Then I awoke one morning to find blood on the bedsheet. Cassis and Reinette were getting ready to cycle to school and paid little attention to me. Instinctively I dragged the cover over the stained sheet and pulled on an old skirt and sweater before running down to the Loire to investigate my affliction. There was blood on my legs, and I washed it in the river. I tried to make a bandage for myself out of old handkerchiefs, but the injury was too deep, too complex for that. I felt as if I were being torn apart nerve by nerve.

It never occurred to me to tell my mother. I had never heard of menstruation-Mother was obsessively prim regarding bodily functions-and I assumed that I was badly hurt, maybe even dying. A careless fall somewhere in the woods, a poison mushroom, bleeding me from the inside out, perhaps even a poisonous thought. We did not go to church-my mother disliked what she called la curaille and sneered at the crowds on their way to Mass-and yet she had given us a strong awareness of sin. Badness will get out somehow, she would say; and we were full of badness to her, like wineskins bloated with a bitter vintage, always to be watched, tapped, every look and mutter indicative of the deeper, the instinctive badness that we hid.

I was the worst. I understood this. I saw it in my own eyes in the mirror, so like hers with their flat, animal insolence. You can call Death with a single bad thought, she used to say, and that summer all my thoughts had been bad. I believed her. Like a poisoned animal I hid, climbing up to the top of the Lookout Post and lying curled on the wooden floor of the tree house, waiting for death. My belly ached like a rotten tooth. When Death didn’t come I read one of Cassis’s comics for a while, then lay looking up at the bright canopy of leaves until I fell asleep.

She explained it to me later as she handed me the clean sheet. Expressionless but for that look of appraisal which she always wore in my presence, mouth thinned almost to invisibility and eyes barbed-wire jags in her pallor.

“It’s the curse come early,” she said. “You’d better have these.” And she gave me a wad of muslin squares, almost like a child’s diapers. She didn’t tell me how to use them.

“Curse?” I’d stayed away all day in the tree house, expecting to die. Her lack of expression infuriated and confused me. I’d always loved drama. I’d imagined myself dead at her feet, flowers at my head. A marble gravestone- Beloved Daughter . I’d told myself that I must have seen Old Mother without knowing it. I was cursed.

“Mother’s curse,” she said as if in agreement. “You’ll be like me now.”

She said nothing more. For a day or two I was afraid, but I did not speak to her about it, and I washed the muslin squares in the Loire. After that the curse ended for a time, and I forgot about it.

Except for the resentment. It was focused now, honed somehow by my fear and my mother’s refusal to comfort. Her words haunted me- you’ll be like me now -and I began to imagine myself changing imperceptibly, growing more like her in sly insidious ways. I pinched my skinny arms and legs because they were hers. I slapped my cheeks to give them color. One day I cut off my hair-so closely that I nicked the scalp in several places-because it refused to curl. I tried to pluck my eyebrows, but I was unskilled at the task and I had already taken most of them off when Reinette found me, squinting over mirror and tweezers with a deep crease of rage between my eyes.

Mother barely noticed. My story-that I had scorched off my hair and eyebrows trying to light the kitchen boiler-seemed to satisfy her. Only once-this must have been on one of her good days-as we were in the kitchen making terrines de lapin , she turned to me with an oddly impulsive look in her face.

“Do you want to go to the pictures today, Boise?” she asked abruptly. “We could go together. You and me.”

The suggestion was so untypical of my mother that I was startled. She never left the farm except on business. She never wasted money on entertainment. Suddenly I noticed that she was wearing a new dress-as new as those straitened days allowed, anyway-with a daring red bodice. She must have made it from scraps in her room during the nights she couldn’t sleep, because I had never seen it before. Her face was slightly flushed, almost girlish, and there was rabbit blood on her outstretched hands.

I recoiled. It had been a gesture of friendship, I knew that. To reject it was unthinkable. And yet there was too much unspoken stuff between us to make that possible. For a second I imagined going to her, letting her arms come around me, telling her everything…

The thought was immediately sobering.

Telling her what? I asked myself sternly. There was too much to say. There was nothing to say. Nothing at all. She looked at me quizzically.

“Boise? What about it?” Her voice was unusually soft, almost caressing. I had a sudden, appalling picture of her in bed with my father, arms outstretched, with that same look of seduction… “We never do anything but work,” she said quietly. “We never seem to have any time. And I’m so tired…”

It was the first time I ever remember hearing her complain. Again I felt the urge to go to her, to feel warmth from her, but it was impossible. We weren’t used to such things. We hardly ever touched. The idea seemed almost indecent.

I muttered something graceless about having seen the film already.

For a moment the bloodstained hands remained, beckoning. Then her face closed and I felt a sudden stab of fierce exhilaration. At last, in our long, bitter game I had scored a point.

“Of course,” she said tonelessly. There was no more talk of going to the cinema, and when I went to Angers that Thursday with Cassis and Reine to see the very film I had despised earlier, she made no comment. Perhaps she had already forgotten.

That month our arbitrary, unpredictable mother was filled with a new set of caprices. One day cheerful, singing to herself in the orchard as she supervised the last of the picking, the next snapping our heads off if we dared to come near her. There were unexpected gifts-sugar lumps, a precious square of chocolate, the blouse for Reine made of Madame Petit’s famous parachute silk and sewn with tiny pearl buttons. She must have made that in secret too, like the red-bodice dress, for I had never seen her cutting the cloth or fitting it even once, but it was beautiful. As usual, no word accompanied the gift, simply an awkward, abrupt silence in which any mention of thanks or appreciation would have seemed inappropriate.

She wrote in the album:

She looks so pretty. Almost a woman already, with her father’s eyes. If he wasn’t already dead I might feel jealous. Maybe Boise feels it, with her funny little froggy face, like mine. I’ll try to find something to please her. It isn’t too late.

If only she’d said something, instead of setting it down in that tiny, encrypted writing. As it was, these small acts of generosity (if that was what they were) enraged me even more, and I found myself looking for ways to get to her again, as I had that time in the kitchen.

I make no apologies. I wanted to hurt her. The old cliché stands true: children are cruel. When they cut they reach the bone with a truer aim than any adult, and we were feral little things, merciless when we scented weakness. That moment of reaching out in the kitchen was fatal for her, and maybe she knew it, but it was too late. I had seen weakness in her, and from that moment I was unrelenting. My loneliness yawned hungrily inside me, opening deeper and blacker galleries in my heart, and if there were times when I loved her too, loved her with achy, needful desperation, then I banished the thought with memories of her absence, her neglect, her indifference. My logic was wonderfully mad; I would make her sorry, I told myself. I would make her hate me.

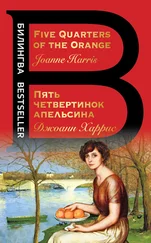

Читать дальше