but on the other side, trying to cross the bridge amid great confusion, two naked men approach the immigration kiosks, a fifty-year-old, silvery hair, athletic physique but well-fed, dragging a scrawny simpleton by the arm, the simpleton screwed up beyond all screwing up, just skin and bones, dark, but the two of them together, pleading, they seem like lunatics, they didn’t let us leave through San Diego and come in through Tijuana, or leave through Caléxico and come in through Mexicali, or leave through Nogales Arizona and come in through Nogales Sonora,

where are they going to send us?

to the sea?

are we going to swim our way to Mexico?

with nothing on, stripped, cleaned out?

give us a place to rest, in the name of heaven!

don’t you realize that behind us, pursuing us, armed garbage,

death with deodorant, is approaching and that toward us is advancing once again the dead earth, the unjust earth, the law that says: Shoot fugitives in the back!

we want to enter to tell the story of the crystal frontier before it’s too late,

let everyone speak,

speak, Juan Zamora, bent over, attending a corpse,

speak, Margarita Barroso, showing your uncertain identity so as to cross the border,

speak, Michelina Laborde, stop screaming, think about your husband, the abandoned boy, Don Leonardo Barroso’s heir, imagine yourself, Gonzalo Romero, that the skinheads didn’t murder you but instead the coyotes that now surround your corpse and the corpses of the twenty-three workers in a circle of inseparable hunger and astonishment,

get pissed off, Serafín Romero, and tell yourself you’re going to attack as many damn trains as cross your path so that war can return to the frontier again, so that it’s not only the gringos who attack,

adjust your night-vision glasses, Dan Polonsky, hoping that the strikers dare to take a step forward,

pretend you’re stupid, Mario Islas, so that your godson Eloíno can run inland, wetback, young, breathless, intending never to return,

raise your arms, Benito Ayala, offer your arms to the river, to the earth, to everything that needs your strength to live, to survive,

toss the papers in the air, José Francisco, poems, notes, diaries, novels, let’s see where the wind takes the sheets of paper, let’s see where they fall, on which side, this one or that one,

to the north of the río grande,

to the south of the río bravo,

toss the papers as if they were feathers, ornaments, tattoos to defend them from the inclemency of the weather, clan markings, stone collars, bone, conch, diadems of the race, waist and leg adornments, feathers that speak, José Francisco,

to the north of the río grande,

to the south of the río bravo,

feathers emblematic of each deed, each battle, each name, each memory, each defeat, each triumph, each color,

to the north of the río grande,

to the south of the río bravo,

let the words fly,

poor Mexico,

poor United States,

so far from God,

so near to each other

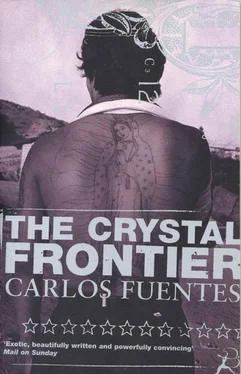

Carlos Fuentes, Mexico’s leading novelist, was born in 1928. He has taught at many universities in the United States and has written essays and screenplays, political journalism and commentary. He has been his country’s ambassador to France and is the author of more than ten novels, including The Death of Artemio Cruz, The Old Gringo and Diana, The Goddess Who Hunts Alone. In 1987, he was awarded the Cervantes Prize, the highest honour given to a Spanish-language writer. His most recent book is A New Time for Mexico.