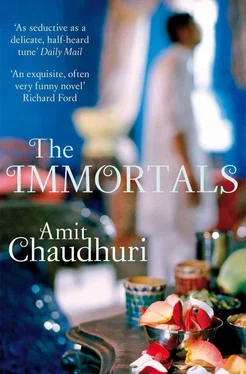

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

This seemed to both Shyamji and his family to be a windfall, a great opportunity. The lady, wan, but always in tasteful, expensive saris, the grey in her hair touching her with an added dignity, began to become more and more visible with Shyamji, with the special, concentrated manner that marks the visitor, a lady with some purpose — perhaps no more than to be in Shyamji’s proximity — listening to him, waiting during a recording, discussing something quickly, even, sometimes, self-effacingly going over a song she’d learnt from him. After seeing her in three different places, Nirmalya hummed to his mother: ‘Who is she?’ ‘I cannot remember her name,’ she confessed. ‘She is a student of Shyamji’s from England.’ Nirmalya had overheard her clear her throat and sing once, shyly. ‘Why does he waste his time with the likes of her?’ he asked, the stringent puritan in him provoked. England meant pounds, and pounds were a windfall; they had the power to heal, to renew. ‘Jao, jao, don’t think so much,’ said Shyamji’s mother. But he wasn’t thinking; he’d decided to take up the offer — in his courteous, patient way, he had the passport and visa done with Mrs Lakhani’s help. Secretly, he was pleased to be free of his family for the first time, of the gaggle with its needs and requirements and opinions — from his revered mother to that loiterer and dramabaaz Pyarelal. It would be like a rehearsal of sannyas, the last stage when the householder withdraws from worldly duties, except that he wasn’t retiring to the forest, he was off to Frognall Lane: the trip had some of the benefits of renunciation, and also made good business sense. He underwent a transformation; for the passport photo, he abandoned his loose pyjamas and kurta and wore a shirt and trousers. He looked more efficient in this incarnation. He felt more efficient, too.

The time of departure was 3 a.m. ‘There’s no point in sleeping,’ said Shyamji with weary reasonableness to his family. ‘Haa, Shyam, you sleep on the plane or when you get there. We’ll sleep when you’ve gone,’ said his mother, even-voiced, hiding some complex apprehension, looking at no one in particular through her thick glasses.

He was leaving on a Saturday; so they rented a VCR from a man on Friday, and two video cassettes, Dharam Karam and Namak Halal , from one of the stifling video libraries that had sprung up irrepressibly in the interstices of the new buildings, and had brief and bright lives, like fireflies. By eight o’clock the packing was done, various white kurtas and pyjamas and handkerchiefs put in, the puja finished and a red tilak embossed on Shyamji’s forehead; they all, Banwari’s and Pyarelal’s families included, huddled in front of the television set, adults and children spilling on to one another, and began to watch a bad copy of Dharam Karam . The volume was high; they seemed unaware of this, and laughed and shouted to each other above the dialogue and violins, talking much of the time, because they’d seen it before; the film wasn’t meant primarily to be watched; it was a participant in this gathering as much as they were. Food arrived in the midst of all this, rotis that had swelled in Neeta’s deft hands, and vegetables, and, once more, the remnants of the yoghurt that had been set overnight in a bowl made of stainless steel. By the time Dharam Karam was over, their eyes ached with the trembling pictures and Banwari felt a bit ill; Shyamji’s son Sanjay took out the cassette and lifted the flap and shook his head at the faint line running through the tape; yet they persisted with Namak Halal , pushing it into the VCR and watching, agog, as it disappeared into the slot. Sumati laughed with recognition as the titles came on; Shyamji, sitting on an armchair, was now watching the film, and was now elsewhere; his mind travelled far away, then came back to the ear-splitting dialogue (the volume was turned up so they could hear it over their own exchanges), to the room, with everyone in it, abruptly. He was already in a state of departure, but sleep, which he’d dismissed from the occasion, was returning to him like an old habit; he yawned twice, and no one in the loud room noticed. When the film was only halfway through, becoming festive and precipitous a little after midnight, Banwari softly reminded him, ‘Bhaisaab, we should leave.’

* * *

MRS LAKHANI’S home was a two-storeyed house with a garden at the back. She manoeuvred the car dexterously into an expectant space in the front; there seemed to be no garage. Then they — she and a curious but slowly acclimatising Shyamji — both got out into the sunlight and shut the doors. A passage on the right, a small half-lit sliver, disappeared somewhere — to the garden, Shyamji found out later. Light came in from that garden into the sitting room. Shyamji had never encountered such silence before, so much composure; so many things everywhere, and not one that looked out of place — the cushions on the sofa, the beer mugs, the plates with pictures of places on them, the orderly crowd of framed photos of ancestors and the Sai Baba and children and grandchildren, a copy of the Radio Times , a large upside-down face emblazoned on its cover, upon the table before the sofa. The air had a curious, still smell that was faintly familiar to him and confused him: cumin and asofoetida.

He liked the silence immediately; it didn’t oppress him. The next morning he opened his eyes early, and stared at the wall opposite him with a mixture of surprise and panic, but after that, once he heard Mrs Lakhani call out, ingenuously, ‘Guruji?’ from the kitchen, he quickly, obligingly, exorcised his disorientation and grew used to the weather, the duration of the day. He was happy, in a way carefully contained but spontaneously childlike, to be free of the cacophony he’d left behind. Here, in this weather, he had a momentary but strong premonition of being able to give his music a home, a sanctuary.

She brought him to the harmonium on the upper storey that two years ago she’d ordered and had shipped from India. It too had made a journey, but it had merged into its home and internalised the hardly-broken stillness in the little children’s room, empty now. Shyamji ran his fingers over the keys almost blithely; and, finding them alien and hard, furrowed his brow and attacked them with a bit more aggressiveness. Then the instrument and he had made their peace, and he was ready to give his first lesson, and, the next day, to receive Mrs Lakhani’s adoring friends.

He made no attempt to discover London (which he’d, long ago, thought was interchangeable with England) all at once; he was fairly content to walk about Frognall Lane. Dressed in ash-grey trousers, a shirt and new shoes whose tightness he ignored, he walked down the slopes beneath the trees, staring patiently and affectionately at the children — they pretended not to notice him.

‘Don’t go too far, guruji,’ warned Mrs Lakhani.

From the sitting room, he’d look out through the French window into the garden when Mrs Lakhani had gone to work, leaving him with her daily, good-natured farewell, and he had nothing to do but reign absolutely over a house that was not his own; his complete possession of a place that in no way acknowledged him made him fleetingly nostalgic. ‘The pigeons are fatter here,’ he thought, watching the traffic of busy birds strutting on the grass. ‘And so are the sparrows.’ He’d presumed, previously, that the sparrows at home were universal in size and dimension. He now scrutinised these birds in the garden silently. It was his deceptive, inconclusive way of thinking, before Mrs Lakhani turned the key in the lock and opened the door, of where he’d come from.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.