A lot of that has since been refuted, if I’m not mistaken .

That’s of no concern to me; for that great text corroborated and rescued me completely. Why would I be interested in facts? Kant cannot be refuted any more than an oak tree can be refuted. It grew and spread and it stands there, but there are times when we need it in order to stay in its shade and marvel at it, like at a great encouraging example.

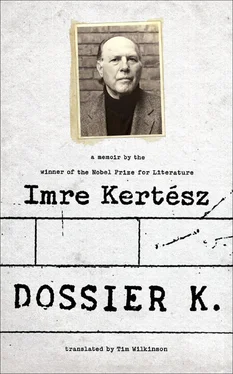

That sounds rather like a credo, which is quite unusual coming from you. So, as you have already mentioned, in 1960 you start writing Fatelessness. You were thirty years old at the time and, on the evidence of the photographs, a determined young man in good shape, who, according to what is in effect the final chapter of Fiasco, does not wish to take the chance to escape “from this city which denied all hope, this life that belied all hope: ‘Where to?’ asked Köves, at a loss to understand,… ‘Does it matter?’ Sziklai fumed. ‘Anywhere!’ … He set off again. ‘Abroad,’ he added, and in Köves’s ears the word, at that instant, sounded like a festive peal of bells. He walked on for a while without a word, his head hung in thought, by Sziklai’s side. ‘Sorry, but I can’t go,’ he said eventually. ‘Why not?’ Sziklai again came to a stop, astonishment written all over his face. ‘Don’t you want to be free?’ he asked. ‘Of course I do,’ said Köves. ‘The only trouble is,’ he broke into a smile, as if by way of an apology, ‘I have to write a novel.’ ‘A novel?!’ Sziklai was dumbstruck. ‘Now of all times? … You can write it later, somewhere else,’ he went on. Köves continued smiling awkwardly: ‘Yes, but this is the only language I know,’ he worried. ‘You’ll learn another one,’ Sziklai said, waving that aside … ‘By the time I learn one I’ll have forgotten my novel.’ ‘Then you’ll write another one,’ Sziklai’s voice by now sounded almost irritated, and it was more for the record than in hope of being understood that Köves pointed out: ‘I can only write the one novel that it is given me to write’ … They stood wordlessly, facing each other in the street, a storm of shouts of ‘We want to live!’ around them,… then they swiftly embraced. Sziklai was then swallowed up in the crowd, whereas Köves turned on his heels and set off back at a shambling pace, like someone who is in no hurry as he already suspects in advance all the pain and shame his future holds for him.” I have deliberately quoted from this scene because, for all its grotesqueness, I nevertheless feel it is very true to life .

Rightly so. I think all big decisions are, in truth, as grotesque as that.

I wonder why .

Because they are inexplicable. You have to choose between bombast and silence.

I have the feeling that in light of The Union Jack there is no need for us to say anything more about 1956. The late Sixties were characterized by a national collective amnesia, the emergence of a Hungarian society which was derided as “goulash communism” that you yourself have referred to, here and there, as “the intellectual swamp of the Brezhnev era” or “the West’s favourite brand of Communism.”

Yes, that was when I noticed the emergence of a collective morality (or rather immorality) of the functional man, and of fatelessness.

In Galley Boat-Log one can read lengthy analyses 32 about this discovery, about functional man being “an insubstantial being at the mercy of totalitarianism.” Then in Liquidation one of the characters speaks about a separate “species” of survivors: “… we are all survivors; that is what determines our perverse and degenerate mental world. Auschwitz. Then the forty years that we have put behind us since.” What I am particularly interested in, right now, is what you mean by a “collective morality.”

That peculiarly Hungarian consensus that blossomed in the name of survival and, in essence, was founded on an “acceptance of realities,” so-called.

Realities that included the Kádár regime, installed after the crushing of the 1956 revolution …

Yes, that cheap conformity that undermined every moral and intellectual stand, that petit-bourgeois police state that called itself socialist but which regarded that docile and corrupt, simpering and authoritarian, mind-numbing, semifeudal, semi-Asiatic, militaristic Horthyite society, governed from the handsomely built dictator’s waistcoat pocket, as its true model.

According to the witticism of the day, Hungary still counted as “the happiest barrack in the socialist camp.”

If I were really looking to be ironic, I would call it the country that, in the course of its historical evolution, lived through enlightened absolutism in the late eighteenth century and has now got as far as liberal totalitarianism.

“World time,” you write in Galley Boat-Log, “that blindly ticking machine, which has been dropped in the quagmire hereabouts and is now overrun by masses of sprightly Lilliputians, who are busy trying to dismantle the appliance, or at least silence it.” 33

And in so doing provincial stillness set in; the stillness of the Kádár regime.

Still, perhaps even that had its good side, didn’t it? You need stillness to write a novel, don’t you?

That’s one way of looking at it: one could pull oneself back as far as was possible. That was one of the reasons I stayed in Hungary at the end of 1956: the low cost of living and a safe hiding place. Albina pleaded that we should go …

May one ask if you ever regretted not listening to her?

You may ask, but there is no answer.

You have said that it was the language, first and foremost, that bound you to Hungary; but then, on the other hand, what has become clear so far is that you gained your most stunning literary experiences, virtually without exception, from foreign writers, whether in good or bad translation. Did no Hungarian traditions have an impact on you?

It seems not. Only later did I become acquainted with Gyula Krúdy and Dezs? Szomory, whose prose I greatly love and admire; Géza Ottlik or Iván Mándy, or indeed even Sándor Márai, whose books were available only as contraband items, were still unknown to me.

Does that go any way to explaining the foreignness of the language of Fatelessness?

No, the foreignness of the language of Fatelessness is explained solely by the foreignness of the subject and the narrator.

What I seeking for an answer to is how you “managed” so totally to marginalize yourself in the intellectual life of Hungary that you could hardly be said to have been present at “the sidelines,” to use one of Iván Mándy’s categories .

During the Kádár era that was more or less the limit of my ambition.

If one pays close attention, certain pages of Galley Boat-Log attest to the fact that your unnatural situation took a greater toll on you than you may have been prepared to admit even to yourself .

You know, there’s a kind of syndrome to which I have given the name “dictatorship schizophrenia.” Every artist longs for recognition, though he is well aware that it is precisely what he doesn’t want. He finds it hard, however, to resign himself to the fact that he has created a work of art that nobody takes any notice of. One incident that happened to me was that an unknown colleague addressed me in the corridor of the writer’s retreat at Szigliget. He must have arrived not long before, because I hadn’t seen him around. “Are you Imre Kertész?” “Yes, I am.” “You wrote Fatelessness ?” “I did.” Whereat, he embraced me and rained kisses on my cheeks — he was a tall and beefy man, so I had a job pulling myself away from him. He lauded the book at length, and in a far from unintelligent way. It was only then that I discovered who his nibs was: one of the Party’s chief ideologists, a chief censor, what was then called a super-Reader, the highest court of appeal in matters of suspect manuscripts. He was editor-in-chief of some critical journal in which, following his abounding enthusiasm, he got an anonymous author to write a noncommittal review that was printed in a well-hidden corner of the journal devoted to brief notifications of insignificant books.

Читать дальше