We bobbed to the left of the players’ boat. There was a gap in the water police’s cordon, which a floating camera crew from the popular show RTL Boulevard took advantage of by cruising right up alongside, so close they could almost touch. The TV glamour-programme crew did its work until Wesley Snijder recognised the presenter’s mug and dumped the contents of a ten-litre beer stein over him. There: payback for the tendentious reporting on Wesley’s fiancée.

The armada sailed past one of the harbour islands.

27

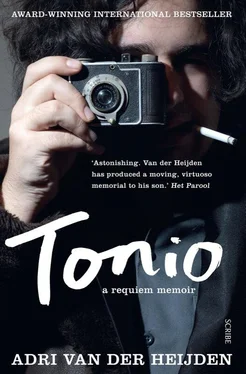

When I woke up that morning, I realised I was wearing my apnea mask. Usually, if I went to bed tanked up — as was certainly the case after that visit to the cemetery — I’d neglect to put it on, sometimes out of forgetfulness, more often because I fell into a deep sleep the minute I lay down. Last night, even though my mind was a blank, I apparently did think of it.

I dreamt of Tonio. As I lay there half asleep, listening to the quiet murmur of the CPAP device, I tried to recall the dream. Tonio cried at the end — no, he was still crying. You could barely hear it above the sound of the machine, but it was unmistakable. He did not cry like a young adult man, no, but like the two-, three-year-old he once was. He cried, quietly and inconsolably sad, as he occasionally did on Thursday evenings in our Leidsegracht days, when Miriam had her regular night out with a girlfriend. I would babysit Tonio, and if he woke up, perhaps because he knew (or felt) that his mother was not there, he cried. If I went to have a look, he would stand up in his crib, which only just fitted in the nook of the roof. Upon seeing his father, he said, with a sniff and a wobbly voice: ‘I want Mummy.’

I couldn’t offer him Mummy, because she was sitting in a restaurant with Lot, or they were having a last drink at Café Schiller. ‘I want Mummy.’ His singsong weeping made me all the more nervous, because on Thursday nights we usually received a couple of anonymous calls. If I answered, it was silent on the other end of the line. Sometimes I thought I heard vague pub noises in the background. I have to admit that at first I suspected it was Miriam: checking whether I was at really at home with the little one. Our relationship was not at its best in those days (even though Our Man in Africa was not yet in the picture). When I brought it up with her, she hit the roof. Never, never would she do such a thing. Didn’t I remember that back when we lived in De Pijp, ten years before, she had been the victim of anonymous telephone terrorism? Whenever she answered, the caller played a German march, or the Horst Wessel. Later, we discovered that the caller was a neo-Nazi in the neighbourhood, a civics teacher at the high school where my sister taught English. A nostalgic anti-Semite.

We assumed that the Thursday-evening caller was a Schiller regular, who wanted to let me know he’d spotted my wife, or wanted to suggest that he himself was in her company — in short, that he had me in his grip. But this suspicion did nothing to relax me in my duties as babysitter, and Tonio was well aware of it, so that he kept on whimpering, almost apologetically softly — a full-out sob session just wasn’t his style. ‘I want Mu-u-u-ummy.’

Meanwhile, that morning, the thirteenth of July, he went on wailing as a continuation of my long-forgotten dream, as only the very occasionally inconsolable Tonio could. For a moment, I thought it was the neighbour’s youngest child, whose early-morning cries I heard from time to time through the open windows. But no, the neighbours were on holiday. And besides, it was unmistakably the weeping of the three-year-old Tonio — so real, so near, that it frightened me. The sound was dampened by the hum of the CPAP machine. I wanted to hear Tonio cry in all his unadulterated misery, so that I’d know what he needed …

I tore off the apnea mask without undoing the plastic hooks. I yanked the elastic bands over my head and hurled the thing, tube and all, onto the floor. The apparatus lay there for a few seconds, making that slurping and sucking sound, and then … silence. The child’s hushed crying had vanished.

In its drowsy state, my brain must have converted the singsong hum of the CPAP into Tonio’s long-ago disquiet. I wanted it back. I wanted to be able to listen to it for hours on end. I groped in the dark next to the bed, found the tube, and pulled the elastic bands back over my head. The apparatus resumed automatically, softly pumping air into the mask, guarding its wearer against suspended breathing. The puffs of air sounded the same as before, but the weeping was gone. I’d driven it off.

All day I tried to call to mind that real-life crying. I am not a great believer in supernatural incidents, but I could not avoid the notion that Tonio, via my apnea machine, was trying to tell me something. Perhaps the terrible, unutterable truth about his end. The suffering he must have endured after being thrown to the asphalt, or later, in the ambulance or on the operating table. Or, declared brain-dead, on his deathbed, when all he was given was air through a breathing tube. Maybe there he felt his parents’ presence, their kisses and caresses, and heard their choked words of farewell. This morning, Tonio tried to say something back. But not comforting. Only how awful it was. The pain. The farewell. And in doing so, he used his most anguished child’s voice. Its melancholy, wordless melody.

28

Much as the police in their bumper-boats tried to keep the pursuing fans’ fleet at bay, our motorised punt remained in the front ranks. We jounced our way into the labyrinth of the city. The very first bridges were already thronged with hysterically bleating supporter-sheep. Compared to June ’88, when the blandness of everyday duds still dotted the red-white-blue, the fans were now far more exuberantly decked out in the colour of their religion. Many of the supporters wore shapeless, bright orange angel-hair wigs, some of them a good half-metre across. The costume director of the film Amadeus would have been jealous.

Seen from a distance, the frizzy offshoots of the wigs bled seamlessly into a powder-like orange mist produced by spray cans. As it hissed out of the valve, the smoke was still a clear day-glo orange; but as it wafted out across the water, the mist quickly took on a grubby tint. It made me think of the crayon I used as a child to colour in a pencil-outlined rooftop. The crayon always dragged some pencil graphite with it, smudging the orange into a dirty grey-red — quite realistic, you could say, but today it only made me sad.

As we turned onto the Brouwersgracht, I felt Miriam poke me in the back. I was being beckoned by the host, who sat at the stern, manning the rudder. He shouted that he wanted to bypass the Herengracht and try to approach Museumplein via Prinsengracht and Spiegelgracht. That would give us a head start.

I nodded, and wondered if I could get to the Hobbemastraat/Stadhouderskade intersection without running into a barricade. We hadn’t told our friends that, for us, that spot was the actual objective of this trip.

The Melkmeisjesbrug was, in all its slenderness, a living triumphal arch, rising up out of a dense, unearthly orange mist. The red-white-blue mass that swarmed over it had a thousand legs and waving tentacles, and it screamed wordlessly from a thousand throats.

The players’ boat, followed by that of the officials, turned left onto the Herengracht directly after passing under the Milkmaids’ Bridge. Our captain picked up speed. The bow of the punt lifted slightly and cleaved the water of the Brouwersgracht. Straight ahead. I glanced to the left. The Herengracht was, for as far as the eye could see, a tunnel formed by a canopy of trees and a mass of writhing arms, all waving flags, banners, and pennants.

Читать дальше