Winfried Sebald - Vertigo

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Winfried Sebald - Vertigo» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2001, ISBN: 2001, Издательство: New Directions, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Vertigo

- Автор:

- Издательство:New Directions

- Жанр:

- Год:2001

- ISBN:978-0811214858

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Vertigo: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Vertigo»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Vertigo

The Emigrants

The Rings of Saturn

The New York Times Book Review

The Emigrants

Vertigo — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Vertigo», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In the summer of 1987, seven years after I fled from Verona, I finally yielded to a need I had felt for some time to repeat the journey from Vienna via Venice to Verona, in order to probe my somewhat imprecise recollections of those fraught and hazardous days and perhaps record some of them. On this occasion in the midst of the holiday season, the night train from Vienna to Venice, on which in the late October of 1980 I had seen nobody except a pale-faced schoolmistress from New Zealand, was so overcrowded that I had to stand in the corridor all the way or crouch uncomfortably among suitcases and rucksacks, so that instead of drifting into sleep I slid into my memories. Or rather, the memories (at least so it seemed to me) rose higher and higher in some space outside of myself, until, having reached a certain level, they overflowed from that space into me, like water over the top of a weir. Once I had begun to write, the time passed more swiftly than I should ever have thought possible, and it was not until the train was rolling slowly from Mestre over the railway causeway, crossing the lagoon which stretched out on either side in the gleam of the night, that I came to. At Santa Lucia I was one of the last to get out. With my blue canvas bag slung as ever across my shoulder, I slowly walked down the platform to the station hall, where a veritable army of backpackers were lying on the stone floor in sleeping-bags on straw mats, close to each other like an alien people resting on their way through the desert. Out in the station forecourt, too, countless young men and women lay in groups or couples or singly, on the steps and all around. I sat on the Riva and took out my writing materials, the pencil and the fine-ruled paper. The red glow of dawn was already breaking over the eastward roofs and domes of the city. Here and there, sleepers stirred in the no man’s land where they had spent the night, propped themselves up and began to rummage through their belongings, eating a bite or drinking a little and then stowing it all carefully away again. Presently, bowed under heavy packs, which reached a full head above them, several began moving among their brothers and sisters still lying on the ground, as if they were preparing for the next stage of an arduous and never-ending journey.

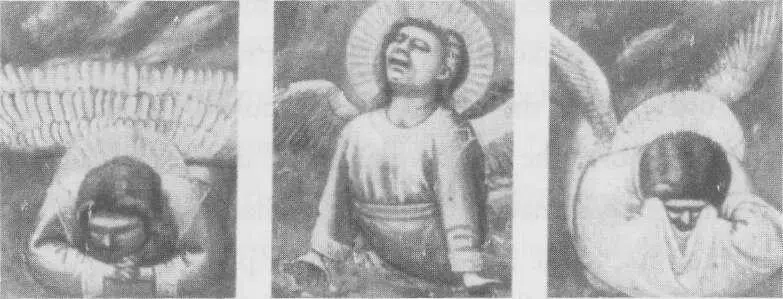

I sat on the Fondamenta Santa Lucia until half the morning was gone. The pencil flew across the paper, and from time to time a cockerel crowed from its cage on the balcony of a house across the canal. When I looked up once again from my work, the shadowy forms of the sleepers on the station forecourt had all vanished, or had faded away, and the morning traffic had begun. At one point a barge laden with heaps of rubbish came by. A large rat scuttled along its gunnel and, having reached the bow, plunged head first into the water. I cannot say whether it was the sight of this that made me decide not to stay in Venice but to travel on to Padua instead, without delay, and seek out Enrico Scrovegni's Arena Chapel. Hitherto all I knew of it was an account that described the undiminished intensity of the colours in Giotto's frescoes, and the certainty which governs every stride and feature of the figures represented. Once I entered the chapel, from the heat that already prevailed in the city even in the early morning of that day, and stood before the three rows of frescoes that cover the walls up to the ceiling, I was overwhelmed by the silent lament of the angels, who have kept their station above our endless calamities for nigh on seven centuries. Their lament resounded in the very silence of the chapel and their eyebrows were drawn so far together in their grief that one might have supposed them blindfolded. And are not their white wings, I thought, with those few

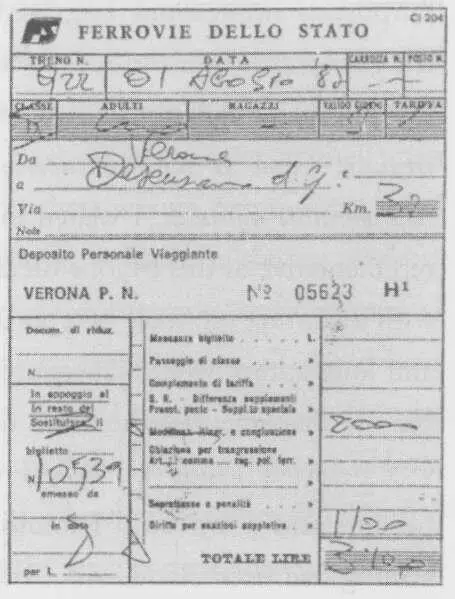

bright green touches of Veronese earth, the most wondrous of all the things we have ever conceived of? Gli angeli visitano la scena della disgrazia — with these words on my lips I returned through the roaring traffic to the station, not far from the chapel, to take the very next train to Verona, where I hoped to learn something not only relating to my own abruptly broken-off stay in that city seven years before but also about the disconcerting afternoon, as he himself described it, that Dr K. spent there in September 1913 on his way from Venice to Lake Garda. After barely an hour of breezy travel, with the windows open upon the radiant landscape, the Porta Nuova came into view and as I beheld the city lying in the semicircle of the distant mountains, I found myself incapable of alighting. Strangely transfixed, I remained seated, and when the train had left Verona and the guard came down the corridor once more I asked him for a supplementary ticket to Desenzano, where I knew that on Sunday the 21st of September, 1913, Dr K., filled with the singular happiness of knowing that no one suspected where he was at that moment, but otherwise profoundly disconsolate, had lain alone in the grass on the lakeside and gazed out at the waves in the reeds.

The railway station at Desenzano, which cannot have been completed much before 1913 and which, at least externally, had changed little since, lay 'deserted in the midday sun when the departing train had shrunk to the size of the westerly vanishing point. Above the tracks, which ran towards the horizon in a straight line as far as the eye could see, the air shimmered. To the south were open fields. The station building, deserted though it seemed, gave a decidedly purposeful impression. Engraved in elegant lettering into the glass panels over the doors which faced the platform were the official designations of the station staff. Capo stazione titulare. Capo di statione superiore. Capi stazione aggiunti. Manovratori manuali. I waited in the hope that at least one representative of this bygone hierarchy, say, the stationmaster with a glinting monocle or a porter with a walrus moustache and long apron, would emerge from one of those doors and bid me welcome, but there was no sign of life. The building was deserted inside as well. For some time I wandered upstairs and down until I found the pissoir, where scarcely a thing had been altered since the turn of the century, as in the rest of the building. The wooden stalls in a military shade of green, the heavy stoneware basins and the white tiles had aged, were chipped and netted with hairline cracks, but otherwise everything was unchanged, except for the graffiti, all of which dated from the last twenty years. As I washed my hands I looked in the mirror and wondered whether Dr K., travelling from Verona, had also been at this station and found himself contemplating his face in this mirror. It would not have been surprising. And one of the graffiti beside the mirror seemed indeed to suggest as much. Il cacciatore, it read, in awkwardly formed letters. When I had dried my hands, I added the words nella selva nera.

Later on, I sat on a bench in the square outside the station for about half an hour, and had an espresso and a mineral water. It was good to sit in the shade, at peace in the middle of the day. But for a few taxi drivers dozing in their cabs and listening to their radios, there was no one in sight, until a carabiniere drove up, left his vehicle in the no parking zone immediately in front of the entrance, and disappeared into the station. When he emerged again, all the drivers got out of their taxis, as if at a signal, surrounded the somewhat undersized and slightly built policeman, whom they had perhaps known at school, and upbraided him on account of the illegal way he had parked. Barely had one said his piece but the next one began. The carabiniere could not get a word in, and whenever he tried he was promptly talked down. Helplessly, and even with a certain panic in his eyes, he stared at the accusing forefingers pointed at his chest. But since the entire performance merely served the taxi drivers as a timely diversion to dispel the midday boredom, their victim, for whom these accusations plainly went against the grain, could make no serious objection, not even when they set about faulting his posture and putting his uniform to rights, solicitously brushing the dust off his collar, straightening his tie and cap, and even adjusting his waistband. At length one of the drivers opened the police car door, and the guardian of the law, his dignity somewhat impaired, had no option but to climb in and drive off, tyres squealing, around the circle and down Via Cavour. The taxi drivers waved him off and stood around long after he was out of sight, reliving this or that part of the comedy, quite beside themselves with merriment.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Vertigo»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Vertigo» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Vertigo» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.