. Loose, dark hair framed a lightly tanned face that nevertheless gave the impression of paleness, perhaps because of the dark eyes that weren’t even made up (which would have been rather incongruous alongside a coat like that). The oversized garment concealed her figure, but a certain roundness in the chin, neck, and jaw suggested the girl was on the chubby side.

Читать дальше