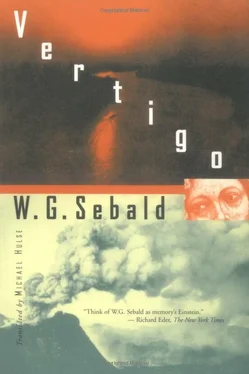

Winfried Sebald - Vertigo

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Winfried Sebald - Vertigo» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2001, ISBN: 2001, Издательство: New Directions, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Vertigo

- Автор:

- Издательство:New Directions

- Жанр:

- Год:2001

- ISBN:978-0811214858

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Vertigo: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Vertigo»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Vertigo

The Emigrants

The Rings of Saturn

The New York Times Book Review

The Emigrants

Vertigo — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Vertigo», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The buffet at Santa Lucia station was surrounded by an infernal upheaval. A steadfast island, it held out against a crowd of people swaying like a field of corn in the wind, passing in and out of the doors, pushing against the food counter, and surging on to the cashiers who sat some way off at their elevated posts. If one did not have a ticket, one had to shout up to these enthroned women, who, clad only in the thinnest of overalls, with curled-up hair and half-lowered gaze, appeared to float, quite unaffected by the general commotion, above the heads of the supplicants and would pick out at random one of the pleas emerging from this crossfire of voices, repeat it over the uproar with a loud assurance that denied all possibility of doubt, and then, bending down a little, indulgent and at the same time disdainful, hand over the ticket together with the change. Once in possession of this scrap of paper, which had by now come to seem a matter of life and death, one had to fight one's way out of the crowd and across to the middle of the cafeteria, where the male employees of this awesome gastronomic establishment, positioned behind a circular food counter, faced the jostling masses with withering contempt, performing their duties in an unperturbed manner which, given the prevailing panic, gave an impression of a film in slow motion. In their freshly starched white linen jackets, this impassive corps of attendants, like their sisters, mothers and daughters at the cash registers, resembled some strange company of higher beings sitting in judgement, under the rules of an obscure system, on the endemic greed of a corrupted species, an impression that was reinforced by the fact that the buffet reached only to the waists of these earnest, white-aproned men, who were evidently standing on a raised platform inside the circle, whereas the clients on the outside could barely see over the counter. The staff, remarkably restrained as they appeared, had a way of setting down the glasses, saucers and ashtrays on the marble surface with such vehemence, it seemed they were determined to all but shatter them. My cappuccino was served, and for a moment I felt that having achieved this distinction constituted the supreme victory of my life. I surveyed the scene and immediately saw my mistake, for the people around me now looked like a circle of severed heads. I should not have been surprised, and indeed it would have seemed justified, even as I expired, if one of the white-breasted waiters had swept those severed heads, my own not excepted, off the smooth marble top into a knacker's pit, since every single one of them was intent on gorging itself to the last. A prey to unpleasant observations and far-fetched notions of this sort, I suddenly had a feeling that, amid this circle of spectres consuming their colazione, I had attracted somebody's attention. And indeed it transpired that the eyes of two young men were on me. They were leaning on the bar across from me, the one with his chin propped in his right hand, the other in his left. Just as the shadow of a cloud passes across a field, so the fear passed across my mind that these two men who were looking at me now had already crossed my path more than once since my arrival in Venice. They had also been in the bar on the Riva where I had met Malachio. The hands of the clock moved towards half past ten. I finished my cappuccino, went out to the platform, glancing back over my shoulder now and then, and boarded the train for Milan as I had intended.

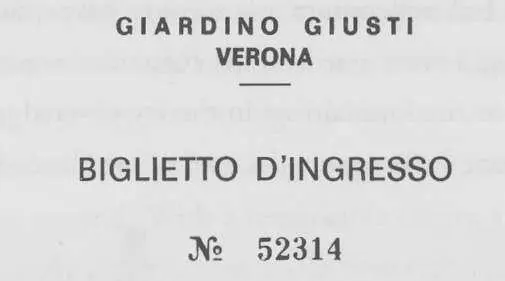

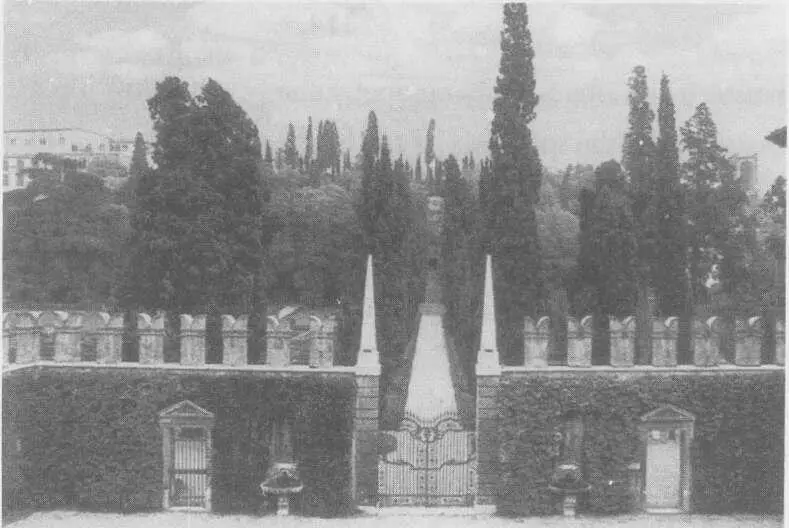

I travelled as far as Verona, and there, having taken a room at the Golden Dove, went immediately to the Giardino Giusti, a long-standing habit of mine. There I spent the early

hours of the afternoon lying on a stone bench below a cedar tree. I heard the soughing of the breeze among the branches and the delicate sound of the gardener raking the gravel paths between the low box hedges, the subtle scent of which still filled the air even in autumn. I had not experienced such a sense of well-being for a long time. Nonetheless, I got up after a while. As I left the gardens I paused to watch a pair of white Turkish doves soaring again and again into the sky above the treetops with only a few brisk wing-beats, remaining at those blue heights for a small eternity, and then, dropping with a barely audible gurgling call, gliding down on the air in sweeping arcs around the lovely cypresses, some of which had been growing there for as long as two hundred years. The everlasting green of the trees put me in mind of the yews in the churchyards of the county where I live. Yews grow more slowly even than cypresses. One inch of yew wood will often have upwards of a hundred annual growth rings, and there are said to be trees that have outlasted a full millennium and seem to have quite forgotten about dying. I went out into the forecourt, washed my face and hands at the fountain set in the ivy-covered garden wall, as I had done before going in, cast a last glance back at the

garden and, at the exit, waved a greeting to the keeper of the gate, who nodded to me from her gloomy cabin. Across the Ponte Nuovo and by way of the Via Nizza and the Via Stelle I walked down to the Piazza Bra. Entering the arena, I suddenly had a sense of being entangled in some dark web of intrigue. The arena was deserted but for a group of late-season excursionists to whom an aged cicerone was describing the unique qualities of this monumental theatre in a voice grown thin and cracked. I climbed to the topmost tiers and looked down at the group, which now appeared very small. The old man, who could not have been more than four feet, was wearing a jacket far too big for him, and, since he was hunchbacked and walked with a stoop, the front hem hung down to the ground. With a remarkable clarity, I heard him say, more clearly perhaps than those who stood around him, that in the arena one could discern, grazie a un'acustica perfetta, l'assolo più impalpabile di un violino, la mezza voce più eterea di un soprano, il gemito più intimo di una Mimi morente sulla scena. The excursionists were not greatly impressed by the enthusiasm for architecture and opera evinced by their misshapen guide, who continued to add this or that point to his account as he moved towards the exit, pausing every now and then as he turned to the group, which had also stopped, and raising his right forefinger like a tiny schoolmaster confronting a pack of children taller by a head than himself. By now the evening light came in very low over the arena, and for a while after the old man and his flock had left the stage I sat on alone, surrounded by the reddish shimmer of the marble. At least I thought I was alone, but as time went on I became aware of two figures in the deep shadow on the other side of the arena. They were without a doubt the same two young men who had kept their eyes on me that morning at the station in Venice. Like two watchmen they remained motionless at their posts until the sunlight had all but faded. Then they stood up, and I had the impression that they bowed to each other before descending from the tiers and vanishing in the darkness of the exit. At first I could not move from the spot, so ominous did these probably quite coincidental encounters appear to me. I could already see myself sitting in the arena all night, paralysed by fear and the cold. I had to muster all my rational powers before at length I was able to get up and make my way to the exit. When I was almost there I had a compulsive vision of an arrow whistling through the grey air, about to pierce my left shoulderblade and, with a distinctive, sickening sound, penetrate my heart.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Vertigo»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Vertigo» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Vertigo» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.