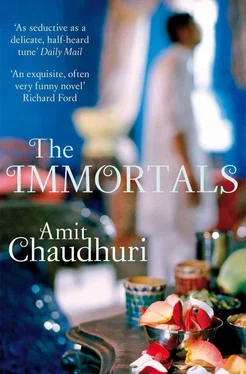

Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Amit Chaudhuri - The Immortals» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, Издательство: Picador USA, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Immortals

- Автор:

- Издательство:Picador USA

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Immortals: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Immortals»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Immortals — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Immortals», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

‘Shyam, I could listen to your bhajans for hours,’ said Hanuman Rao. ‘Once the film is released, this voice I love so much will be heard by everyone.’ Shyamji had been seduced, not just by Hanuman Rao, but by the magic of the colours — perennial, abiding always in a sort of springtime — of celluloid; the loss of its promise, and, with it, his money, had created a vacancy to which he hadn’t been able to reconcile himself, and brought a pressure to his heart.

No one mentioned Hanuman Rao’s name in that room in the nursing home.

* * *

‘SAAB, WE ARE in need of some money.’ That’s how Shyamji would broach the subject every few months with Apurva Sengupta. Very softly and decorously, not as if he were begging or asking, but sharing a piece of information that had been troubling him. The advance was ‘adjusted’ with the number of ‘turns’ taken teaching Mrs Sengupta; these English words, with their expeditious, dry clarity, had become part of the parlance. ‘Adjust ho jayega,’ said Shyamji, displaying the calm he never deviated from. ‘It’ll get adjusted.’

But this calm wasn’t only a pose he put on for the benefit of his students or family; it had become a dharma, a philosophy of life. It was partly a strategy of self-defence; he’d begun to suspect (but still didn’t wholly believe) that the world he was in love with — Cuffe Parade, Malabar Hill, the mirrored drawing rooms of his older students (plunged by marriage into affluence and anxiety), even the glamour of the film studios — was not quite going to, despite its extravagant, seemingly sincere, gestures of reciprocity, return his love: it had too many other things to do. The thought hadn’t formed itself in his head; but the detachment, the calm, had deepened a little.

‘Saab, what was the need for this?’ he said softly.

This time, money hadn’t been asked for; it had been offered; five thousand rupees in a stapled bundle had been placed discreetly by Mr Sengupta one evening in Sumati’s hands.

‘We are not rich,’ Mrs Sengupta reminded her husband. ‘In fact, we’re poor.’ Nirmalya heard his mother make this statement with a look of preordained, unshakeable conviction. It might be that she was berating herself and her husband for not having saved enough over the years; or just that she was reminding herself that the job, with its army of attendants and comforts, wasn’t forever. The servants themselves seemed blissfully unaware of the fact; symbols of continuity and wealth, they, despite their little quarrels, had the fixity and absence of care that symbols have; Mrs Sengupta almost envied them their strange abandon.

No, the scandalous remark had a context; it wasn’t meant for public consumption, but was a private release, like a curse or a prayer; now, in the early eighties, directors and executives had the satisfaction (as once their English predecessors had) of leading lives that had all the marks of affluence, and a prestige that traders and businessmen lacked: but their salaries were heavily taxed. Most of what constituted the lifestyle belonged to the company; most of the salary belonged to the government of India; and what was theirs (the pay that reached their pockets) was a relatively modest residue. At least that’s how Mrs Sengupta saw it. So she went through the motions and performed the functions of a company housewife and of being the chief executive’s wife, and, at the same time, cultivated the detachment of a sanyasinni, an anchorite — even when she was buying a Baluchari or wearing her jewellery — from this way of life. Or so she thought.

Those who seem to be rich feel compelled to behave like the rich. The money they’d given Shyamji, for instance, was given from real concern; they didn’t expect it back. But their generosity was complicated by superstition; Nirmalya, in spite of his heart murmur, had developed no symptoms, and they never forgot this fact. Someone was watching over him, and them, and their lives in Thacker Towers in Cuffe Parade; in the shopping arcade in the Oberoi; in the office and on the numerous social occasions that threaded the week — watching others too, possibly, but certainly them. In the midst of everything, they — mainly because of Nirmalya — were sometimes aware of being watched. The lifestyle became partly an enactment; they never quite experienced the luxury, the longed-for benediction, of being able to think it was all there was.

* * *

GRADUALLY, SHYAMJI got better. He felt the need to go back to the world, to embrace it, to win it over, to enjoy it — the old desire and restlessness returned. But it was preempted by his family’s optimism and impatience; almost as soon as they sensed Shyamji was recovering, they began to make plans for the future. The discontinuity and disjunction Shyamji’s illness represented was already a thing of the past.

Some of his students were emigrants. Mainly women, they’d lived for years in England; every winter, sometimes earlier, they’d come back, vaguely doubtful about returning, and at the same time questing, eager with expectation, to Bombay, their husbands following them like mascots. And here, for a month, for two months, they’d fold their cardigans and put them aside in a drawer; they’d stop wearing socks beneath their saris. They should have had a sophisticated and superior air, but they didn’t; living in suburban London and its environs made them feel provincial in the whirl of Bombay. Tooting, Clapham, and Surrey were where they lived; one or two lived in Hampstead; in their dowdy saris, they bore no signs of Englishness except an apologetic tentativeness. Now family surrounded them in the crowded flats they were staying in; this didi, that chachi, small, infirm mothers who continued to exist frugally from day to day, nephews and nieces they might have glimpsed as newborns, or not at all.

Music, besides family, is what drew them back — long ago, in the twilight before they left for England, when they were, most of them, newly married and unburdened with children, they used to sing, learn from a teacher. They didn’t sing well, but they didn’t sing badly; emigration, the hurried departure, the half-hearted, disbelieving resumption of their old life in a new locality and new weather, their mutation into the women they had become, had infinitely deferred their flowering as singers. Decades later, their children and their neighbours’ children grown up and ‘settled’, they felt they could resume from where they’d been cut off; their husbands had saved enough money by now to make that yearly journey to the nephews and nieces and the infirm mother. And, unexpectedly, one of the people at the end of that reverse journey was Shyamji.

‘You’ve been unwell, guruji. I hope you’re getting the right treatment,’ said Mrs Lakhani. She was more affluent than the others — she lived in Frognall Lane. She was unexceptional but reassuring to look at, in spite of the tired eyes and drawn face; years of rearing children, of listening to the silence, of rainy days, of socialising with other Indians, had left her just enough time to satisfy her weakness for music without giving up her friendships. Now, back in this difficult but unforgettable country, she sat, head bowed, as Shyamji, slightly recovered, sat on the bed, having donned a white kurta, and taught her a composition in raga Hansdhwani:

pa ni sa, sa re ga pa ni sa

It was afternoon; not the right time for Hansdhwani. Still, in England, there was no right time at all. Evening and afternoon and morning there were much the same.

‘You need a change of air, guruji,’ said Mrs Lakhani, once she’d finished singing the notes with him in her soft, unpractised voice, her uncertain tone and his, sweet but undemonstrative after the illness, in unison for a few minutes. ‘The air over there is very good. Not like here. Even pigeons are fatter there.’ She smiled at his restrained incredulity. ‘Come and stay with us. Come and stay with us over there. I will arrange some concerts, I will arrange everything. My friends are dying to listen to you.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Immortals»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Immortals» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Immortals» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.