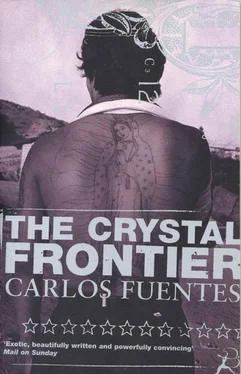

Carlos Fuentes

The Crystal Frontier

1

“There is absolutely nothing of interest in Campazas.” The Blue Guide’s categorical statement made Michelina Laborde smile slightly, disturbing for a moment the perfect symmetry of her face. Her “little Mexican mask” a French admirer had called it — the perfect bones of Mexican beauties who seem immune to the ravages of time. Perfect faces for death, added the admirer, which Michelina did not like one bit.

She was a young woman of sophisticated tastes because she’d been educated that way, brought up that way, and refined that way. She was of an “old family,” so even a hundred years earlier her education would not have been very different. “The world has changed, but we haven’t,” her grandmother, still the pillar of the household, would say. Except that there used to be more power behind the breeding. There were haciendas, demurral courts — for throwing out perfectly good lawsuits “that did not warrant legal action”—and Church blessings.

There were also crinolines. It was easier then to cover up the physical defects that modern fashions reveal. Blue jeans accentuate a fat backside or thin legs. “Our women are like thrushes,” she could still hear her uncle (May he rest in peace) say. “Thin shanks, fat asses.”

She imagined herself in crinolines and felt herself freer than she did in jeans. How wonderful, knowing you were imagined, hidden, that you could cross your legs without anyone’s noticing, could even dare to wear nothing under your crinolines, could feel the cool, free breeze on those unmentionable buttocks, on the very interstices of modesty, aware all the while that men had to imagine it! She hated the idea of going topless at the beach; she was a declared enemy of bikinis and only reluctantly wore miniskirts.

She was blushing at these thoughts when the Grumman stewardess came by to whisper that the private jet would soon be landing at the Campazas airport. She tried to find a city somewhere in that panorama of desert, bald mountains, and swirling dust. She could see nothing. Her gaze was captured by a mirage: the distant river and, beyond it, golden domes, glass towers, highway cloverleafs like huge stone bows. But that was on the other side of the crystal frontier. Over here, below — the guidebook was right — there was nothing.

Her godfather, Don Leonardo, met her. He’d invited her after their meeting in the capital just six months earlier. “Come take a look at my part of the country. You’ll like it. I’ll send my private plane to get you.”

She liked her godfather. He was fifty years old — twenty-five years older than she — and robust, half-bald, with bushy sideburns but the perfect classic profile of a Roman emperor and the smile and eyes to go with it. Above all, he had those dreamy eyes that said, I’ve been waiting a long time for you.

Michelina would have rejected pure perfection; she’d never met an extremely handsome man who hadn’t disappointed her. They felt they were better looking than she was. Good looks gave them unbearably domineering airs. Don Leonardo had a perfect profile, but it was offset by his cheeks, his baldness, his age. His smile, on the other hand, said, Don’t take me too seriously — I’m a sexy, fun-loving guy. And yet his gaze, again, possessed an irresistible intensity. I fall in love seriously, it said to her. I know how to ask for everything because I also know how to give everything. What do you say?

“What’s that you’re saying, Michelina?”

“That we met when I was born, so how can you tell me that only six months ago we—”

He interrupted her. “This is the third time I’ve met you, dear. Each time it seems like the first. How many more times do I get?”

“Many more, I hope,” she said, without thinking that she would blush — although, since she’d just spent ten days on the beach in Zihuatanejo, no one would have been able to tell if she was turning red or was simply a little sunburned. But she was a woman who filled the space wherever she happened to be. She complemented places, making them more beautiful. A chorus of macho whistles always greeted her in public places, even in the small Campazas airport. But when the lover boys saw who was with her, a respectful silence reigned.

Don Leonardo Barroso was a powerful man here in the north as well as in the capital. For the most obvious reasons, Michelina Laborde’s father had asked Don Leonardo, the then minister, to be her godfather: protection, ambition, a tiny portion of power.

“Power!”

It was ridiculous. Her godfather himself had spelled things out for them when he was in the capital six months before. Mexico’s health depends on the periodic renewal of its elites. For good or ill. When native aristocracies overstay their welcome, we kick them out. The social and political intelligence of the nation consists in knowing when to retire and leave open the doors of constant renewal. Politically, the “no reelection” clause in the constitution is our great escape valve. There can be no Somozas or Trujillos here. No one is indispensable. Six years in office and even the president goes home. Did he steal a lot? So much the better. That’s the price we pay for his knowing when to retire and never say a word again. Imagine if Stalin had lasted only six years and had peacefully turned power over to Trotsky, and he to Kamenev, and he to Bukharin, et cetera. Today the USSR would be the most powerful nation on earth. Not even the king of Spain gave hereditary titles to Mexican creoles, and the republic never sanctioned aristocracies.

“But there have always been differences,” interrupted Grandmother Laborde, who was seated across from her cases of curios. “I mean, there have always been ‘decent’ people. But just think: there are people who presume to be of the Porfirio Díaz-era aristocracy — all because they lasted thirty years in power. Thirty years is nothing! When our family saw Porfirio Diaz’s supporters enter the capital after the Tuxtepec revolution, we were horrified. Who were these disheveled men from Oaxaca and these Spanish grocers and French sandal makers. Porfirio Díaz! Corcueras! Nonsense! Limantours! An arriviste! In those days, we decent people followed Lerdo de Tejada.”

Michelina’s grandmother is eighty-four years old and is still going strong. Lucid, irreverent, and anchored by the most eccentric of powers. Her family lost influence after the revolution of 1910-20, and Doña Zarina Ycaza de Laborde took refuge in the curious hobby of collecting junk, bits and pieces of things, and, most of all, magazines. Every single doll (male or female) that enjoyed popularity — whether it was Mamerto the Charro or Chupamirto the Tramp, Captain Shark, or Popeye — she would rescue from oblivion, filling an entire armoire with those cotton-stuffed figures, repairing them, sewing them up when their innards spilled out.

Postcards, movie posters, cigar boxes, matchboxes, bottlecaps, comic books — Doña Zarina collected all of them with a zeal that drove her children and even her grandchildren to despair, until an American company specializing in memorabilia bought her complete collection of Today, Tomorrow, and Always magazines for something like $50,000. Then they all opened their eyes: in her drawers, in her armoires, the old lady was stashing away a gold mine, the silver of memory, the jewels of remembrance. She was the czarina of nostalgia (as her most cultured grandson aptly put it).

Doña Zarina’s gaze clouded over as she looked out from her house on Rio Sena Street. If the city had been taken care of as well as she had maintained the Minnie Mouse doll… But it was better not to speak of such things. She had remained and witnessed the paradoxical death of a city that as it grew bigger diminished, as if it were a poor being who was born, grew, and inevitably died. She plunged her nose back into the sets of bound volumes of Chamaco Chico and did not expect anyone to hear or understand her lapidary phrase: “Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.”

Читать дальше